In SLAM 210 (still on sale!) we chronicled one important old school player from each of the past four decades. For the 2000s, we picked Larry Hughes, who is now a family man after a 14-year career. —Ed.

—

There are days when Larry Hughes still needs to hear his baby brother’s voice. December 18 is one of them–that was Justin’s birthday. January 3—that’s the day in 1996 that Justin, at age 10, received his heart transplant, a procedure that was supposed to save him from the heart defect he was born with. Also, May 11—that’s the day Justin, at 20, took his last breath. His body eventually rejected the heart.

Eleven years have passed since then, 11 years since Larry last felt the warmth of Justin’s embrace. He still has the tattoos of two teardrops underneath his left eye—a constant reminder of what he lost. But on the days where he misses him more, Larry will take out his cell phone and dial his baby brother. He’ll let it ring and ring until his brother’s voice—the voicemail greeting—hits his ear.

“I still pay his phone bill—I never turned it off on purpose,” Hughes says. “I’ve been able to heal and grieve and am at peace with it, but some days you can’t let go.”

And so instead he does his best to live the life he thinks his brother would have wanted him to. Cliché? Perhaps. But the 38-year-old Hughes, five years removed from his last NBA game, says family is what his time revolves around now.

Take a drive on a school morning through St. Louis, where Hughes grew up and now resides, and perhaps you’ll spot the former first-round pick and 20-ppg scorer, shuttling his two youngest children to school. Afternoons are often spent cramming his skinny 6-5 frame into a chair to watch his daughter’s dance recital. On fall weekends Hughes and his wife will pile all four kids—and whatever cousins happen to be around—into the back of the black sprinter van they own and take a field trip to the local pumpkin patch.

“I go to everything, man—my schedule revolves around the kids,” Hughes says. “One of the reasons I stopped playing professional basketball is because I wanted to be around them. That’s my motivation.”

Of course, it’s not like Hughes has left basketball behind. He runs a youth basketball academy, and is one of many former NBA players suiting up for Ice Cube’s 3-on-3 league, BIG3.

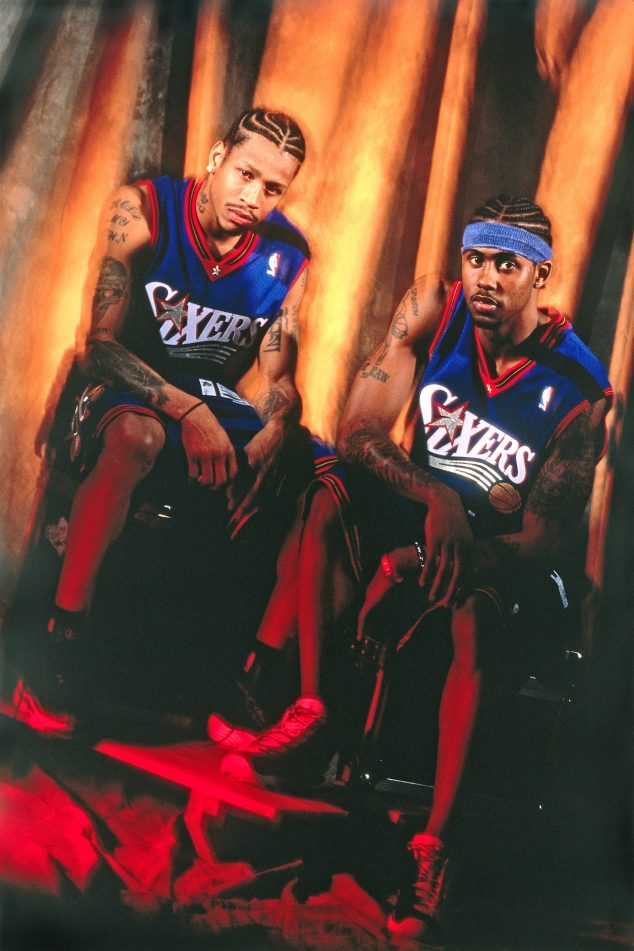

In fact, Hughes still thinks about his NBA career, about his 2007 Cavs team that made it to the Finals—on the back of some epic performances from a young LeBron James—just days after Justin had passed. He thinks about his time with the Sixers, alongside good friend Allen Iverson, and his days with the Wizards, where he put up the best numbers of his career.

“I’ve been around a lot, I’ve seen a lot,” he says. “From a sports standpoint, from a life standpoint, it’s fun for me to be able to try to relate and help the kids I work with.”

But what about those who say that someone like Hughes, a player who at times received the dreaded label of headcase or bust, might not be the best role model for aspiring stars?

“Yeah, anytime you’re misjudged, it’s going to bother you,” Hughes adds. “For me, it’s just about how you form these opinions. If it’s because we had a conversation and that’s what you think about me, then fine. But if you just look at me, and see cornrows and tattoos, shit, that can get frustrating.”

Let’s pause for one second, though, because this is an anecdote that should be noted. You see the curse word in that previous sentence? Well, according to Jared Jeffries, who played with Hughes in Washington, a love of that synonym for defecation just happens to be Hughes’ most endearing trait.

“Larry’s always saying, ‘sheeet,’ with a drawl, and it’s like the ‘I am Groot’ line from Guardians of the Galaxy,” Jeffries says. “It can mean so many different things—he could be happy, angry, sad. It all depends on the tone.”

In the case of this interview, the meaning of the word is clear. Hughes is tired of being misjudged by strangers, yet also comfortable enough in his own skin to pay these insults little heed. At this point in his life there are more important things for him to worry about. He’s got a household full of kids to shuttle around and a gym full of players to teach.

There’s a brother’s memory to honor.

Perhaps even a voicemail to leave.

—

Yaron Weitzman is a Senior Writer for SLAM. Follow him on Twitter @YaronWeitzman.

Photos via Getty Images