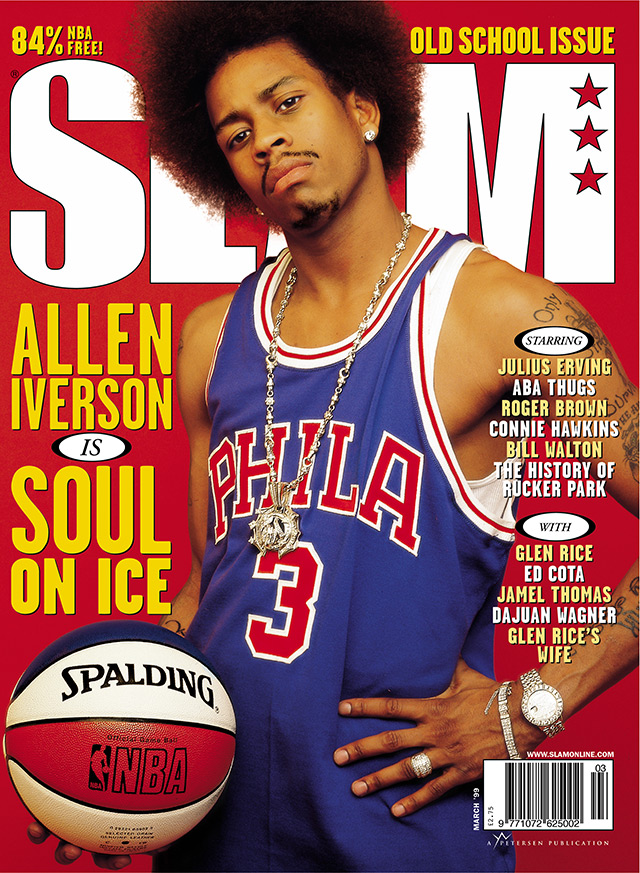

Here’s what I remember most about writing the Allen Iverson cover story for SLAM 32: The whole interview took place in the back of a limo over the course of a NYC morning, and we made one stop at Jacob the Jeweler on 47th Street so he could get his diamond and platinum cuff fixed. Given the recent stories this plays tragic, but back then it’s just how things were. And besides, this was when Iverson’s prime earning days were still ahead of him—as were the All-Star appearances and scoring titles (he’d win his first that lockout-shortened ’99 season) and his lone Finals appearance and MVP. There was no thought of legacy, of how any of this would seem a decade and a half down the road. In fact, aside from the bling, Iverson was a purer practitioner of Zen than Phil Jackson, forever living in the moment, playing each game like it could be his last. He was also one hell of an interview, even on a sleepy morning. Enjoy.—Russ Bengtson

Originally published in SLAM 32 (March, ’99)

by Russ Bengtson / portraits by Clay Patrick McBride

Shut up.

All of you who have been talking, writing, miming about Allen Iverson’s posse, his hair, his Benz, his jewelry, his clothes, his music. Stop for a minute—just a minute—and listen. (The previous sentence should have read “Stop for a minute—just a minute—and watch,” but since the NBA seems intent on killing itself, listening will have to do.) Listen to the one person who has any real stake in Allen Iverson’s life.

Listen: Anything that has anything negative to do with my name, negative people will bring it back up, and they’ll try to tear me down. But it’s going to be like that for the rest of my life, you know?

Allen Iverson says this from the back of a black stretch Lincoln, slowly rolling through New York City traffic, Primo-blessed All City flowing through the speakers. Draped in his signature Reebok fatigues and enough ice-dipped platinum to ensure Patrick Ewing’s family’s “survival” for countless generations, Allen Iverson sounds like a hypocrite. Just another young superstar with an attitude. Look at the 23-year-old with the jewels and the shady friends and the arms full of new tattoos, worrying about getting torn down. Isn’t he doing that himself?

Listen: I dress the way I want to dress, I look the way I want to look— people don’t understand. “He wanna wear the cornrows, and all that, it’s supposed to be some thug image.” It’s not that. It’s I’m tired of being on the road—I go out and I have a game and I wanna get my hair cut, the barber pushes my hairline all the way to the back of my head. I’m tired of that, so I get my hair braided and I can wear my hair like this for two weeks and play two, three games. I’ll never cut my hair again. My son, I’ll never cut his hair. He’s gonna wear cornrows—is he a thug? You know it’s not about that. I guess I am hip-hop, but I’d rather be like that right now. When I get to 30 or maybe—well, I’m 23, and maybe when I get to 24 I’ll want to change.

