On January 9 of this year, Roy Tarpley, the former NBA big man who played six seasons for the Dallas Mavericks, passed away at the age of 50. Tarpley had issues with drugs and alcohol throughout his career, as he was booted from the League in 1991 for the drug use, and then again in 1995 for alcohol use after a 1994 reinstatement. But he wasn’t the only one with substance abuse problems. In fact, the 1986 Draft alone was full of cautionary tales.

Of course, there’s the story of Len Bias, a guy who was presumed to be the NBA’s next big star, who could have battled Michael Jordan as the League’s best for years to come. But that never happened. Bias passed away two days after being drafted by the Boston Celtics in 1986 due to a cocaine overdose. Then there was William Bedford, the sixth overall selection by the Phoenix Suns, who had admitted to using drugs as a Detroit Piston and spent a year in rehab. The results of Bedford’s drug use were three arrests for possession, the latter which landed him 10 years in prison. Chris Washburn too, had his major troubles. Wasburn played just two seasons in the League, as three failed drug tests ended his career. He would also land in jail.

The profound sadness of the person ruined by drugs and/or alcohol is one of life’s ultimate tragedies. Not just professional athletes or those in the limelight, but any human being. The loss of life, as in Bias’ case, takes it to a whole new level of sadness. There are, however, the success stories. The ones who go through the same rough times, hit the bottom, and eventually turn their lives around.

Micheal Ray Richardson is no more special than Tarpley, Bias, Bedford, or Washburn or any other athlete who couldn’t curb their drug habit to save their career. Richardson, with his own cocaine troubles, could have ended up just like Tarpley. He could have been that sad story. With him, it could have even been earlier. Thirty years old, maybe he doesn’t even make it to 40. Who knew with Micheal Ray?

His most famous quote about the plight of his Knicks in 1981-82—“The ship be sinkin’”—ironically could have applied to his very own life. But some way, he got out. He was able to remove himself from the drugs, the dangerous life course that plagued him in his prime NBA years.

And so here’s Micheal Ray Richardson, the fourth overall selection in the 1978 NBA Draft, standing at the three-point line at the elbow extended of the gym of the YMCA in London, Ontario, Canada—where’s he’s been coaching the last two years. He shot the ball off of one leg, the ball in perfect flight, banking off the square of the backboard. Doing it again, nets the same result. He’d been shooting around for the last couple minutes, I myself would call it fooling. Never shy of playfully boasting, Richardson turned to his players seated backs to the wall and proclaims, “Ooh, I’m hot now.” This is Richardson’s fun before it’s time for him and his team to “go to work.”

It’s around 10 a.m., before the start of practice for his team—the London Lightning—reigning champions of the two-year-old National Basketball League of Canada. It’s 2013, and later that spring, Richardson’s team would bring home its second straight championship, finishing off a campaign that was nothing short of dominant—33 wins in a 40-game schedule, number one defense in the league, number two offense, leading the league in 11 statistical categories. His Lightning were the definition of quintessential team basketball—not one player exceeding 15 points per game, and nine players averaging double figures.

He doesn’t believe in one-on-one basketball. “Basketball is a team game” was his daily mantra, “basketball is a thinking game” his daily heed to his players. They both are part warning-part preparation tools to his players—if you want to make it in the NBA, you have to have the know-how. “His players” were a mix of young guys trying to make it in the game, fresh out of college and yearning for a chance at the big time, and veterans, guys who have been around in minor league basketball for a long time, true professionals.

One member, Rodney Buford, a former second round pick of the Miami Heat in 1999 who played on the first two Lightning title teams in 2012 and 2013. For the younger guys, Richardson was constantly in their ear, drilling home the “thinking man’s game” point, advising them on what to do, being firm while at the same time being every bit the teacher. His players are all ears to him when he speaks, and for good reason. After all, it’s not every day you get to learn from a former NBA All-Star.

