Had the trio of Charles “Chuck” Cooper, Earl “Big Cat” Lloyd and Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton come with scouting labels leading up to the 1950 NBA Draft, they’d have read simply: “Under extreme pressure.”

Cooper was the first African-American player to ever be drafted into the National Basketball Association, Lloyd was the first black player to ever play in an NBA game (Washington Capitols vs. Rochester Royals) and Clifton was the first black player to ever sign an NBA contract.

All three were landmark professional hoopers struggling for equal rights, acceptance and inclusion in a racially-charged America where tensions against minorities were at an all-time high. The three of them endured racist taunts and threats and often couldn’t stay in the same hotels (once in North Carolina, Cooper had to spend the night on the train), go to the same movie theaters or eat in the same restaurants as their teammates, especially on the road. But they persevered through it all.

“I remember in Fort Wayne, Ind., we stayed at a hotel where they let me sleep, but they wouldn’t let me eat,” said Lloyd. “Heck, I figured if they let me sleep there, I was at least halfway home.”

It was 1950—three years after Jackie Robinson had broken the color barrier in baseball, but 15 years before “Bloody Sunday,” when nearly 600 civil rights supporters marched across Edmund Pettus Bridge from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama for equal voting rights. Cooper, Lloyd and Clifton didn’t set out to change the world by being pioneers in the annals of Black History—they just resolved themselves to chasing basketball dreams and playing the game they loved at the highest level.

