For some, that call of the street is impossible to ignore. Something is always happening, and if they miss it, well, that’s just too much. Got to be out. Got to be where the action is. Nothing good ever happens after midnight, you say? For Reggie Harding, very little at all happened before that magic hour.

The stories are all true. Or, none of them are. Harding shot at a teammate’s feet once to make him “dance.” His roommate awoke in the middle of the night to find Harding standing over him with a gun pointed at his head. He allegedly raped a future member of The Supremes at knifepoint.

The stories are scary. But they are just the stories. It’s really about the man, and Harding was one complicated man. He could have been a great basketball player, but he wanted to be a legend of the street. Drugs. Weapons. Crime. Parties. Reggie Harding checked off all the clichés of a hard-living existence. When he was shot dead in 1972, at the age of 30, he left behind a pile of could’ve-beens and shaking heads.

But there were moments. There always are in these stories. Harding dominated this game. He hung tough with this Hall of Famer. And he could surprise off the court, whenever he tore himself away from the trouble.

When Harding joined the Pistons as a rookie in 1963, he roomed on the road with third-year power forward Ray Scott, back when NBA players didn’t spend their idle hours in strange cities hanging out in their private suites at the Ritz. Scott was a reader, and he favored books about the struggle of blacks in America, like Richard Wright’s Native Son. In ’65, he was reading The Autobiography of Malcolm X, which was written in collaboration with Alex Haley.

“He asked me, ‘What are you reading,’” Scott says. “I told him, and he said, ‘Let me read it when you’re done.’ He did, and we sat up several nights talking about it.”

No matter how interested Harding could become in social issues, nothing had the strength to overcome trouble’s intoxicating lure. The NBA was a much different world in the 1960s, and not just because of the hotel situation. Teams didn’t have assistant coaches. When practices ended, players packed their gym bags and headed off, alone. Some went home to their families. Others lived alone. And if someone like Harding wanted to dive into the world of nefarious characters and bad-news associates, there was no one within the organization around to intervene. When he packed that gym bag, the story goes, there was often a gun in it.

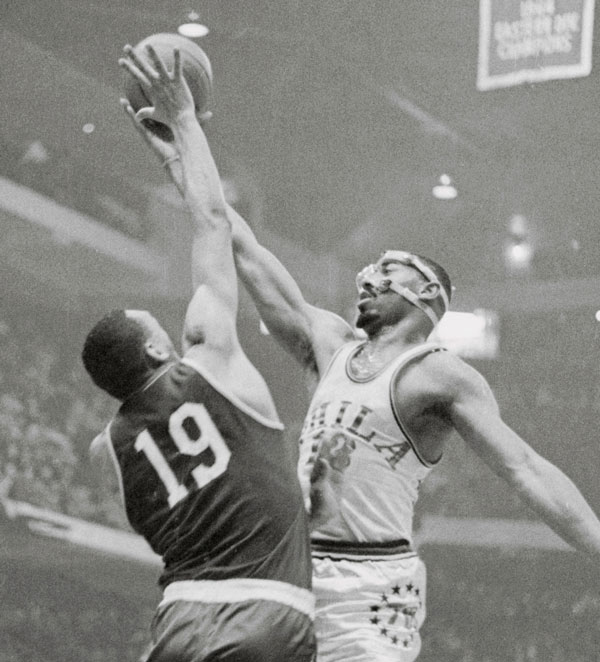

Even when his reputation had been established—he was suspended for the entire 1965-66 season—the Bulls still traded for him in 1967. It seems Chicago needed a big man (Harding was 7-feet tall) more than it needed to stay away from trouble. It wasn’t the first time a team made a compromise like that, and it has certainly happened since then. In each case, there’s a hope that “this time will be different.” It rarely is, and in the case of Harding, it certainly wasn’t.

“Reggie was a ‘could’ve been,’” Scott says. “He could’ve been so much more. He couldn’t cut his environment loose. As a tragedy, it’s almost Shakespearean. The more successful he became, the more he wanted to get back to that environment.

“He could’ve gotten out of it, but he didn’t want to.”

It’s tempting to laugh when the Harding stories are retold. How can you not chuckle when hearing about how he allegedly robbed the same gas station in his Detroit neighborhood three times. When the Masked Man hit the spot for the third time, the attendant was reported to have said, “I know it’s you, Reggie.”

“No, man, it ain’t me,” Harding supposedly said in reply. “Shut up and give me the money.”

Today, Harding’s fiasco would be included in a “World’s Dumbest Criminals” list. The problem with Harding was that he wasn’t just a bumbling crook—he was dangerous, to himself and others. The guns. The drugs. The street thugs. That’s not a good concoction. Yet, Scott won’t tear into Harding for his choices, instead lamenting the lost opportunities and blown potential.

There are others who feel the same way. They know Harding was with the wrong people at the wrong times of the day and night doing the wrong things. But the man they saw was different. He was young and careless. And the wrong people had influenced him. The wrong world.

