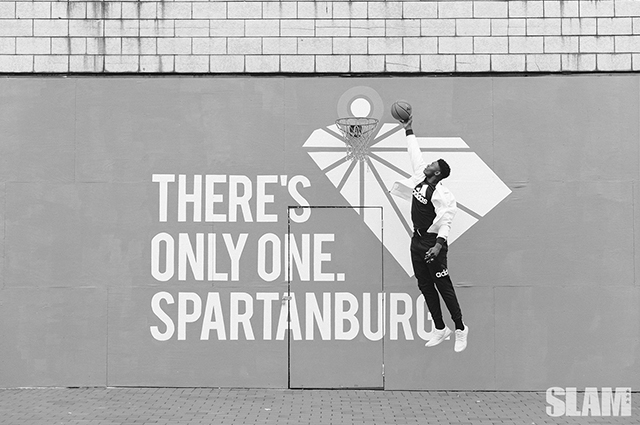

There’s a mural on a wall in the downtown area of Spartanburg, SC. On top of a royal blue background, the words “THERE’S ONLY ONE. SPARTANBURG.” are painted in white alongside an outline of the state of South Carolina, with various lines cutting through and connecting at the point in the state’s northern region where Spartanburg lies.

It’s a classic small-city welcome, some nice public art that locals and visitors can take pictures in front of to post on Facebook or Instagram or wherever. But today, on this rainy mid-May afternoon, the mural looks a little different than it has in the past. That’s because a basketball hoop has been hammered into the wall right where those in-state lines meet. Spartanburg resident Lee Anderson put it there thinking it’d spruce up the photos. He was right.

Not only does the hoop help create some fun pics, it also perfectly encapsulates the pulse and heartbeat of Spartanburg at this moment. Sure, the closest NBA team plays about two hours away in a totally different state, and South Carolina is traditionally considered football country, but on this day—and in this week, month, even year—Spartanburg revolves around basketball. All because of one individual. A 16-year-old student who attends nearby Spartanburg Day School.

