She’s been used to it all her life. It’s one of the things—one of the many, many things—that signifies her greatness. Whenever Chamique Holdsclaw steps on or near a basketball court, the challenges from the fellas start flying.

“What’s this girl doing here?” they questioned when she was 12, holding her own at the park in Astoria, Queens, after school and on the weekends.

“She ain’t really that nice that she can hang with us,” they mistakenly thought when she became a dominant force in high school.

“Let’s see if she’s still got it,” they wonder when they see her today, four years removed from her last game in the WNBA, and a decade and a half after forging an inimitable collegiate legacy.

So, yeah, she’s used to guys tossing that tough talk her way. And she’s used to proving why she was there, that she was that nice and that she’s still got it.

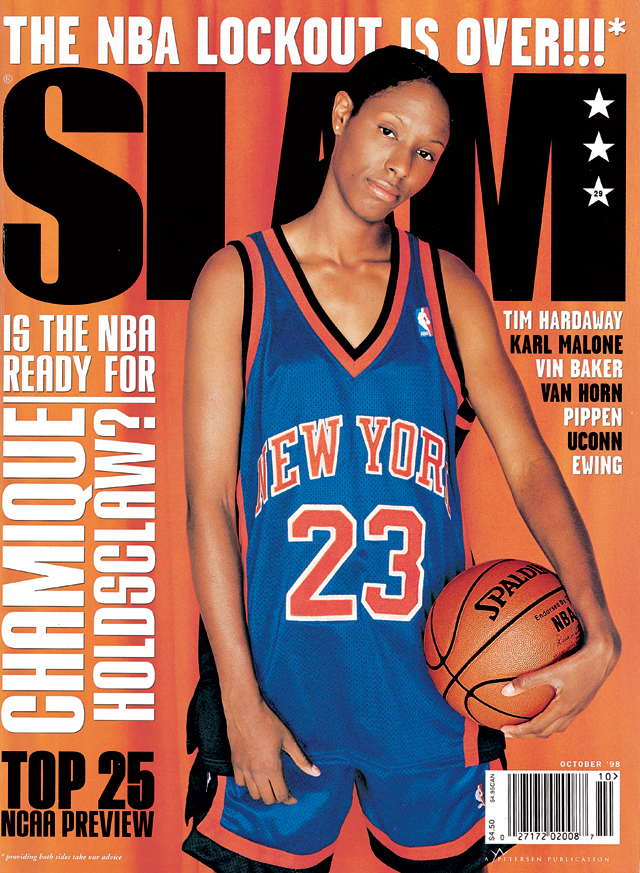

Of all the distinctions, honors and awards that Chamique Holdsclaw has amassed, there’s one in particular that’s our favorite—and seems to hold a special place in her own retrospect of her career, too.

It was late-summer, 1998, and Mique stood alone on the cover of SLAM. The first (and still only) female baller to get the honor. She stood front and center, exuding the confidence you’d expect from a college senior who had cut down the nets three years in a row and was being championed as potentially the best female hooper to ever lace up. Only, she wasn’t repping the Tennessee Lady Vols.

“We tried different things, and then I remember them breaking out the Knicks jersey,” she says, thinking back. “Next thing I know, it’s like, ‘Is the NBA ready for Chamique Holdsclaw?’ It was a statement piece: Women’s basketball had arrived.”

That’s exactly what the cover asked, and we weren’t the only ones. Sure, it was hyperbole in some ways, but what she had been doing since high school made for a debate that bordered on reasonable.

At Middle Village (NY) Christ the King, Mique won four state titles in a row. Though she didn’t play a ton her freshman year, that skinny teenager quickly went on to become the best player on the court every night—and in the entire country.

“There are great players, but very few have the same charisma of a Michael Jordan or Reggie Jackson,” her high school coach, Vincent Cannizzaro, told SLAM in ’98. “Their mere presence excited opposing fans. Young girls want to have a role model like that, a player they can emulate. They can’t pattern their game after Jordan, Patrick Ewing or Karl Malone. They can pattern it after Chamique Holdsclaw.”