“He was a fun guy and a nice teammate,” says Rod Thorn, the NBA’s President of Basketball Operations and an eight-year NBA vet who played with Harding in Detroit during the ’64-65 season. “He was a fun-loving guy. Like most kids, he was a little immature and didn’t take a lot of things seriously. I always got along with him. We’d kid around with each other.”

Harding was born in Detroit on May 4, 1942 and graduated from the city’s Eastern HS, which in 1968 was re-named Martin Luther King High and draws students from the downtown and midtown areas. Though Detroit has become a mere husk of its mighty former self over the past 25-30 years, it still had its problems in the late 1950s and early ’60s, as poor southern migrants continued to flood the town. For all of the grandeur spawned by the American automotive industry’s heyday, there were still plenty of parts of Detroit that struggled with crime and poverty.

Harding graduated from Eastern in 1960, eight years ahead of the race riots triggered by King’s shooting. For struggling African-Americans in the city, there was plenty of trouble to be had. College was not an option for Harding, so he played at a prep school in Nashville and for two seasons in the professional Midwest League in Toledo and Holland, MI. In 1963, the Pistons drafted Harding in the sixth round with the 48th overall pick, making him the first player ever drafted who hadn’t played in college. He played 39 games that year, averaging 11.0 ppg and 10.5 rpg. It was clear he had talent. The next season, Harding averaged 34.6 minutes in 78 games and scored 12.0 ppg while pulling down 11.6 rpg for a Pistons team that finished fourth in the Western Division.

“I thought he was a player with big potential,” says Thorn, who joined Detroit that year. “He had a great body, long arms and was very long. I thought on the defensive end of the court he had tremendous potential.”

Yes, Harding had potential. But he had nobody to get him beyond that point. Look at an NBA bench today, and you’ll see a battalion of assistant coaches and player development specialists. Someone young, raw and 7-feet tall like Harding would receive constant attention at practice and before games. The team would devise a nutritional strategy for him. It would customize offseason workouts to maximize skill growth. That wasn’t the case in 1964. Detroit’s case was even more removed from today’s model, since nine games into the season, star forward Dave DeBusschere took over as coach. That meant it was even less likely Harding would get individual attention.

Not that he really wanted it. Often, Harding went straight from practice to the club. And sometimes, he came straight from the club to practice. He was young and fun-loving, but he wanted too much fun.

“In order to develop your basketball skills, you need discipline,” Scott says. “His lack of discipline affected his stamina. It was just a matter of not taking care of himself and getting his rest.”

The NBA suspended Harding for the entire 1965-66 season. There are those who say the reason is unknown. Others report it was because of his legal problems brought on by weapons charges. That makes sense, because Harding was rarely too far from a gun. Though he returned to the Pistons in ’67, he played only 18.5 minutes a night and his averages fell to 5.5 ppg and 6.1 rpg. It was clear that the streets were in control. Whether it was booze, drugs, women, gunplay or general bad behavior, Harding was a part-time NBA player and a full-time gangster.

“When the game ended, I used to ask Reggie where he was going and say, ‘Keep your nose clean,’” Scott says. “But there were always four or five guys waiting for him from the neighborhood. It was a question of who you’re going to listen to.”

Before the 1967-68 season, Detroit dished Harding to Chicago for a third-round Draft pick. His stay with the Bulls was brief, only 14 games. The team opened the season 1-15, and then-coach Johnny Kerr often told a story about how the team held a 1-point lead over the Lakers with only a few seconds left. L.A. had the ball, and Kerr assigned Harding to guard Los Angeles center Mel Counts. When Laker guard Walt Hazzard threw the ball over the backboard, Kerr rejoiced, thinking the Bulls had won. But Harding had knocked Counts to the ground away from the play and Counts was awarded two free throws. He made both, and Chicago dropped a 97-96 decision.

Harding’s career ended with a 25-game stint in ’67-68 with Indiana of the ABA. He played well, scoring 13.4 ppg and hauling in 13.4 rpg. But Harding couldn’t get it right off the court. He threatened to kill team GM Mike Storen during a televised interview. Harding pointed a loaded pistol at roommate Jimmy Rayl, convinced Rayl was a racist. Even in the wild ABA, Harding stood out as the ultimate Dangerous Man. When the season ended, he actually owed the Pacers $400, because instead of settling for the $10,000 the team offered, Harding opted for $300 a game and was fined so much for missing practice or showing up late for flights that he was in debt.

That was it for Harding, the basketball player. The man suffered a worse fate than being released and ignored by professional teams. On September 2, 1972, Harding was shot at an intersection in Detroit. No one can pinpoint the reason for his slaying, but it’s not hard to imagine a deal gone wrong, a beef with some local tough turning sour, or just the random violence of the street.

“A lot of people were very emotional about Reggie,” Scott says. “Some people viewed his story as a fault of society. Society did fail him, but we were never able to get him off the street. In my opinion, Reggie was where he wanted to be.”

The final indignity came as his casket was lowered into the ground. The hole wasn’t big enough, so Harding had to be buried on a slant.

His life was too short. His ride was too fast. His end was too sad.

The streets aren’t undefeated, but their winning percentage is too damn high.

Michael Bradley is a Senior Writer at SLAM.