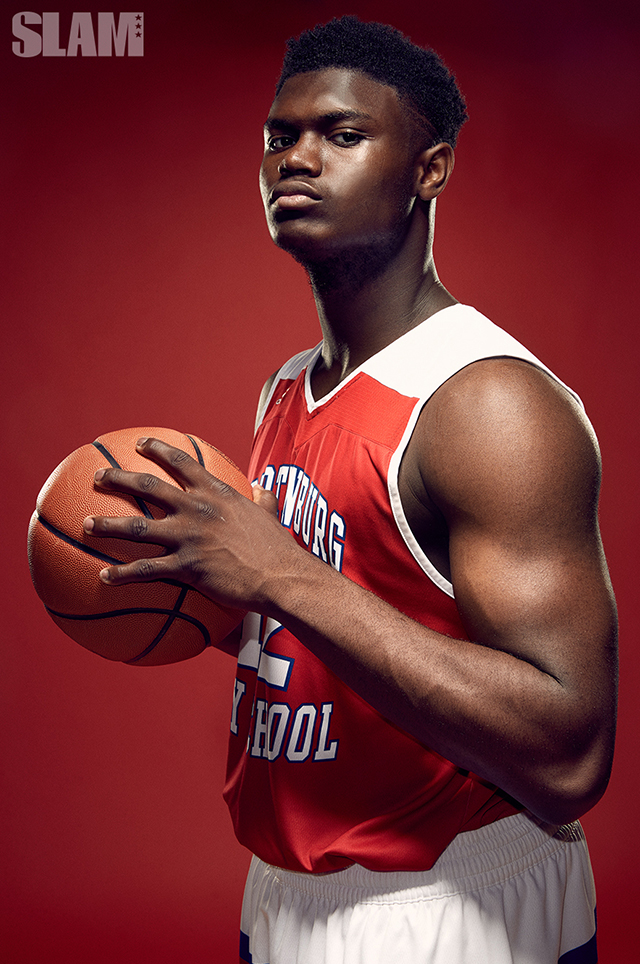

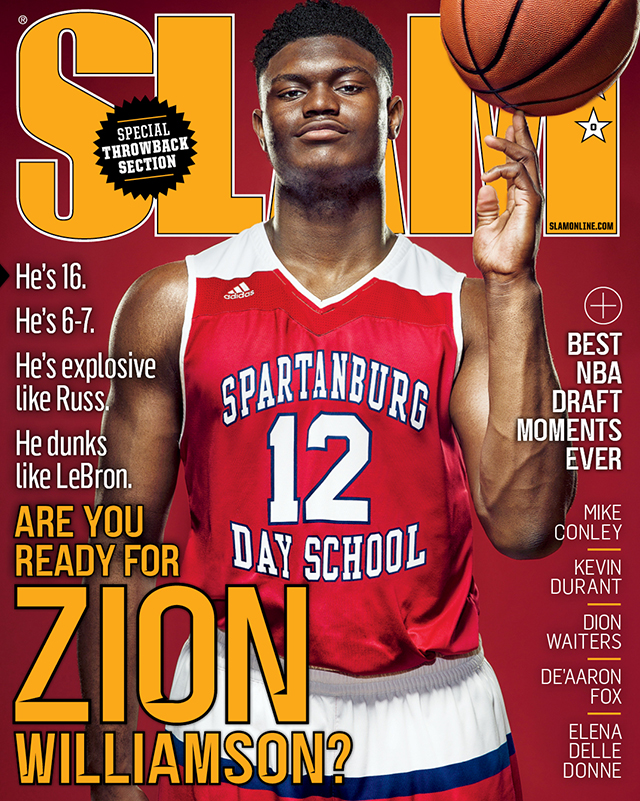

His name is Zion Williamson.

You’ve probably heard of Zion. If you haven’t, you’ve almost definitely seen videos of him on one of your social media feeds, likely soaring through the air for some mind-boggling dunk that doesn’t look like it should be possible at the highest professional level, let alone from a teenager who isn’t legally allowed to vote. A little over a year ago, Zion first made headlines when he caught an alley-oop and finished a dunk over a helpless defender, whom Zion then stared down as the entire gym exploded in celebration. When it happened, Williamson was 15 years old and the No. 17-ranked player in the Class of 2018, per ESPN’s rankings.

He balled out through the summer of 2016, taking home co-MVP at the NBPA Top 100 camp, winning co-MVP and the dunk contest at the Under Armour Elite 24 and just generally dominating the AAU circuit. Then his junior season hit, and so did the dunks, the huge stat lines, the viral highlights, the mixtapes—all of it. One after the next after the next, each game containing anywhere from 30 seconds to a few minutes of must-see internet fodder. On at least a couple of occasions each game, Zion would grab a rebound or catch an outlet pass, dribble into the open court or through the defense, and rise up and dunk with a ferocity never before seen from a high schooler. Ever.

“You think he’s going to make a regular play,” says Lee Sartor, Zion’s high school coach at Spartanburg Day, “and it starts that way, but he finishes with such power and force that it just shocks your soul. You’re just amazed by what you just witnessed. And you want to see it over and over again because it’s just so unbelievable.”

Zion stands about 6-7 (and he could still be growing) and weighs around 240 pounds. He’s a lefty with the handles of a point guard and the dunking ability of…well, nobody that’s come along yet. Maybe Vince Carter? Dr. J? Dominique Wilkins? A slightly less springy, definitively more powerful version of Zach LaVine? It’s tough to put into context something that is arriving for the first time.

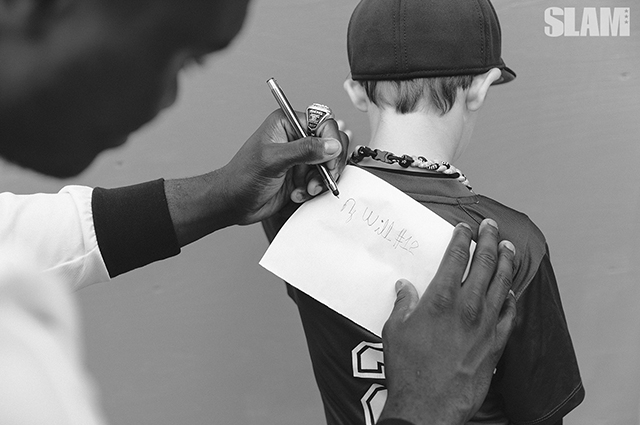

Those highlights, mixed with the level of command Zion was demonstrating on the court through his junior season, have turned him into a celebrity of sorts. All of the team’s home and away games are packed. Fans have traveled hours on end to watch him play. After one road game, the post-game atmosphere was so crazy that the players and coaching staff had to band together and bolt through a tunnel out of the back of the gym and run to the team bus. “I remember as we were running, I could imagine how The Beatles felt, with people running after them,” Sartor says, only half-joking. And Zion, who as a youngster asked for autographs from the highly-touted high school basketball players he admired, makes a point to sign every autograph and snap every selfie asked of him.