Explanations can be awfully simple when you let them come out. Allen Iverson isn’t trying to be a gangster—he just never had the chance to be a kid. He grew up poor, spent his 18th birthday in prison on trumped-up charges that were later dismissed. After that, two years under John Thompson’s lock-and-key at Georgetown, then, at the ripe old age of 21, introduced to Philadelphia as the Savior. Black Jesus, Part II. When your name’s been in the headlines since high school, your life is no longer your own.

Listen: You know, people just make mistakes; everybody makes mistakes. The people that write them negative articles, they make mistakes—if not every day, every other day. The same person that’s bashing you on TV, whether it’s a commentator or reporter, that same person has made mistakes in his life but was never in the spotlight, so people didn’t hear about it, you know what I’m saying?

Allen Iverson spends a lot of time defending his life. Too much time. People forget what it’s like to be 23—and will never understand what it’s like to grow up the child of a 15-year-old mother in a crowded house with raw sewage on the floor, and then be given a ticket out. Not only a ticket out, but the ticket—virtually unlimited riches, millions of adoring fans. Success came quickly. Iverson scored 30 points in his first game on 15-19 from the floor; last year’s stats (22 ppg, 6.7 apg and 3.7 apg) were All-Star numbers on any other team. But for every person who wants to see him succeed, there are two hoping he’ll fail. Charles Barkley, who in his illustrious career has spit on a little girl and thrown a grown man through a plate-glass window, called him “playground Rookie of the Year.” Yet through all of this, AI’s remained the same—true to himself, true to those who’ve stayed true to him. Doesn’t this mean something?

Listen: I’m confident, not cocky.

Over the course of four hours, Allen Iverson repeats this phrase many times in many forms, as something of a mantra. It is unclear who he is trying to convince, me or him. The truth is this—whatever it is he’s got, Allen Iverson has earned the right to it. After all, who else has gone from prison to NBA Rookie of the Year? Who else, once touted as the best football prospect in the land, has emerged instead as one of the best basketball players on the planet? Who else has a crossover that broke off Michael Jordan, not once but twice?

Listen: If I played the two-guard position, I know for a fact—and I put that on everything I love—I would lead the League in scoring every single year. But the picture’s bigger than that. I’m a point guard and I want to be the point guard. I want to learn the point guard position, and that’s more important to me than having the scoring title and all that. I want to be a point guard, and that’s that. You know, I want to score and get assists and and steals rebounds and blocks—I want to do every single thing there is to do on the basketball court.

Confidence—or cockiness? Know where this is coming from: ever since AI was a shorty, his dream was to play in the NFL or the NBA. Everyone told him it was a one-in-a-million, a one-in-a-billion chance. “I always told them, ‘Not me, man. I’m different,’” Iverson says. “I always used to feel like that. I’m not sayin’ it to be big-headed or anything, but I had that much confidence in myself.” He still does. He’s earned it.

Listen: I want to be a Sixer for the rest of my career. I don’t want to play for no other team. I don’t think that’s fair to kids and fans, man, to see a guy be here and then jumpin’ around to different teams. I just don’t.

The cover is no joke. Even though he did roll in seven-plus hours late to the photo shoot, AI’s got a lotta love for Philly—a lotta love for the game. The Sixers went 31-51 last season, and A.I. wants to stay? What kind of modern-day power move is that? We won’t go so far to call him a throwback—Nate Archibald 2000, The Funk Doctor—but he’s got roots. Followed Jordan as a kid. Magic. Bird. Because underneath all the perceptions, all the lies, damn lies and headlines, Allen Iverson is a basketball player. This interview probably won’t change your view of AI—as a matter of fact, it will probably just reinforce whatever way you’re leaning. But still, do yourself a favor. Do Allen one. Listen.

SLAM: What’s your definition of a true point guard?

Allen Iverson: Someone that just understands the game, knows how to get people involved with the game. Knows when to go and when not to go. The leader on the court, the vocal leader, the leader by example. The guy who plays every game like it’s his last.

SLAM: Do you want to meet the definition or redefine the position?

AI: No, I want…I trust my coach to teach me how to be a true point guard, whatever that definition is, the real definition. Not out of my eyes, but John Stockton’s eyes and Magic Johnson’s eyes. You know, guys like that. I think my coach will teach me how to be a true point guard, the best I can be at that position. I might never be a John Stockton or a Magic Johnson, [but] I want to know the point guard from John Stockton’s perspective. I think I have more physical talents then John Stockton, but I think he knows it mentally better then me, so I’m leaving it up to my coach to teach me how to be a true point guard from his perspective and with my ability.