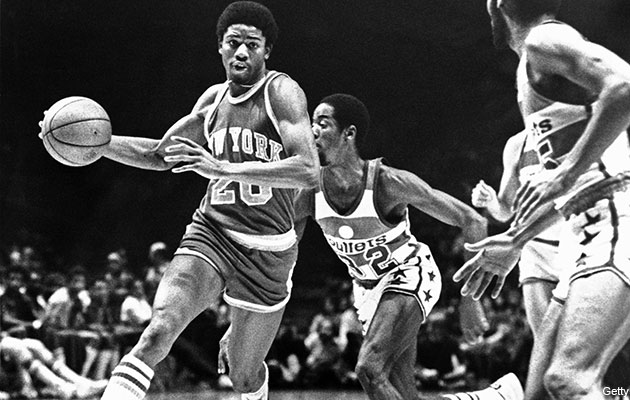

Once upon time, Micheal Ray was known simply as “Sugar.” He was 6 feet 5 inches, and roughly 190 pounds of ill skill. Magic Johnson-like passing, danger in the open floor, at-will scoring, and lockdown, don’t-you-pass-this-ball-in-my-lane-because-I’m-taking-it-the-other-way defense. He could shoot the three. He could post you up. He could go by you and score with a flashy layup. Whatever and however the way, Richardson could flat out ball. Four All-Star teams, two All-Defensive First-Teams, and the first and still the only to lead the NBA in assists and steals in the same season, 10.1 and 3.2 in 1979-80 at the age of 24.

He and Magic Johnson’s combinations of size and skills were the de-facto bridge between the standard point guard of the former NBA and the hybrids of today. In New York and New Jersey, Sugar was a star. But then began his downfall. His last NBA years were marred by stints in and out of rehab to fix a cocaine habit, beginning with what he has admitted was his tenure in Golden State as a Warrior, where he was traded to for Bernard King during the 1982-83 season.

King, of course, would revitalize the Knicks, a stone cold scorer who famously dropped 60 at the Garden on Christmas Day 1984 against Sugar and the Nets. Richardson, on the other hand, fell. He fell hard, hit rock bottom. The back and forth from rehab to the court never ended, and resulted in a permanent ban from the League in 1986, dashing the hopes of what would have been a Hall of Fame career.

Richardson now, 59, a little heavier around the waistline, a tad droopier in the face, is drug free. And from 2011-2014, he was coaching in London. He made a new name for himself as the marquee, most well-known, and best coach in an upstart Canadian League. He wasn’t known as Sugar, but “Micheal” or “Coach”. He did public appearances, was a guest on radio shows, and was active in the community along with the team.

Coaching in Canada, for and in a city of 350,000 people just two hours from where the NBA’s Raptors make their home, Micheal Ray Richardson was a figurative world away from where he was back in the 1980s. If you had asked him as a 24-year-old, where he’d be in 30 years, the last place on his mind I’m sure, would have been in the United States’ northern neighbor coaching minor league basketball. He would have never had thought it.

But here Richardson was, still dominant, just not on the court. His arsenal of skills were no longer blazing speed, stealth-like defense, or a cool jump shot, but skills consisting of a whiteboard, a dry erase marker, and his mind. A mind that had been continuously ripened with basketball knowledge all of Richardson’s adult life, one sharpened by the coaching of Hall of Famers Red Holzman, Hubie Brown, and a soon to be one in Larry Brown.

Richardson’s mind was also finely tuned by 14 years playing overseas, and finally capped by the last decade he’s spent coaching. Richardson was comfortable in London, Ontario, doing what he loved in a hockey hotbed where basketball was an afterthought before the Lightning came into existence and he was named coach.

When he would appear at hockey games for the city’s successful Ontario Hockey League team, more people wouldn’t recognize him than those that did. Did they know that he was a four time All-Star? That he was a flat out stud? That there are highlights of him clean-swiping Jordan, the Doctor, and Bird? No. But maybe that was a good thing. It allowed for Richardson to create a different legacy, a different mark on a different city than the vibrant, bright lights of Manhattan where he began his NBA career.

He wasn’t doing this for the money, he had said, rather because, in his own words, “I’d go crazy.” Maybe that’s true, but there’s no denying that a strong love for the game of basketball had gotten him to this point —the kind of love that drives you to stay involved with the game until you’re on the brink of 60.

“Find the Good.” “Be the Good.”

These sayings are on the rubber bands that adorn Richardson’s wrist. Over the years, finding the good and being the good have been his challenge, what he’s been striving for, what he’s been about achieving. Unlike some former athletes who have fallen on hard times without the rush of the crowd—failing to find that one thing to fill the gap left by the success, fan admiration and worldwide recognition that being a professional athlete may bring—he’s done something positive with his post-playing career.

He’d prefer to be in the NBA with a coaching gig, but that’s not where his life led him, at least to this point. Credibility is what he brought to another minor league, the former NBA All-Star with the type of suits and gator skin shoes no one around here had seen before. He was the city’s face of basketball.

Now, Richardson is gone from London and the National Basketball League of Canada. No more sideline animation, joking with officials, no more juggernaut teams to lead. A “mutual agreement” between himself and management ended his impressive three-year run as coach of the Lightning in June, in what he has recently said will be his last coaching stop. A 101-42 record, with two championships and one win shy of another trip to the Finals in 2014.

