The Earl Monroe New Renaissance Basketball School is Preparing Students For Careers Around the Game

On the first day of basketball tryouts, half of the school showed up. Kenneth Miller, the boys coach, assessed the assembled crowd of 50 freshmen. Some of the 13-to-15-year-olds in front of him looked old enough to vote. Others didn’t look tall enough to ride a roller coaster. Some were in fresh, new Nikes with their laces pulled tight. Others were wearing mismatched socks and baggy hand-me-downs. But Miller knew that they were bound by their shared obsession with basketball, and he sensed his first opportunity to bring his new school’s mission to life.

As the tryouts progressed, Miller started scouting not just for players who could sink a pull-up jumper from the elbow or who could put a defender on his heels with a crossover, but also for the kids who offered up a hand to someone who had hit the deck or who encouraged a classmate to grab some water between drills. He wanted to identify not only the teens who would round out the roster, but also those who would support the team without ever wearing a uniform. That, after all, was the design of the Earl Monroe New Renaissance Basketball School.

“Not everyone could make the basketball team, but everyone could be an important part of the community we’re building,” Miller says. “That’s why we asked some kids who didn’t make the cut to be managers or run the scoreboard or take pictures. Those opportunities can be life-changing, too.”

For the 110 freshmen who signed up to be a part of this inaugural class, Earl Monroe New Renaissance Basketball School was an opportunity to prepare for a career around the game of basketball. Founded by filmmaker Dan Klores, who directed Reggie Miller’s 30 for 30 and Basketball: A Love Story, the program is an antidote to the myriad prep schools that have proliferated in the past two decades.

Earl Monroe is a public charter school only available to students in New York City. Its inaugural class will expand to a total student body of 440 during the next four years, and the students will have the chance to “major” in fields that support the sport—like media, marketing, analytics, law and health care. In other words, in a world awash with basketball schools, Earl Monroe is a basketball school.

“You probably won’t see any of our kids on the cover of SLAM,” Klores says. “But they’ll be in the background, helping to support the next generation of Hall of Famers.”

The door to James Ennis’ classroom is emblazoned with the Portland Trail Blazers logo. Around Earl Monroe’s campus, which is housed in a former Roman Catholic school in the Bronx while a $25 million facility is being built, all the rooms are named after NBA teams. (There are no rooms named after either of New York’s teams, though, to avoid the endless debates.) And Ennis takes his team connection seriously. On a Wednesday morning in early December, the 29-year-old teacher, who was wearing a ribbed tan turtleneck beneath a fitted blue suit, began a PowerPoint lesson about résumés with a quote from Portland superstar Damian Lillard: “To look good in front of thousands, you must outwork thousands in front of nobody.”

