It’s been 15 years since the party and details are now murky.

Time, after all, dulls memory. Especially when those memories are mixed with a looooooong night of dark liquor, bubbling champagne and melodic violin. Still, even if the minutia is somewhat blurry, in many ways the night of June 11, 2005 was unforgettable.

For Que Gaskins, the evening actually began roughly three months prior when Tawanna Iverson reached out for help. Tawanna, Allen Iverson’s wife, wanted to throw him a 30th birthday party and she knew Gaskins, then a director at Reebok and friend of Allen’s, could help execute her vision.

The concept was simple: A surprise party, packed with all of Allen’s favorites, right at the family’s mansion in Villanova. A party that would emit love and evoke laughs. A party that would celebrate 30—an age that too many people who grew up around Allen in Newport News, VA, never reached—the way some do 80.

With a rough sketch of the event in hand, Gaskins turned around and called up Ayiko Broyard, someone Reebok worked with frequently, to help him produce the party. Broyard, led by Tawanna and with the help of her co-workers, spent the ensuing months laboring over every decoration, every morsel of food.

On the night of Saturday the 11th, four days after his actual birthday, AI crept up his circular gravel driveway. As he unfolded his pedestrian frame out of the passenger side of his luxury vehicle and brushed off his XXXL white t-shirt, Iverson looked confused. Why was Gaskins standing there?

“He was shocked,” remembers Gaskins, “[that] we were able to pull off this party without him knowing.”

Iverson was pointed toward his side yard, a swathe of grass that had been covered by a Ringling-sized white tent and a smaller sister tent. The walkway between where he stood and the tents was lined with photos. He stopped and picked one up. A toddler version of him with his mom, Ann. He took a few more steps. Him at age 9 with a football and his coach-turned-manager Gary Moore. Shuffled some more. Him in his green-and-gold Bethel High basketball uniform.

The photos traced the arc of his life—from Stuart Gardens Project to stardom at Bethel to lock up to Georgetown; from meeting Tawanna to the birth of his eldest, Deuce, to Draft night, the Finals and All-Star MVPs—in chemicals and cotton paper. Iverson, soft in the eyes and shaky in the chest, worked his way through the sticky humidity to the front flap of the tent. When he stepped inside, Iverson broke down. The scene laid out in front of him was a shrine.

The walls were decorated with action shots and portraits pulled from ad campaigns and newspapers. The ceiling was lit up in red and blue. One tent, the larger one, was populated with an open layout, a DJ booth and live music from unorthodox violinist Miri Ben-Ari. The smaller rental was highlighted by round poker tables and a TV. Both of the rooms were lined with bars with ample amounts of Iverson’s favorite champagne and food trays prepared with favorites, like crab, driven in from Newport News.

The décor was on point. The food was just what The Answer would’ve ordered. But the people present sticks with guests to this day. Three or four or maybe even five busloads of friends and family were transported up from Virginia. Ann Iverson, Gary Moore and the inner circle. Of course, Reebok reps Brian Lee, Gaskins, Todd Krinsky and photographer Gary Land. Andre Iguodala, Billy King and other former Sixer execs and teammates. Bow Wow, Charlie Mack, Jill Scott, Patti LaBelle. LeBron James and his mother, Gloria. If you were somebody, you were in that room. If you were somebody, despite it being the middle of the NBA Finals and the day of the Belmont Stakes, you wanted to be in that room.

“[Iverson] was like, ‘Why are they all here for me?’” Broyard recalls. “It was almost like a surprise, like he didn’t really know who he was or the level of influence he was having on people.”

The evening was filled with death-grip hugs. Iverson held on to Julius Erving for what felt like forever and was, soon after, tackled to the ground by James. Later, there would be an intense game of Guts and a viewing of the Mike Tyson-Kevin McBride fight.

“Despite the prevailing opinion that Mike Tyson is shot, unfocused and undisciplined,” the PPV telecast started, “this has the elements of a short and painful night for Kevin McBride.”

