It’s 7:30 p.m. on his night off and Tony Allen—aka The Grindfather—is out proving how he got his nickname.

Allen is putting in work at the New Orleans Pelicans practice facility, where the parking lot is practically empty, it’s pitch black outside, and the inside is library quiet.

The previous night, the Pels beat the reigning Eastern Conference champion Cleveland Cavaliers to reach .500 for the first time since the 2014-15 season. After the final buzzer, Allen rushed out to the facility to get shots up, ’cause, as he likes to say, “Proper preparation prevents poor performance.”

Less than 24 hours later, he’s back. Grit ’N Grind doesn’t take a night off.

“I want to show you the grind,” Allen says while he puts on his shirt inside a barren Pelicans locker room. “A lot of motherfuckers talk about the grind, but I want to show you.”

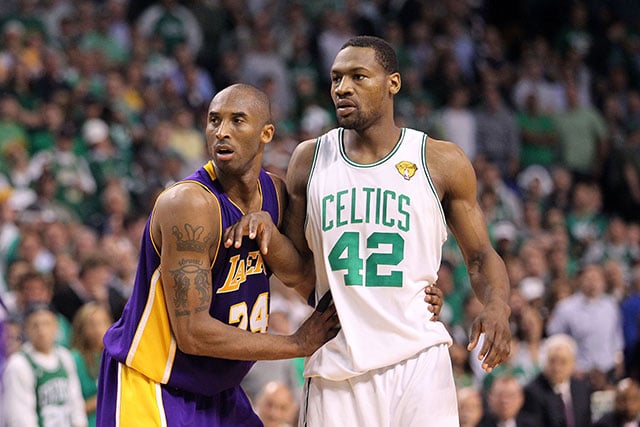

Allen has never averaged more than 11.5 points in a season, never grabbed more than 5.5 rebounds per game. But he’s spent the last 14 years bullying opposing ballplayers to the point where Kobe Bryant said he’s the best defender he ever faced. He’s the personification of grit, not glitz.

And while he’s best known for screaming “First Team All-Defense” during a 2015 playoff matchup with the Golden State Warriors, the one phrase he keeps repeating is drenched in humility: “Coming from where I come from.”

“I never ever want to go back,” he says of his childhood neighborhood. “Seeing some of my homeboys in wheelchairs now and seeing some of my guys who can’t even walk the same—they were in areas where shootings can happen at any time.”

Allen was born in Chicago in 1982 and spent most of his upbringing on 95th Street and Princeton Avenue in the Southside part of the city. Allen describes it as a “real rough neighborhood” and fell into a life of crime at a young age.

“You name it, I did everything under the sun,” he says. “I never was a thief, [I was] more trying to hustle. Not scam—hustle. Move drugs. That’s the reality of my situation.”

Once in high school, Allen quickly gave up on academics. He didn’t have the grades to play sports during his freshman and sophomore years, so he’d roam the halls, hitting all the lunch periods, looking for someone with money that he could play dice with. That summer, he decided he was going to drop out of school, help his cousin hustle on the streets and start his “adult life.”

Allen spent so much time away from home, he came back one day to find his mother Ella had moved, refusing to live with him and enable his behavior. He had to find out through family that she had taken off for the Chicago’s West Side and would not tell her son the address until he proved he was in school and staying out of trouble.

That led to what Allen calls his “cold summer.”

The days became a never-ending cycle of hustling, running from the police, getting guns pulled on him, getting in fights, getting shot at and police raids. A gruesome scar that was the result of getting pushed through a window during a fight covers most of his left forearm, a constant reminder of that low part of his life.

Then came rock bottom. Allen and his crew were out selling drugs in a neighborhood they weren’t supposed to be in. They were shot at. One of his friends returned fire and hit the initial shooter.

After fleeing the scene, Allen thought he was home safe. Then retaliation arrived.

“I was sitting on the porch,” he says. “I thought it was over with. All of a sudden I saw 50 guys walk in front of me, like, ‘Who’s the chief in command over here?’ I’m like, Hold on, I’ll go get him. Just don’t do anything to me. That’s when I knew that wasn’t going to be [the end of] my life, ’cause they could’ve easily retaliated. I was like, That was too close.”

Literally the next day, Allen’s life completely changed. He decided to go to a local Pro-Am where he heard NBA players and Chicago natives like Quentin Richardson, Antoine Walker and Michael Finley would be playing. He brought his gear just in case someone needed an extra body. Luckily, a buddy of his asked if he wanted to play, to which Allen responded, “Hell yeah.”

Future NBA player Will Bynum was also in the house and familiar with Allen from when they played together as third graders. He told Allen to attend Crane High School and play with him.

With Allen’s past, he had to attend school from 7:30-4:30 every day to get a diploma, but grinding was never his issue. After enrolling in school, he called his mother to finally convince her that he was turning over a new leaf and should be allowed to move back. Ella told him her address, and as if it was fate, she was living just four blocks from Crane.