“I think people are realizing that they’re witnessing the beginning of something that could result in them saying, ‘I saw this kid when he was just starting, and now he’s perhaps the best player in America, or the planet,’” Sartor says. “I think people want to get a glimpse of that. It’s a show, and Zion realizes that his game and the way he plays, it excites people and inspires people and entertains people. He could, sometimes, just shoot a jumpshot or make a finger roll, but he knows that people are amazed by what he can do above the rim and finish with dunks, so that’s what he does. He wants to entertain people. People get excited by the way he plays.”

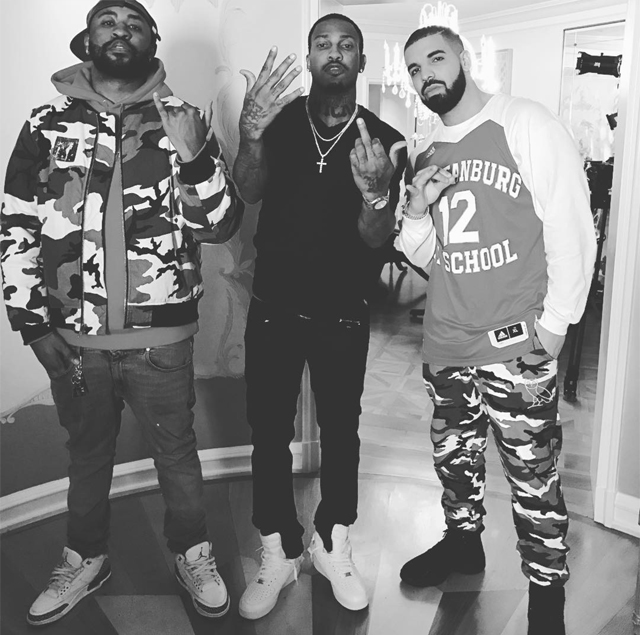

Williamson’s buzz hit another level last January when Drake posted a photo on Instagram of him wearing Williamson’s No. 12 Spartanburg Day School jersey. Zion was sound asleep as the image spread.

“I woke up probably around 8-ish,” he says. “I had hundreds of messages—group chats, like 50 Snapchat notifications. My phone just blew up. They were all like, go check Instagram, look what Drake just posted. I saw that he had my jersey on, and I sent him an IG message that said, ‘Thanks for showing me so much love—I don’t think you understand how much this means to me. You’re my favorite rapper.’”

The two haven’t met in person yet but text here and there. And to answer a question Zion often gets—no, he didn’t send Drake the jersey. “I asked him myself,” Zion says. “I said, ‘Yo, how did you get that jersey?’ He said he had it custom made. I just left it at that.”

From there, the celeb love branched out. Odell Beckham Jr also wore the uni and posted a pic on IG. Floyd Mayweather FaceTimed with him. Dez Bryant, Nate Robinson and Dwight Howard all sent messages.

When we catch up with Zion, he’s sitting in the Spartanburg Day School gym, seated upright on a folding chair under a basket during his first SLAM cover shoot. It’s in this gym where many of the viral videos originated—the bleachers and area surrounding the court filled with people standing up and high-fiving, hugging one another and yelling their faces off after any of Zion’s miraculous dunks.

“It’s an adrenaline rush,” Zion says. “It just gives you so much energy. When I get the ball or a steal and I’m wide open, you just hear everybody rise, and you hear, ‘Ohhh…’ and then you dunk it, and everybody’s jumping, high-fiving each other, and you’re just running down the floor like, Let’s go!