Six sloppy rounds later, Tyson failed to emerge from his corner. McBride was declared the winner by TKO. Iverson fell to his knees and enveloped the TV in tears. It was the end of Tyson’s career, but just the start of the party.

At around 5:00 a.m., the event staff wanted to leave. There was still more life to be soaked up. Iverson was in his element, immersed in love but unaware of the worship.

“He represented what Black kids were all about, and he resonated with every inner-city kid in the world who had a struggle,” LeBron James once told Sports Illustrated. “Michael Jordan inspired me, and I looked up to him, but he was out of this world. AI was really the god.”

Allen Iverson entered the NBA as the No. 1 pick in 1996. In his very first regular season game, Iverson was the only player to register 30 points—and the only one to sport visible tattoos. Over the next 14 seasons, scores of players would start openly showing ink, but very few would match Iverson’s career averages of 26.7 ppg, 6.2 apg and 2.2 spg.

Between ’96 and 2010, when he reluctantly retired, Iverson left dozens of defenders grasping for air—as he crossed them over or just used his speed to run by them—and even more fans gasping for air. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2016. Along the way, Iverson popularized arm sleeves, braids, headbands, tattoos and more. He didn’t invent any of it—it was authentic to the Black community he came from—but he was the first superstar to bring it with him to a national audience. In doing so, Iverson changed the NBA and, in ways, America.

“Iverson was the first [NBA player] to genuinely be himself that I noticed,” says Master Tesfatsion.

Tesfatsion, a Senior Writer and Host of Untold Stories at Bleacher Report, grew up in Section 8 housing in Dallas during Iverson’s prime and remembers window-shopping for the icon’s apparel. He also vividly remembers looking for, and rarely finding, Black people on TV that resembled him. “Athletes now say they’re ‘more than an athlete,’ but Allen Iverson helped break the mold so they could say that, so LeBron James could say, ‘I’m more than an athlete.’

“I truly believe his impact is just as relevant, if not more, than Michael [Jordan’s] to the millennial generation,” he adds.

Don’t ask Iverson about his impact. It’s not so much that Iverson’s unwilling to be an icon as it is that he is a humble one. He has a couple stock answers, and he often falls back on them in interviews.

“I took an ass-whooping for being me,” Iverson has repeated like a hook, “but if I die today, I’d rather come back as me than anybody else. I took a beating for guys to be themselves, and I love the fact that now guys don’t have to conform.”

Another bar: “A little kid saying, ‘AI, you’re my favorite’ goes a long way with a dude like me. If I ain’t nobody else’s favorite, I’m his or hers. That never gets old.”

Better to ask those around him, those influenced by him.

Gaskins spent the early part of Iverson’s career hanging with him on behalf of Reebok. A friendship blossomed. He came to understand what made Iverson transcend hoops.

“He didn’t change his taste palate because he was the No. 1 pick and on his way to becoming a global star,” says Gaskins. “He wanted to be around people that looked like him, that talked like him, that ate like him, that dressed like him.”

In that way, from night clubs with dress codes to the NBA’s social norms, explains Gaskins, Iverson was able to bend society towards his will and world view.

Many bucked, of course. They labeled Iverson a “thug.” Talked about his “posse,” hair style and clothes. Gaskins remembers that during Iverson’s rookie year, he had his own hair twisted into braids. The idea would’ve been ludicrous for a young Black man at a sneaker company a year prior, but now it felt OK. Not long after getting braids, Gaskins wore them naively to a meeting at Reebok’s HQ.

“I remember someone saying, ‘You’re supposed to be having an impact on him—it looks like he’s having the impact on you.’”

Gaskins didn’t flinch. It wasn’t a problem. It was becoming Iverson’s America.