SLAM: I know Coach Brown has a rap for being kind of tough on point guards. Is he?

AI: Yeah he is, he is. I mean it was tough in the beginning with my coach, because I didn’t understand him and he didn’t understand me, but eventually just playing together and learning from him and him learning how I feel about different things, we got tighter. That’s what makes me look forward to this season even more, because me just putting my pride aside and listening to how he wanted me to play and run the team—it worked out. I became a better player by listening to what Larry Brown had to offer.

SLAM: Has part of it been you changing after being in the League for two years?

AI: I haven’t changed. I think my game has changed, because I have learned…you know, my first year at Georgetown, I was just reckless, because I was trying to make a name for myself. I was trying to show myself and everybody else that I could be successful on the college level and that I was a good basketball player, and I went through the same thing as a pro. I was young and I didn’t know the game and I still don’t know it like I want to know it. But I haven’t changed, I’m just learning. I guess I have changed but I’m learning—it’s not because I want to change my image; I want to change my style of play.

SLAM: At Georgetown you were the Big East’s defensive player of the year both years. People don’t really talk about that since you’ve been in the pros. Have you been paying more attention to offense?

AI: Well, they might not notice—I was fifth in steals, but people just talk about my offense. I’m not a great defensive player; I know I have to get better—and Coach Brown lets me know that every chance he gets. I gamble too much, ’cause I’m always trying to get a steal. In this league, if you go for a steal and you don’t get it, nine times out of 10 you get hurt for it, they exploit that. I’m always trying to make something happen on both ends of the court, and you hurt the team gambling a lot on defense, because once you miss a steal, the defense is on their heels.

SLAM: Do you think you can become a great defensive player?

AI: I think so. I think all that is mental. That’s like offense. Once you start believing you can become a great offensive player and you feel that way, then your body and your mind are going to respond. So, that’s that same thing with defense. There’s a lot of people that just concentrate on trying to be a great offensive player when you’re supposed to be concentrating on being a great defensive player, too.

SLAM: It seems the offense wasn’t that big a switch, though. You scored 30 your first game in the League.

AI: Offense just—I mean, whether it is good or bad, offense is just the most exciting part of any game—football, baseball, basketball. Defense, you know, you have to be really talented to be a great defensive player, because there are so many great offensive players. And to be a great defensive player, that’s special because you stopping a great offensive player. That’s like a linebacker—if you a great linebacker, that’s serious, man, to able to get to Barry Sanders every time you want to. That’s crazy, that’s talent.

SLAM: Can anybody stop you one-on-one?

AI: No, I don’t think so. And I really believe this in my heart. I respect Derek Harper, because I think he is the greatest defensive player I ever played against and I ever watched, but I don’t think he can stop me. I don’t think nobody in the League can stop me—and I know that there’s a lot of guys in the League that feel the same way I feel, so I don’t think that’s no big-headed or conceited comment. I don’t really think nobody can stop me. Maybe in college, when they ran box and ones on me, but in the NBA, where it’s just man to man? No one can stop me. A team may be able to do something with me, but no one man can stop me from doing whatever I want to do on the basketball court.

SLAM: Do you think you deserve $100 million?

AI: Do I deserve it? Yeah, I think I deserve it. I don’t know if that’s what I’ll ask for, but I think I deserve it. I think I deserve more, you know, that’s just who I am. I feel everybody deserves whatever they want, really. Whatever the franchise feels they need or want to give you, they should give it to you, you know? And that’s real. They got enough money to give people whatever, you know what I’m saying?

I think the crazy thing about this lockout [is] when you look at guys like Kevin Garnett’s salary, pshhhh, Kevin Garnett—I think—should have gotten more than what he got. And they’re able to pay him that, you know. All that money the [owners] got and they’re getting off of us, it shouldn’t be no problem—nobody’s salary. They pay Kevin Garnett what they know they can pay him. They give him this money, and everybody’s beefing, when number one he deserved it and number two they felt like he deserved it. And they felt like they had to give it to him, so what’s wrong with that? I don’t see anything wrong with that.

SLAM: Who did you start out watching when you first followed basketball?

AI: Zeke. Michael [Jordan], of course, but Zeke was always my man. I loved Isiah.

SLAM: Did you like the Pistons?