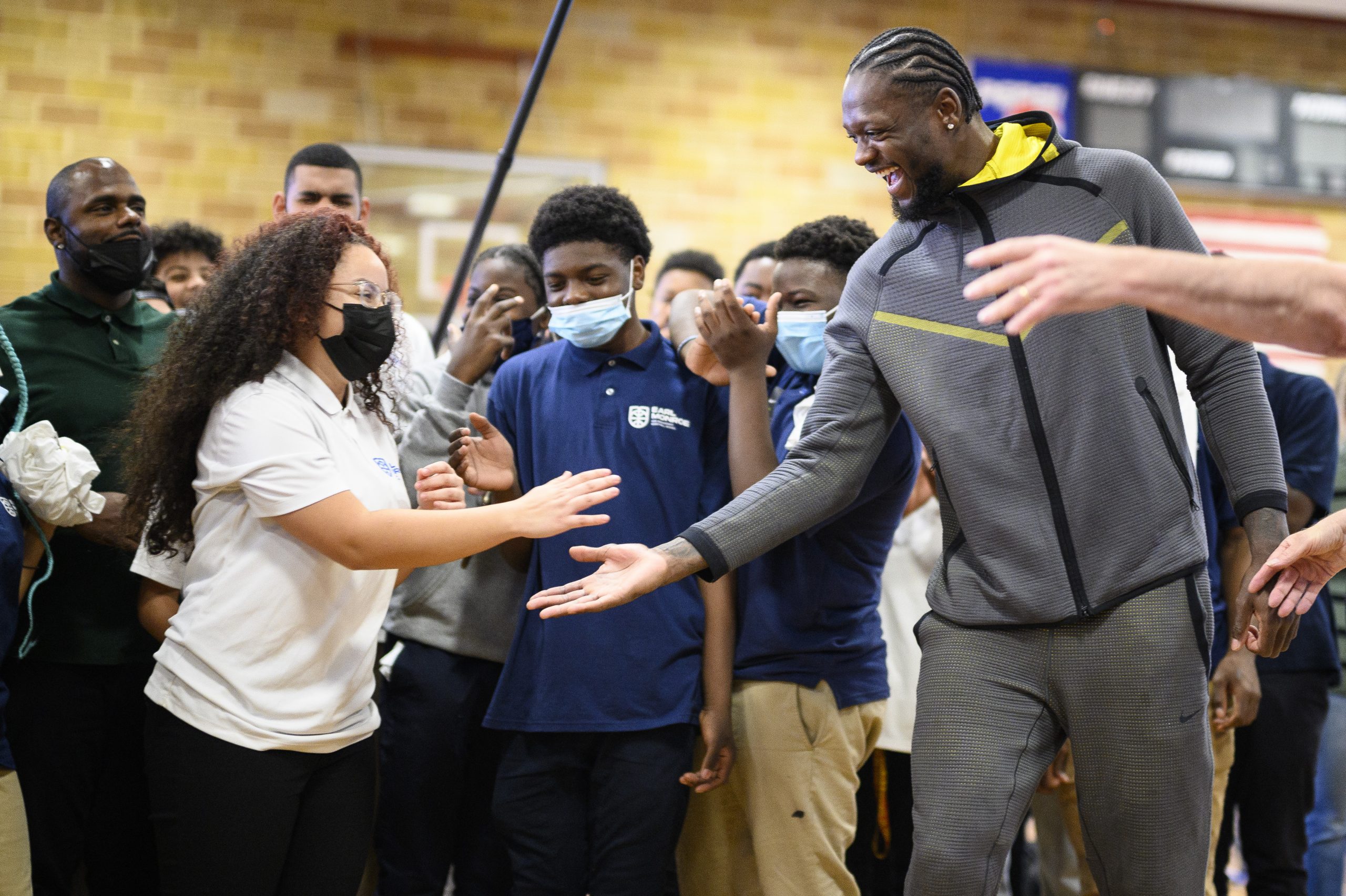

The school’s existence is a testament to the work Klores was willing to put in while no one was watching. Klores, who also founded the prestigious NY Renaissance (aka the “Rens”) EYBL program, first came up with the concept eight years ago. He slowly built a board of advisors that included former NBA Commissioner David Stern and Knicks legend Earl “The Pearl” Monroe, after whom the school takes its name. And he managed to raise nearly $5 million from the likes of Nike and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The school officially launched during a ceremony in October, which was attended by NBA commissioner Adam Silver and NBPA executive director Michele Roberts, who are both native New Yorkers. “For every NBA player,” Silver told the students, “there’s 100 related jobs in the NBA and its teams.”

Ennis teaches Foundations of Basketball, which is designed to introduce students to those jobs. For now, it’s the only course that focuses on the game. Classes on specific subjects like broadcast journalism and coaching will come later, as students become upperclassmen. Right now, Earl Monroe’s educators are focused on foundations of education for their pupils. Although Earl Monroe—like all public schools in New York City—is open to any student from the five boroughs, a disproportionate number of kids are from the Bronx. The borough has been disproportionately impacted by the coronavirus pandemic. Many of the students at Earl Monroe have not attended in-person school full-time since they were in the seventh grade. And during the two years of remote learning, many struggled with connectivity, because they were on unreliable devices or unstable internet connections.

“Not everyone was connected to learning equally during the pandemic,” says Kern Mojica, the school’s principal. “We’re focused on the core classes that all students need first, and then we’ll branch out into niche areas of interest. But we make an effort to infuse basketball into every aspect of the curriculum.”