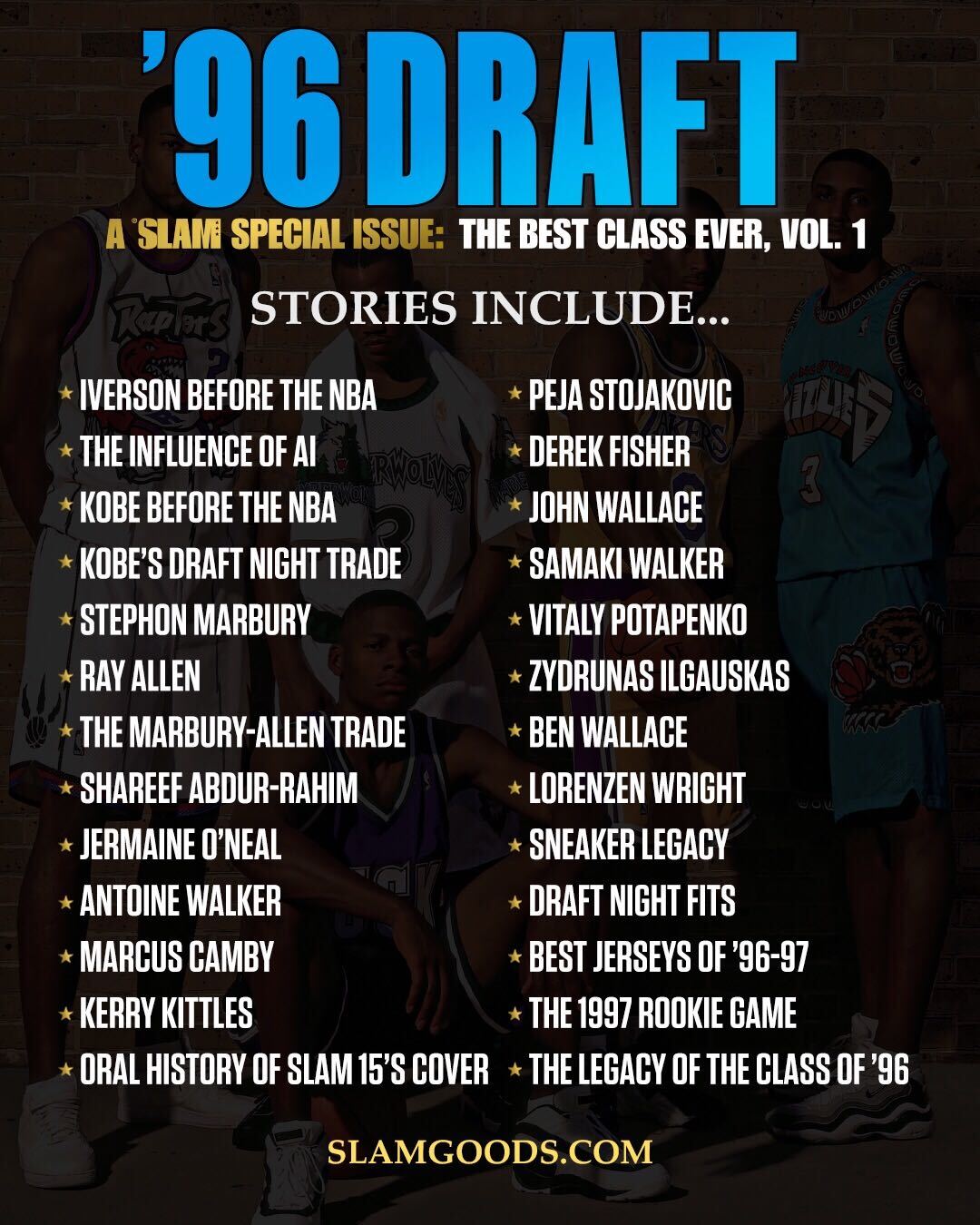

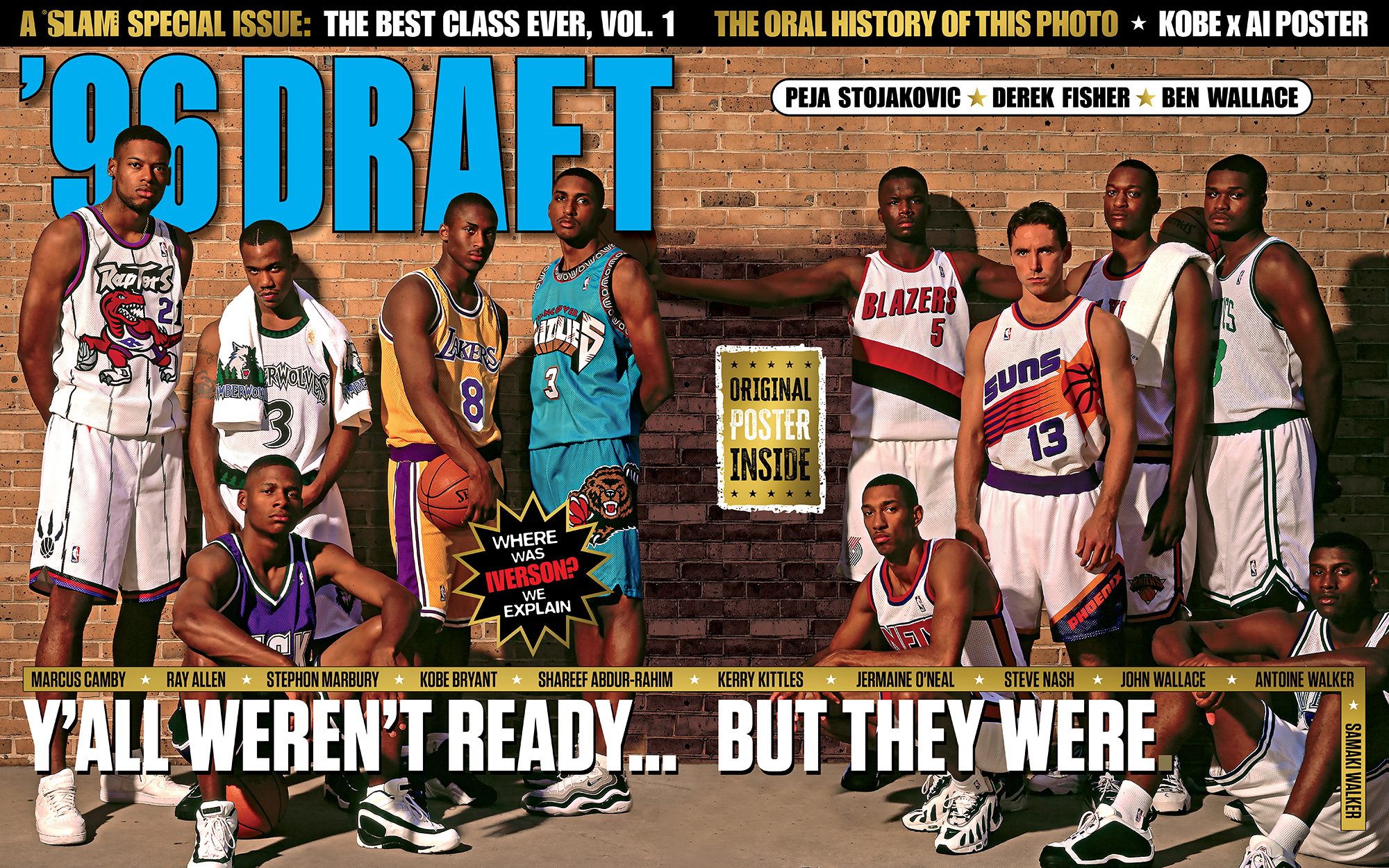

GRAB YOUR COPY OF SLAM PRESENTS ’96 DRAFT FOR EVEN MORE GOODIES FROM THE ISSUE

Datwon Thomas has a unique perspective on Iverson. He’s been the Editor-in-Chief at XXL and VIBE. He was the Founding Editor of KING Magazine and helped unearth many now-popular artists along the way. Thomas has spent an adulthood around talent, and he once spent a week with Iverson in Asia.