“I love it,” he adds. “When I was a little kid, even though I didn’t know what advanced dunks were—like windmills, 360s—I used to just want to see somebody dunk. Like, ‘Can you dunk? Dunk it!’ So when I see little kids go, ‘Zion, dunk it!’ I just look at them and say, I got you.”

Shortly before our interview, Zion, back on the court after a few weeks away from the game while he rested a bruised knee, does some “light” dunking for the SLAM photographer and videographers who are documenting the day. As he gets loose, I stand at halfcourt, watching. Eventually he takes a real running start, then leaps so high and throws it down with such fury that I contort my body in a full twist as I try to absorb what on earth I just witnessed. The aforementioned Lee Anderson—Zion’s stepdad—looks over at me and asks, “Are you OK there, Adam?” I tell him yes, but the answer is no. I’ve been to five NBA Slam Dunk Contests. I’ve never seen anyone dunk like that.

Part of the interest in Zion’s story comes from the fact that all of this—these dunks, this photo shoot, those highlight-reel games (at least the home ones)—is taking place in South Carolina’s Spartanburg Day School, a random private school with a sprawling campus in a relatively nondescript small city in South Carolina. To say that this school isn’t exactly a traditional basketball powerhouse would be quite the understatement. The entire school has an enrollment of 450 students, and that accounts for 3K (preschoolers) all the way up through 12th grade; the “Upper School,” which consists of grades 9-12, has about 150. The school doesn’t have a full-time basketball coach, and Sartor, who moonlights as the school’s varsity basketball coach, has a full-time gig as a Sheriff’s Deputy for Spartanburg County, though he says these days coaching basketball keeps him busy enough that it’s close to a full-time job.

“The school is small, intimate,” says Sharonda Sampson, Zion’s mother. “It’s not like when you go to a large high school and you get smothered. That doesn’t happen here. He goes to school with kids of people who own major corporations. So it’s like, ‘Basketball? OK, whatever.’ They see Zion, and he gets some attention, but they don’t bother him. They just like hanging out with him and being his friend.”

And like the school, Spartanburg as a city has not experienced anything like Zion. Football players, like former NFL running back Stephen Davis, have come out of the area, but never any big-name hoopers. (And Davis went off to Auburn as the No. 1 recruit in the country 25 years ago.)

“Usually you’re talking about what a community is doing to help nurture and do what’s right for teenage kids,” says Will Rothschild, Vice President of Strategic Communications of the Spartanburg Area Chamber of Commerce. “In this case, it’s a teenager doing a whole lot for his community. It’s a little odd to talk about—but it’s great.”

Rothschild gives an example of just how much attention Zion has brought upon the area: Last summer, Spartanburg hosted an AAU tournament that Zion played in, and the college coaches’ private jets were coming in at such a rapid pace that the local airport almost ran out of free space.

Zion isn’t originally from Spartanburg, though. He was born in Salisbury, NC, and moved to Florence, SC, when he was a toddler. Zion’s parents divorced when he was 5; his mother would later marry Anderson, who played guard at Clemson and then Columbus State in the late 70s. Anderson coached an AAU team and ran a basketball camp that Zion played in during the summertime.

“Zion came in very young, and he would get the basic stuff,” Anderson says. “From 9-5, every day [during the summer], for about six, seven years. That pushed him way over the top. Basic fundamentals, ballhandling, shooting, defense, rebounding drills. He got it all at a young age. That’s how he got ahead of his class.”

“I sucked,” Zion says. “But playing the game of basketball, it’s like a love—my first love. When you start playing, you don’t wanna stop.”

Zion wasn’t very tall, so he learned how to play point guard. “He mastered that pretty good,” Anderson says. “When he got to sixth grade, I just knew he would be way beyond the middle school competition. When he got to seventh grade, he was just dominating.”

Anderson had known Sartor from the South Carolina AAU circuit, and the family moved to Spartanburg at the beginning of Zion’s ninth grade year. The thought was Spartanburg Day offered a better basketball opportunity than where they were in the Florence area, and if hoops didn’t pan out, Zion would be getting a strong education in the process.