When Mojica was in the classroom as a teacher early in his career, he tried to infuse sports into every subject. He’d use Stephen Curry’s shooting to talk about parabolas, or Super Bowl start times to discuss distributions. A former defensive lineman at the University of New Hampshire, Mojica connected to the vision of Earl Monroe straight away.

“The odds of making it to the NBA are about the same as winning the Powerball,” he said. “We wanted to provide our kids with other possibilities for the future—with other dreams. For us, a student going pro means that they work in a law firm, or the League office or TNT.”

In class, Ennis explained how a strong résumé could help the students get any job they want, from summer employment in the city to their dream gig at Nike. A boy in the back raised his hand and asked, “Why do I need a résumé? I want to be a streamer on, like, Twitch and YouTube, and you don’t need a résumé for that.”

“That’s a great question,” Ennis said. “You still need a résumé because that’s how you build partnerships and attract sponsors. That’s how you make money.”

Ennis then broke the classroom up into small groups. The school provids all students with Chromebooks, and they wrote their résumés on a Google Docs template that he designed. As the students worked, Ennis and Mojica checked in with each group, asking them about what jobs they could see themselves in long-term. One student named Alvin told Mojica, “I thought I was gonna be an NBA player, but I didn’t make the basketball team.” Mojica nodded, as

Alvin continued. “So I’ve been thinking about some other stuff instead.” He wrote on his résumé that he wanted to be a broadcaster.

Before dismissing the class, Ennis reminded them that their podcasts were due next week. As part of their discussion of sports media, Ennis had them each come up with a concept for a show, design cover art for it, record an episode and upload it to Spotify. A student named Corey said that the podcast project has been his favorite thing he’s ever done in school. It’s called “The Greatest,” and it’s about the NBA GOAT debate. For the record, Corey is on Team Michael Jordan—even though he was born several years after MJ’s final game.

“People like to bring up stats,” he said, “but I don’t see it in stats. If you last 19 years in the NBA, I’d expect you to pass somebody. I look at it like, his mental greatness—MJ lost and came back and still won it. Plus, he’s still beating LeBron in chips right now.”

Ennis smiled brightly when he saw students so excited about their schoolwork. “That’s what separates our school,” he said. “A lot of public schools are still using a 1970s format in the sense that they’re preparing students for life in the 1990s. Our school is preparing kids for 2021 and beyond.”

Of course, there’s still plenty of actual basketball. If they have spare time between classes, students are allowed to go to the gym to shoot hoops. On the weekends, Kenneth Miller hosts an empowerment program that helps kids develop their skills—in basketball and in reading. And on a Thursday afternoon in December, a crowd of about 75 stuffed into the school’s small gymnasium to watch the boys team play The Cathedral School. Because of scheduling challenges, it was only the team’s second game of the season. And it wasn’t technically a game—it was a six-quarter scrimmage, with the score resetting after each period. But that didn’t bother the crowd, who were mostly students and who were raucous from the first whistle to the last.

Miller coached Earl Monroe to an easy win in every quarter. Meanwhile, on the sidelines, athletic director Andy Borman coached the managers on how to run a game. Borman, who is also the executive director of the Rens and the nephew of Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski, hovered over the scorer’s table, reminding the shot-clock operator to switch the possession arrow and the bookkeeper to mark turnovers. When a manager named Anthun abandoned the bench to say hi to some friends on the other side of the court, Borman tracked him down and pulled him into a tight, friendly hug. “Come on, buddy,” he said. “The team needs you!”

Anthun had originally tried out for the basketball team, and he was disappointed when he didn’t make the final cut. But Borman and Miller told him that being a manager was a way to still contribute to the team. By the end of the game, he’d handed out every bottle of water and had even begun keeping individual stats for the players. After it was over, he helped clean up the gym—throwing away trash and putting chairs back in the closet. “Playing didn’t work out for me this year,” he said, “but I learned that I really love coaching. If I keep it up as a manager, I’ll show them I’m worthy of being a coach. That’s what I want to do now.”

He paused.

“Well, either that or work in real estate. Maybe I could sell houses to NBA players.”

Photos via Mike Lawrence.