“Allen is a little different,” Thomas says. He remembers seeing Iverson at clubs around New York. Remembers seeing rappers sending Iverson bottles, making sure he—their favorite hooper—was taken care of. “That’s aura. You can feel it. You can tell he’s somebody, even if you don’t know who he is. Automatic.”

Madison Blank grew up in the suburbs outside of Philadelphia. As a kid, she went to as many of Iverson’s games as her father would take her to, and she had all of his signature shoes. One summer, she rocked a pair of early model Answers during the days. At night, she would take them off and tuck them into bed, dirt and all, right next to her. Nowadays, Blank helps move fashion trends. She still considers Iverson her inspiration.

“Swag and confidence are everything, and that’s him,” says Blank, Manager of Brand Relations at GOAT. She wears a gold No. 3 necklace as a form of homage. “He could be in a white tee and grey sweatpants and he carried himself like he was in a Christian Dior suit. It’s just a bravado that he has.”

Across the country, in Tacoma, WA, Isaiah Thomas also had the sneakers, had the magazine covers hung up, had the mimicked wardrobe. The undersized guard with pro aspirations loved Kobe Bryant, but he saw himself in Iverson. Saw the way he would have to play. Saw the way he could act like himself, dress like himself and still be successful.

“I’ve looked up to him, on and off the court, since I first knew who he was,” says Thomas. “He’s one of the most authentic athletes ever. Ever. Ever.

“Ever.”

Eleven years later, another party. This time Stance is hosting their annual Spades tournament to start off All-Star Weekend. Like Iverson’s 30th birthday, a VIP crowd pulls up. Dwyane Wade, the tournament’s co-host, is there with his wife and star in her own right, Gabrielle Union. Aaron Gordon, Carmelo Anthony, Chris Paul, Isaiah Thomas, James Harden, Klay Thompson, Victor Oladipo, and other influencers and hoopers fill the rest of the room.

The One Eighty, a restaurant situated on the 51st floor of a downtown tower in Toronto, was not built to host this event. It is packed to an uncomfortable degree. A few hours into the tournament, it becomes impossible to even nudge your way around the room. It’s a rush-hour subway car.

Gary Moore texts, though, that Iverson and his SUV are on the way. They show up—Iverson is in a white-and-gold t-shirt, black-and-gold fitted, gold watch and chains—and magically slip in. It is unclear who notices them, but within seconds, energy in the room shifts from cards.

Everything slows to a stop. Anthony parts the crowd. Too much time has passed since they last saw each other. They share a close embrace.

Iverson doesn’t work the room, but the room works him. Oladipo daps up and gets a photo. Paul and Wade, who both wear No. 3 in part because of Iverson, take a picture with three digits in the air. More people pay homage. The room starts spinning on its axis again.

“There are two people who have stopped Spades cold: Beyonce and Allen,” says Clarke Miyasaki, an executive at Stance. “When Beyonce showed, everyone wanted to look at her and say she was there. With Allen, though, everyone wanted to get time with him to show love.”

Thomas, preparing to appear in his first All-Star Game, was one of those people. The two diminutive guards had shared phone calls, but they had never met in person. Thomas used to razz Lee, his old rep at Reebok, about it so Lee was not going to miss the chance to link the two.

“He told me I reminded him of himself, that I was a killer,” says Thomas. “Once that happened, nobody could tell me anything about hoop. Those words, coming from his mouth, made me feel like the best player in the world. That changed my life—and he doesn’t know it.”

The conversation ended. Thomas walked back to Lee, eyes wide. Lee offered him a drink to calm down. Thomas would go on to have the best season-and-a-half of his career. Meanwhile Iverson, oblivious to the magnitude, sits down at a table and asks to get dealt into a game of Spades.

His career is long over, but Allen Iverson’s influence endures forever.

—

SLAM PRESENTS ’96 DRAFT IS AVAILABLE NOW.