Since Allen never played AAU ball, he wasn’t a known commodity to college recruiters. A friend told him to try out at Butler Community College in El Dorado, KS, and Allen took his first-ever flight down to play in a scrimmage at the school. Afterward, the coach asked T.A. to sign a letter of intent. He immediately called his mother to let her know her son was a college boy.

“Momma, I love getting on planes, and guess what else? I’m fitting to go to college,” Allen told her over the phone. Her response: “Get the hell out of here.”

“She didn’t believe me!” he says now.

After getting in trouble at Butler—he politely declined to elaborate on what happened—Allen transferred to Wabash Valley College in Illinois, the then-reigning junior college national champions, for the 2001-02 season.

From there, he started getting looks from a handful of DI colleges, but Oklahoma State showed the most interest. Allen decided to attend OK State for his junior and senior seasons and, during his final year on campus, was named Big 12 Player of the Year en route to a 2004 Final Four appearance. There, Allen and the Cowboys fell to Georgia Tech on a last-second layup from none other than Will Bynum.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Allen says. “It was just a dream come true for us to both be in the Final Four together. Nobody could write that story.“

Allen entered the ’04 NBA Draft and was selected 25th overall by the Celtics. Once in Boston, he was given advice from his head coach and fellow Chi native, Doc Rivers, that changed the path of his career.

“Doc Rivers was always telling me, ‘Defense is going to be your niche, son. You’re going to stay in this league 10-15 years off defense. Trust me. This is your niche, son.’ I believed him,” Allen says.

In Boston, Allen teamed up with Paul Pierce, a player whom he admired from afar and had played as during games of NBA Live 99 on Sony PlayStation.

Allen impressed enough during the beginning of his rookie year that reporters began to ask him about making the 2005 Rising Stars Challenge at All-Star Weekend in Denver. “I remember telling reporters, I really don’t know. I’m really focused on winning ballgames,” Allen says. “I said, I’m not worried about it, and [Pierce] said, ‘Man, quit lying. You know you’d love to play in the [Rising Stars Challenge]. Matter of fact, you make the game, you can have this watch.’ It was a $30,000 Jacob [and Co.].”

Allen ended up making the game. And Pierce ended up gifting him that watch.

T.A. was a member of Boston’s 2008 championship team and stayed with the franchise until 2010, when he inked a deal with a promising Memphis Grizzlies team.

“Memphis was fitting to be something special,” Allen says. “I saw that way before I got there. But when I got there, they didn’t see that in me. Not at first. I had to make them believers as time went on.”

Allen initially struggled to get consistent PT because Memphis was trying to develop its 2010 lottery pick, guard Xavier Henry. Then, during a February 2011 matchup with the Thunder, T.A. scored 27 points and guarded Kevin Durant in an OT win. Following the performance, Allen took a subliminal shot at a teammate who decided he didn’t want to play that night.

That subliminal turned into a way of life for the Grizzlies franchise.

“All heart, grit and grind.”

A few weeks later, Henry suffered a knee injury that caused him to sit for an extended amount of time, giving Allen the opportunity he’d been waiting for.

“He always told young players, ‘Stay ready so you don’t have to get ready,’” says Chris Vernon, a Memphis radio personality and friend of Allen. “He got his chance, was shot out a cannon, and the rest is history.”

A few years later in the 2015 playoffs, the nation got a real taste of Allen’s blue collar bravado, which had already become legendary in Memphis. Against the No. 1-seeded Warriors, Allen was mic’d up by TNT. After stealing the ball away from Klay Thompson, Allen looked at his teammates, put a single finger in the air and yelled what has become his catchphrase: “First-Team All Defense.” The All-Defensive teams hadn’t even been announced yet. Allen didn’t care.

“I don’t know what possessed me to do that,” Allen says. “I guess it was the fact that I thought I got snubbed the year before. [2014 was the only year he hadn’t made the First or Second All-Defensive team since 2011.—Ed.] I knew I was one of the top five defenders in the world. That’s a fact. So I was just saying facts.”

This past offseason, Allen left Memphis to sign with New Orleans, where he’s imparting his wisdom on a promising Pelicans team. But his heart, legacy and No. 9 jersey will always be with Memphis. During the preseason, the Grizz announced his number will eventually be retired—news that brought Allen to tears. T.A. got a standing ovation when he returned to The Grindhouse in October.

The 35-year-old Allen thinks he might play two more years in the NBA. After he retires, in an ideal world, he’d work his way up to one day becoming head coach of the Grizzlies.

“I love the city as much as the city loves me,” Allen says about Memphis. “I just gave them the real me, and they embraced the real me.”

—

Yourgo Artsitas is a writer living in New Orleans.

Photos via Getty Images