In the fall of 1995, she stepped on campus at the University of Tennessee with a typical mixture of excitement and nerves that any college freshman feels. Unlike most, though, she had lofty expectations and a disciplinarian in coach Pat Summitt making sure she’d meet them.

“I felt like a fish out of water,” she says, reminiscing on that early transition from the bustling streets of New York to her new home in Knoxville. “And you have somebody always yelling at you, and you wonder, Do they really have my best interests?”

Despite the shock, rigid boundaries were nothing new for Mique, who spent much of her youth raised by her grandmother, June, as her parents dealt with alcohol issues. Once she settled in with her grandmother, home life became stable—and her support system was stronger than those of many of her peers around the projects. Homework before hooping. It was simple and effective.

The structure June provided was crucial in helping Mique become a student-athlete ready to land a DI scholarship. And when it came time to choose, it was her grandmother who urged Mique to become a part of Summitt’s program.

“She challenged me, and that’s when I realized we were a perfect match,” she says. “It was like my grandmother, almost. I never wanted to disappoint my grandmother. And that’s when I had to realize, [Coach Summitt] wants the best for me. She’s bringing something out of me I didn’t know that I had in myself.”

What did Summitt help Chamique bring out of herself?

Three straight National Titles, in 1996, ’97 and ’98, including a 39-0 season. SEC Player of the Year in ’97 and ’98. Naismith Player of the Year and Associated Press Player of the Year in both ’98 and ’99. Naismith Player of the Century. One of 10 women to score 3,000 points in a collegiate career. Earning the nickname the “female Michael Jordan.”

Standing at a sturdy 6-2, Holdsclaw was dominant. She could score with seeming nonchalance from the perimeter or in the paint. She was a freak on the boards. She was a leader. She was a winner.

In ’97, a year before his squad would lose to the Lady Vols in the Tournament Final, Louisana Tech coach Leon Barmore called Mique, “maybe the best ever to play this game.”

Summitt concurred. “I think she’s the best,” she told Sports Illustrated in ’98. “I’ve said that all year.” She doubled down in ’99: “I think she’s that Jordan-type of player and person.”

It was only right, then, that one of the most storied college hoopers of all time became the first overall pick in the WNBA Draft in 1999. (A note on just how far ahead of the competition she was: the next 16 players drafted were either coming from overseas or the recently disbanded ABL; it wasn’t until the 18th pick that another woman fresh out of college was selected.)

Nabbed by the woebegone Washington Mystics—who went 3-27 the previous year—Chamique played her first season in what was just the league’s third. She quickly became not only the face of the franchise, but also one of the most prominent across the WNBA. Her picture was plastered on billboards in DC and she signed what was at the time Nike’s largest endorsement deal ever for a female.

“To see your dreams come into fruition was really powerful,” she says. “Unlike men, I didn’t go to college saying I was gonna play professional basketball [in the United States].”

Along with the thrill of this new reality came pressure and change: some, the same pressures any kid deals with when they’re first out on their own; some, far greater. “I was 21 years old and I didn’t have my grandmother, I didn’t have Coach Summitt,” Mique recalls. “It was kinda tough because we would have two-a-day practices, two hour and 30 minutes, and then you gotta play back-to-back games, and you’re traveling. Everybody may not be as unified because it’s women of all ages and personalities.”

The team got marginally better that year, going 12-20, largely behind Mique and her averages of 17 and 8. They also led the league in home attendance—something they’d do multiple times during Holdsclaw’s career.

The squad steadily improved over the next couple seasons, and their centerpiece was becoming a star of the pros like she had been in college and high school. In 2002, things seemed like they were finally fully clicking: She led the league in both scoring and rebounding with averages of 20 and 12, and the team posted a 17-15 record, good for a 3-seed in the playoffs.