AI: Nah, I was always a Bulls fan, ever since Michael got there. I remember one time the Knicks beat ’em, and I damn near cried—I had tears in my eyes.

I was a Bulls fanatic. Because I love Mike, I love Pippen, I love Horace Grant and B.J. Armstrong and Paxson, Luc Longley, Cartwright and I just loved the Bulls, and now that I play them I hate them. Because I remember Scottie Pippen when the Knicks used to beat him all up—and you know they used to try to treat him like he was puss—and then now, for them to talk shit to me on the court while I’m playing? I still love Pip today and Mike and Dennis Rodman, ’cause they great basketball players. Then to hear the way they talk shit on the court, I’m like, “Dog, I remember when you didn’t say shit on the court, you know you was so humble and you wouldn’t say nothing on the court and now even you talk shit?”

SLAM: When did you start playing basketball?

AI: I think I was like nine or 10 years old. I always thought basketball was soft. Now I come to find out I was outta my mind, playing against Shaq and Barkley and Kevin Willis. Charles Oakley. Serious. I never wanted to play it, when my mom bought me some Jordans—I came home from school, she was like, “You going to basketball practice today,” and I was like, “I ain’t playing no basketball, it’s soft. I don’t want to play no basketball, I don’t like basketball.” I’m crying all the way out the door, she pushing me out the door. I got out there and seen kids that was on my football team and, um, I just enjoyed it. I came home and I thanked my moms, and I’ve been playing basketball ever since.

SLAM: What was your home court growing up?

AI: Newport News [VA]—Anderson Park, that’s where like it first started. And then Hampton [VA]—Aberdine Elementary School, ’cause that’s where I watched my uncles and my uncles’ friends, the people I thought that were sooo nice, so cold on the court. I watched them, and I had to play right after school—in the 8th grade or 7th grade—when it was blazing hot, like 105 or something like that. Then they came at five, six o’clock when the sun is going down, and they ran. I could never play with them, ’cause they would never let me. I guess they thought I wasn’t good enough, I was too young. And then, ninth or tenth grade, they want to pick me first—“Yo, I got AI.” It was just a great feeling, man, because that’s where I always wanted to play. [Before] they hollering at me to get off the court and they screaming at me because I was trying to play while they were playing. And then to go back and be able to play against them and kill them.

SLAM: Is there any one who you really learned the game from?

AI: Coach [John] Thompson. He the one that really taught me how to play basketball. I still don’t know it like I want to know it, but he gave me a clear picture of how to play it.

SLAM: Are you up on your NBA history? I know your rookie year was the NBA at 50, so you were at All-Star Weekend with all those guys…

AI: That was crazy, playing the rookie game and looking in the stands and seeing Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain—I was like, oh my god. Doc—Doc! It just felt crazy. I was like, I’m gonna show in front of these cats tonight. It ain’t gotta be scoring, it could be everything else, but I just want to perform for those guys. I was so hype, it was showtime and it was fun. It’s something I’ll cherish for the rest of my life. Red Auerbach—my coach—during the [rookie] game at halftime, he was like, “I don’t know what you out here doing, Allen. People came here to see you score; you ain’t have to prove no point. I understand you out here passing—and I respect that—but put the ball in the hole, too. Everybody want to see the whole game.” ’Cause I wasn’t trying to take over the whole spotlight and shine and score 30 points and all that, I was just dishing crazy, and he was like, “This half I want to see you score.” I was like, “A’ight,” and that’s what I did. In the second half, I started scoring.

SLAM: So he was actually coaching out there?

AI: Coaching. Really coaching. He was talking to me during the game, and at one point I just blacked out, I couldn’t believe he was coaching me—it felt so good man. I wanted to, right there, scream up in the stands—“Mom, did you see him talking to me? Did you see him coaching me?” I mean, he was one of the greatest coaches ever, and just for him to say something out of his mouth to me was enough. Even if it was not coaching me, even if he was just speaking to me, it would have made me feel good, but he was coaching me. I felt like crying, because I felt like I really did something in my life for me to be on the sidelines with him coaching.

SLAM: Talk to me about Doc a little bit.

AI: Doc was Mike in his time. Everybody was like—there will never be another Dr. J, da da da. That’s how crazy this thing is. Nobody ever thought there would ever be anyone better then Doc or like Doc. Or Magic, and then come Mike. It’s crazy, Doc started all that. Mike did some shit that Doc never did and vice versa, but Mike took it to a completely different level.

SLAM: What was it like playing against him for the first time? How different was it from just seeing him play?