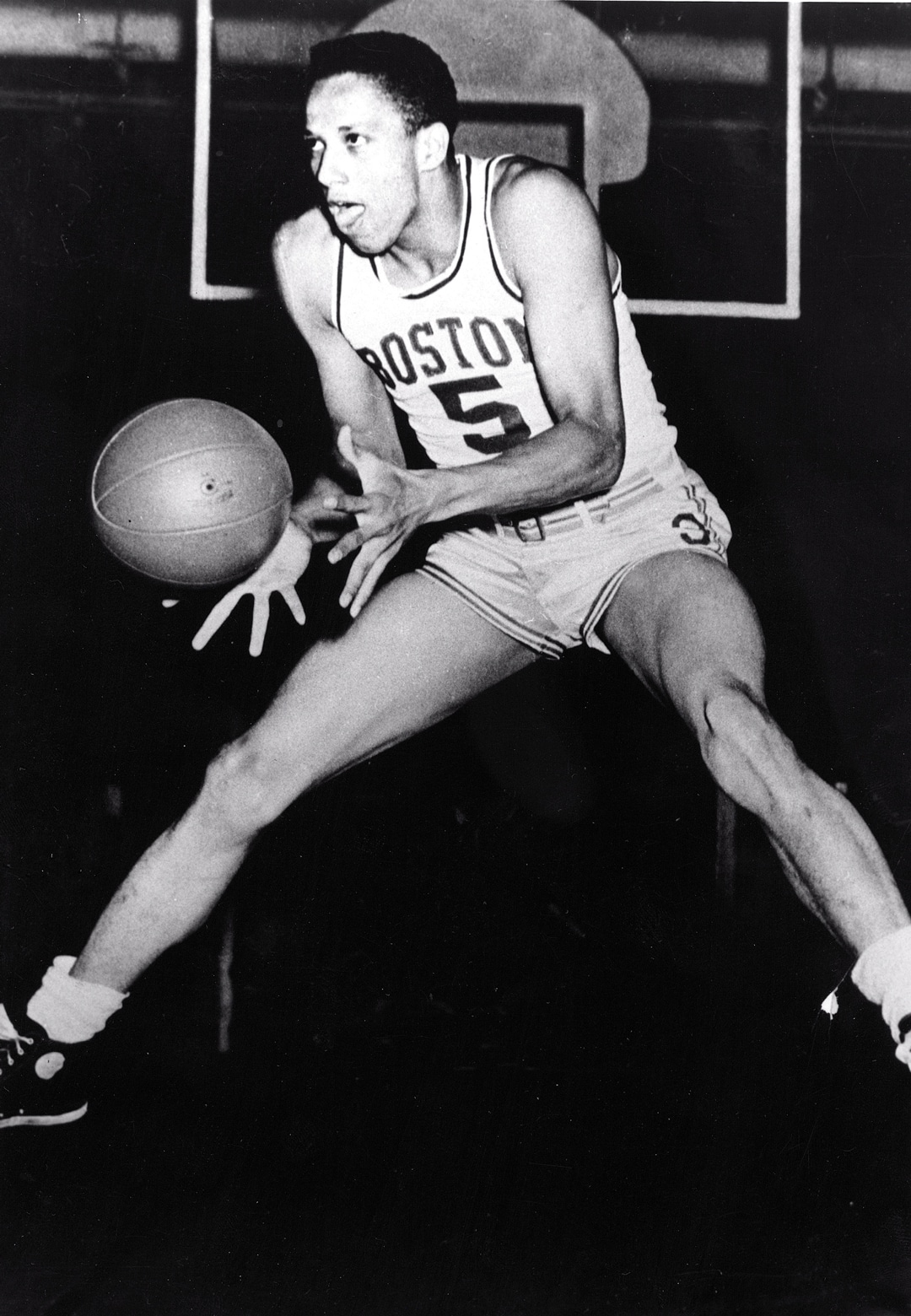

Following a brief stint with the Harlem Globetrotters after graduating from Duquesne University, where he was an All-American, Cooper was selected 14th overall by the Boston Celtics. According to The Boston Globe, when Celtics owner Walter Brown was reminded that Cooper was black, he reportedly said, “I don’t care if he’s striped, plaid or polka dot!”

Cooper averaged 9.6 points and 8.5 rebounds in his rookie season under head coach Red Auerbach and was able to fend off the race-baiting hostilities against him partially by attending jazz concerts with fellow rookie and teammate Bob Cousy.

The 6-5, 210-pound forward spent four years with Boston before ending his career with the Milwaukee Bucks and the Fort Wayne Pistons.

Lloyd, who was drafted by the Capitols in the ninth round (100th overall), scored six points and pulled down a game-high 10 rebounds in his NBA debut, a 70-78 loss to the Royals. The 6-6 defensive-minded forward believed that he was given a chance to be the first black player to hit the court in the League because the Celtics had drafted Cooper with such a high pick.

“If the Celtics did not draft Chuck in the second round, you could not tell me that the Washington Capitols in 1950 were going to make me the first black player to play in this league,” Lloyd told The Boston Globe. “No way…The Boston Celtics had a tremendous influence on my acceptance in the NBA.”

The Capitols folded in 1951, so the Syracuse Nationals picked Lloyd up off waivers before he spent the 1951-52 season fighting in the Korean War. The U.S. Army veteran then played six years for the Nationals, winning a title in 1955, and two for the Detroit Pistons.

Once his playing career was over, Lloyd went on to become the first black head coach of the Pistons in 1971 after paying his dues as an assistant and scout. He died in 2015 at the age of 86.