It’s evident now that Richardson has found peace in his life. He’s the type of guy people would assume things about, like all the judgments people reach for nowadays regarding people whom they don’t know, but have just heard bad things, or one specific thing, about. With Micheal Ray Richardson, it was always “that guy who got banned from the NBA for drugs.” But there’s more to Micheal Ray than that, aside from the fact that he was one heck of a basketball player. His daughter is a doctor, his kids overseas are doing well. He’s a brother, son, grandfather, just like anyone else. He speaks two languages. You see, things like these are the things that people don’t know, but need to know to understand what he has become, how far he has come as a person.

Over the years, he’s remained close with former commissioner David Stern, and credits Stern for giving him the realization – through banning Richardson from the league – that he had to change. Some guys kick the habit, and some guys just can’t. Richardson did. New York City, Oakland, and New Jersey were the toughest for him, the best times on the court but the toughest times off it. For a guy who averaged 20, 8 and 6 in his prime years, his toughest opponent was probably away from the basketball court.

He had a chance to return to the NBA with the 76ers in the late ‘80s, but conflicting views on a contract prevented it. So Sugar, after dabbling in the CBA with Albany’s Patroons (where he played with current NBA coaches Rick Carlisle and Scott Brooks) went to Europe. The years there—between Italy, Croatia, France—and Denver (as a Nuggets’ team ambassador), then to back to the CBA coaching in Albany and Lawton, Oklahoma, and finally, to Canada, were Sugar’s times to erase the dark past, the years of pain, of having dreams crushed. And in his quest to do so, he succeeded. So, would he change any of it? No, he says. Everything he’s been through has made him who he is today.

Richardson never won an NBA Championship. Never made it to the Naismith Hall of Fame. The NBA Store doesn’t sell versions of his jerseys. He isn’t in front office, ownership, or coaching positions like contemporaries Larry Bird, Magic Johnson or Kevin McHale. Never received NBA head coaching jobs like his Knick teammates Bill Cartwright and Mike Woodson. Instead, he played the game of basketball until he was middle aged, won numerous European championships, won more championships as a coach, in four different countries. He has taken his love of basketball everywhere he’s went, and it has saved him. As of now, he and former teammate Otis Birdsong lead youth basketball camps around the United States. They instill discipline, work ethic, and help youngsters develop the skills and love for the game that made them famous. He’s even taken up substitute teaching—in Oklahoma where he resides—in his spare time away from the game.

In some ways, it’s a miracle he’s made it this far. But having a second chance, the opportunity to turn his life around, Richardson did. He could have ended up like Tarpley. He could have been homeless on the streets like former NBAer Eric Williams is now, he could have been still an addict, have never recovered, never gone on to play basketball a day after February 24, 1986, the date of his last NBA game. The guy who fell just as hard as his NBA superstardom rose, made it back. A kid born in Texas, raised in Colorado, who went to college in Montana, drafted to a team from New York City, then across the country to California, then back to the East Coast to New Jersey, then Albany, and then three European countries, back to Colorado, back to Albany, and Oklahoma and Canada? And went through rehab numerous times a cocaine addict and was banned from the NBA? An improbable journey. But Richardson made it.

The Whatever Happened to Micheal Ray? documentary done by TNT in 2000 was the update on him at the time, the answer to the question of what had become of one of the NBA’s all-time super talents after a drug ban and a decade-plus overseas. Since that time, there has been continued growth in the man that is Micheal Ray, more successes, more defying the odds that were stacked so not in his favor at one point in time. In the fall of 2014, the MSG Network aired a special in their Beginnings series, about the life of Richardson—from where he started, to the present. The 30 minutes watched was well spent, Sugar in his own words, discussing his childhood, the love of his family, and the special bond he had with his mother. It was Micheal to the core. The summation of Richardson’s journey, perseverance as a man, can also be cleared up in a mere few words.

“Here I am. Still able to run full with all the drug problems I had. Crazy isn’t it?” That was direct from Richardson, relayed to former NBA columnist Peter Vecsey, about his current physical state, in comparison to other former players Richardson sees who have trouble walking and other physical ailments. For a guy like Micheal Ray, it is crazy indeed. At 59 going on 60, it is clear what he’s done with his life.

Micheal Ray Richardson’s ship is no longer sinking. He’s found the good.

Jake Carapella is a graduate of Western University and was a statistician and scout for the London Lightning of NBL Canada for three years. Follow him on Twitter @Jsports22.

Images via Getty