AI: It was just wild. I can’t even remember the feeling. Just me being on his court, playing against world champions and the greatest basketball player in the world. I wasn’t out there crazy in awe or anything like that—’cause that’s just not me. I’m in the same profession you are and I respect you and what you did for your family and team, but once we get on the dance floor, I’m in a whole ’nother mode. I might feel different if I meet you before the game in the hallway, but once we get on the dance floor, I’m a do my thing and I’m not going to be in awe of nobody. But it was a crazy feeling just playing against him.

Really the only guy that flipped me out when I was on the same court with him was Sprewell. ’Cause if I could be any other basketball player, I would be Sprewell. What he did was foul, everybody know that, and I would never do no shit like that. I mean, I guess he just flipped out and snapped and he’s going to learn a lot from it and he’s a good dude, ’cause I know him as a person. But as far as talent, if I could be any other player, I wouldn’t be Michael Jordan, man. I wouldn’t take Michael Jordan’s game, I would take Latrell Sprewell’s game. I love the way he play. I love the way he play and he hard, hard on the court. You know, he might talk shit to you, he might not. He might give you 30 or 40 with a regular look on his face, like, “Whatever. This is what I do. That’s the way I play. I don’t gotta talk shit, ’cause I do this. I do this nightly. I don’t have to talk no shit to you to prove nothin’ to you.” But Spree, man. Spree’s something else.

SLAM: What is it? What is it about his game?

AI: Energy. He can play the whole damn game. He got pride with his game, you know, And he just hard. When I look at him I see myself, ’cause he don’t care who you are, he just go at you. He go right at your chest, crazy, hard. He can shoot, he can run, he can dribble, he can jump. He’s smart, he know the game.

If not Sprewell, if I had a choice, it would be Shaq. I don’t think nobody could beat my team 10 to 15 times if Shaq was on my team. Never. I mean, that guy has talent that’s just unbelievable. He’s unbelievable. If I played with him, I don’t think nobody could beat me. I don’t know if you beat me in a series, but you won’t sweep me. That’s why I look at [the Lakers] and I’m like—Utah was a great team, Karl Malone, John Stockton did great, but you got Shaq on your team. How can you live with yourself knowing you got swept and you got Shaq on your team? Shhhh…

SLAM: If Mike steps and the Bulls are no more, who’s the next squad?

AI: Who do I think? Really, in my heart? Philly. I’m not gonna say nobody else, ’cause I don’t believe that. I just believe it’s my time. I believe it’s our time. Philly was always one of the great teams. I think it’s time for that to come back.

SLAM: How bad do you want that?

AI: More than anything in the world. [Pause.] Anything. I think that’s the only thing that gonna separate me from a great player. Great players win, man. I’m not a great player. I’m nowhere near a great player now, ‘cause I don’t know the game mentally like I should. But I’m learning, believe me—I know so much more then I knew when I was a rookie, and great players win. You can be a great player, [but] if you lose, you lose. You can have the greatest stats ever, but if you lose, you lose. Ain’t nothing better than winning. When I win, then I get the respect I deserve. Until then, I’m just another basketball player. The average player, you know.

SLAM: What do you want your NBA legacy to be?

AI: Titles. I gotta have titles. Hopefully I can play, like, Robert Parish years, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar years. Hopefully. I don’t wanna go until I get some titles. And not just one. I want titles. Plural.

SLAM: Add some gold to that platinum?

AI: No doubt. Add some gold. I need it, man. I’m hungry—I’m starvin’—I’m starvin’ for success. That’s what I want now. I love lookin’ at my mom and sayin’, “You made somethin’. You made somethin’ outta me.” I love that. So I’m starvin’ for success. I mean, I wanna be good. I want to be somebody.

SLAM: How important is the individual stuff—MVP, scoring title, that sort of thing? You wanna be remembered as the best player in the game? The best point guard?

AI: I wanna be remembered as the best player in the NBA. I want to be the best, the very best. And with the company I’m keeping right now? With the guys I’m playing with? Boy. That’s a huge statement. With the talent that we got right now in this league, with the Shaqs and Grant Hills and Latrell Sprewells and Gary Paytons and Tim Hardaways and Penny Hardaways. [Pause.] That’s a big statement, but I’m willing to try and back it up. I want to be the greatest basketball player. With Michael Jordan, that’s some big words, but that’s the challenge of my life. Maybe people won’t consider me to be the best, maybe some will. Who knows? I mean, the sky’s the limit.