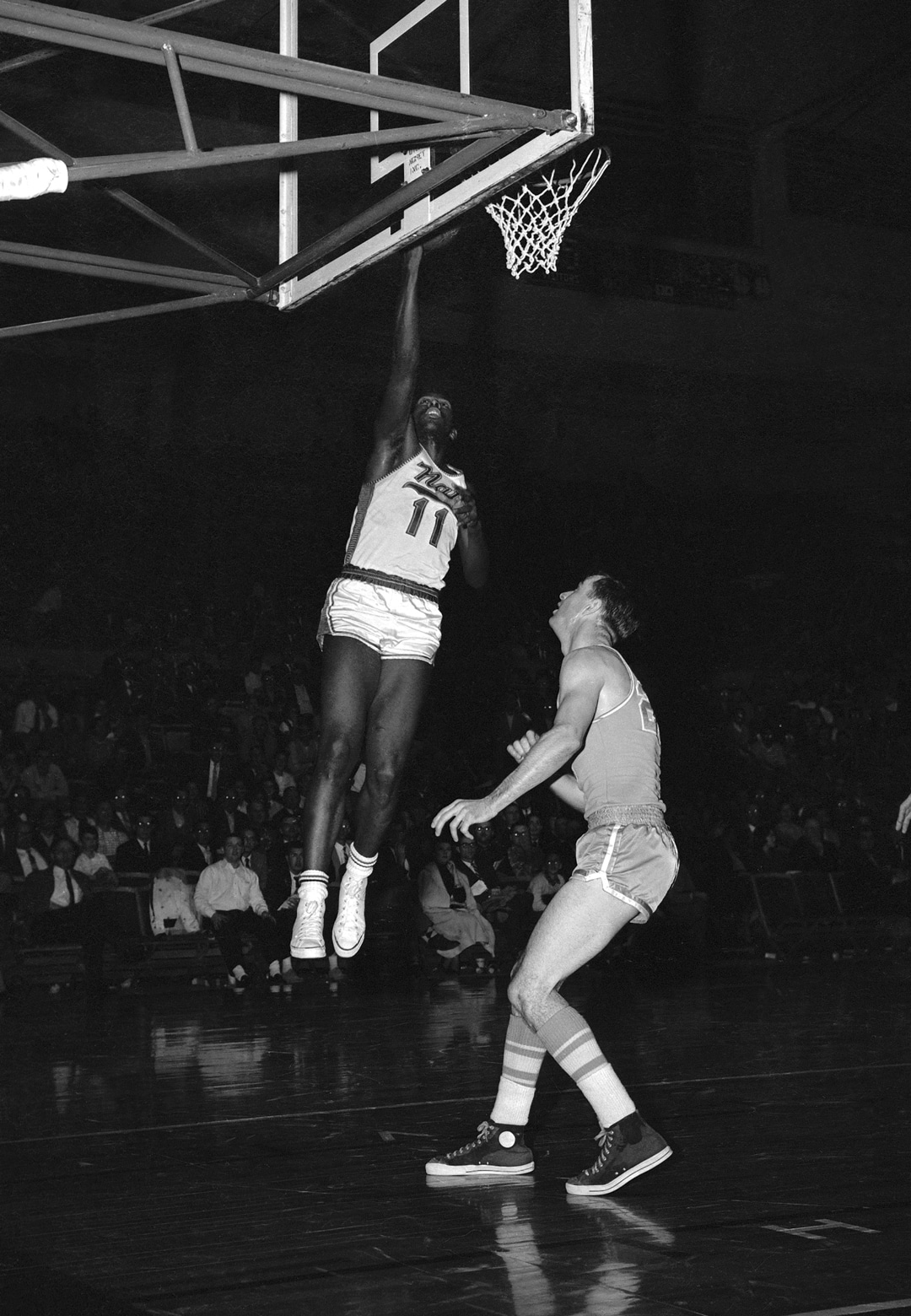

Renowned as a multi-sport athlete, Clifton played baseball (first base) for the Chicago American Giants of the Negro American League and basketball for the Globetrotters and the New York Renaissance before signing his barrier-breaking contract with the New York Knickerbockers in 1950.

As a 27-year old rookie center, “Sweetwater” helped the Knicks make it to the NBA Finals, where they lost to Rochester in a seven-game series. Clifton averaged 10 points and 8.2 rebounds over eight years in the NBA (seven with New York, one with Detroit) and defied father time by getting his first All-Star nod as a 34-year-old in 1957. He passed away in 1990.

Both Clifton and Lloyd were later enshrined in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, but Cooper, who died at age 57 due to cancer, has yet to receive the nod.

“It would be a tremendous honor,” Chuck Cooper Jr. told ESPN. “He was proud of becoming the first African-American drafted. I can only imagine how proud and honored he would be to be elected to be in the Hall of Fame.”

Accolades aside, it’s vital that these three integrationists are properly appreciated for changing the course of history and blazing a trail for early black NBA players like Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain and Oscar Robertson and so many of the league’s current superstars.

“There’s so many different guys who paved the way for where we are now, so many different guys in our league and we’re so grateful for them,” nine-time All-Star Chris Paul said of Cooper, Lloyd and Clifton. “Not just during Black History Month, but I think every month. All year round, we need to be grateful and thankful to those that paved the way.”

—

Maurice Bobb is a contributor to SLAM. Follow him on Twitter @ReeseReport.

Photos via Getty.