Uhh, good news—hoops panned out. As an eighth grade PG, Zion stood around 5-10, but he grew to 6-3 as a freshman and to 6-6 as a sophomore. He finished all-state as a freshman, but his team lost in the state championship and he went into that summer without any scholarship options. The following season Spartanburg Day won the state championship, and Zion hit summer ’16 with offers to local colleges like Wofford and Clemson. Then he played at a tournament in Dallas, where he picked up an offer from Iowa State. “So I’m like, OK, I can definitely go to college to play basketball,” he says. Next up was a tourney in Atlanta, where he left with “like 20” scholarship offers. He had arrived.

Zion is now a legitimate 6-7 forward but maintains the floor general skills he honed as a middle schooler with an added bounce unseen elsewhere on the high school scene. “This athleticism people keep telling me I have, it just came outta nowhere,” he says, smiling.

His game is undeniably similar to a certain previously buzzed-about high school recruit. He’s maybe an inch or two shorter than LeBron James was at the same age, and Bron was a better passer, but Zion is a better dunker and either equally or even more athletic at his size. They both were and are more than capable ballhandlers, both had and have seemingly NBA-ready bodies as high schoolers. Like Bron, Zion will need to improve his outside shooting, but if King James has taught us anything, it’s that perimeter skills can be improved immensely with hard work and time.

Zion’s stats have backed up the highlights. Per MaxPreps, he averaged 36.8 points and 13.0 rebounds this season, leading Spartanburg Day to a second consecutive state championship, albeit against lesser competition than some of his peers at basketball powerhouses—though in December he dropped 53 points in a victory over five-star recruit and future UNC guard Jalek Felton’s Gray Collegiate Academy, shooting 24-24 inside the three-point line and 25-28 overall.

He says he’s comfortable at Spartanburg Day, yet naturally many wonder if he’ll play out his senior year there or take off for tougher comp at one of the HS hoops factories across the country. And then, of course, there’s his college decision. He says his recruitment is wide open, with Kentucky, North Carolina, Duke and South Carolina considered to be at the top of the list. The college coaches have been so relentless in their recruiting that the family had to instill a rule: No phone calls or texts after 10 p.m. EST. “It’d be like 11, 12 o’clock, and coaches are calling, and we’re like, Wait a minute, do they not know you have to go to school tomorrow? You still need your rest,” Sampson says. “We were just like, OK, at this time, the phone goes on airplane mode.”

It’s no secret what Spartanburg’s residents are hoping for. As Zion takes photos in front of the “THERE’S ONLY ONE” mural, a man driving past in a pick-up truck yells, “Go to South Carolina!”

“Maybe!” Zion chirps back.

Time will tell where he ends up for what will likely be his only season of NCAA ball, just as time will tell how Zion’s game evolves from here. As an athletic wing who can handle the rock or do work in the paint on either end, Williamson’s well-rounded skill set makes him perfect for the increasingly position-less direction the game is heading. Like any teenager, he’s got a ways to go—some are skeptical that he’s even the best player in the Class of 2018, a title he competes for with Marvin Bagley III, a 6-11 power forward from Arizona. But there’s no debating that the future is bright. As a young child, he obsessed over tapes of Magic Johnson, mimicking Magic’s iconic no-look passes, and he now studies his three favorite players: LeBron (for his on- and off-court reputations), Kawhi Leonard (for the drama-free way he handles his business) and Russell Westbrook (for his ever-intense drive).

“I want to be one of the greatest that’s ever played this game,” Zion says, before listing off his personal goals. “I want to have a great reputation—nothing bad. Be a Hall of Famer. Try to win at least three NBA Finals, even though that’s probably nearly impossible, or very hard—but I’ma try. And give back to my community.”

There’s a lot of work to be done before any of that happens, but Zion is on the right track. His upbringing has provided him with such a strong backbone that texts from Drake and direct messages from a plethora of major celebrities haven’t gotten to his head. His status as a perpetual highlight reel in an era when bite-sized highlights thrive like never before means the spotlight will always shine bright. And his game suits the current landscape of pro basketball—and will likely suit it even better five-plus years from now.

Even his name is prescient. Mount Zion was the highest point in ancient Jerusalem. This Zion has begun his ascent to a height most of us can barely fathom. All we can do now is look up.

—

Adam Figman is the Editor-in-Chief of SLAM. Follow him on Twitter @afigman.

Portraits by Zach Wolfe

Action photo via Alex Hicks Jr/Spartanburg Herald-Journal and Goupstate.com

Videos by @VASHR