But all was not right. Early in the season, Chamique lost her grandmother. “That really effed me up,” she says. “I put this wall up. It was almost an out-of-body experience. This is the person I went to for everything. This is the person that technically saved me. She nurtured this broken kid. I lost my world for a second.”

Suddenly, feelings that had been bottled up began creeping to the surface—but still remained mostly suppressed. “I started having issues with severe depression,” she admits. “I kept everything hidden. When you keep things under the rug, sooner or later they come out, and they come out raging. And that’s what happened.”

During the ’04 season, she missed a game in July against the Charlotte Sting. Dealing with that inner struggle, she stayed locked in a townhouse and refused to come out. She’d soon take a leave from the team for what she described at the time in a statement as “deeply personal” reasons. Following the ’04 campaign, she requested a trade and was sent to the Los Angeles Sparks.

But a change in scenery didn’t fix the problem, it was merely another way to not fully confront it. Until she had to.

In 2006, she woke up in a hospital, having overdosed on medication she had been prescribed for her clinical depression. It was a suicide attempt.

“That’s when I was like, Enough is enough,” she says. “I have to take care of me.”

And that’s exactly what she did. Slowly, she began to speak out about her mental illness. For the first time, she was owning what she was going through.

“I was like, I’m not embarrassed anymore,” she says. “I have an illness. I have something wrong, and I have to take care of this. I know how I feel. People don’t know how I feel. People see the outward appearance. The smile. But they didn’t know what I was feeling inside.”

Just games into the 2007 season, she announced her retirement.

Despite six All-Star appearances and some gaudy stats, Mique didn’t have the pro career that she and most others thought she would. Still, she played over a decade in the league (she came back in ’09 and ’10 to suit up for the Atlanta Dream and San Antonio Silver Stars, respectively), in addition to stints overseas and winning Olympic Gold in 2000.

And now she’s working to make her time away from the court as impactful as her legacy on it. Working to help highlight not her career averages, but even more important numbers.

Like that 26.2 percent of adults in the US suffer from some sort of mental disorder in a given year. Or that one out of 20 people over 12 suffer from depression. Or that 5.7 million adults are affected by bipolar disorder in a given year, and the median onset age is 25 years old.

In 2012, she released an autobiography, Breaking Through: Beating the Odds Shot after Shot, which spoke openly about her mental health issues and shined a new light on them. That same year, she was diagnosed with Bipolar II disorder. In November 2012, she was arrested for aggravated assault after fighting with her girlfriend.

The incident was a personal and professional speed bump, but she didn’t let it slow her mission. If anything, it proved how real these mental health issues are and the constant struggle for those dealing with them.

Mique now makes regular speaking engagements and in early 2014 launched the Chamique Holdsclaw Foundation, which works to promote mental health education and understanding while stripping away the taboo associated with mental health issues—both within sports and society. She’s also participating in a documentary about her journey that has many of those same goals.

“As long as people can’t talk about it, then you can’t get people behind it to change the priorities [of public policy],” says Academy Award-nominated filmmaker Rick Goldsmith, who’s currently producing and directing that film, MIND/GAME: The Unquiet Journey of Chamique Holdsclaw. “There’s such a long way to go, and that’s one of the things that’s important about what she’s doing, because she’s high profile, and the more high profile people that can do that, the better.”

These days, when she’s at the gym, Chamique Holdsclaw still gets approached. And, of course, there are still those men who talk trash, like they have for more than two decades.

“But you always have that guy that will come by, and he’s almost shaken,” she says. “And he’ll be like, ‘I just wanna say, I saw your story’—this is a man with a deep voice, really low—‘I know all about it, I always respected you as a player, but I went through something serious, similar, and I just want you to know you’ve given me a lot of strength.’ That’s when I know God is using me in another way.”

It’s one of the reasons that she’s at peace.

“Something that I’ve struggled with, and that tore my life apart at times, to become a source of strength for people, to say that they can make it, that they can push through something, makes you feel like you’re hitting those game-winning shots.”