Led by Guest Editor Carmelo Anthony, SLAM’s new magazine (below) focuses on social justice and activism as seen through the lens of basketball. 100 percent of proceeds will be donated to the Social Change Fund. Grab your copy here.

—

You have a chance in this life to make choices. The choice that I made was, I wanted to be on the right side of history. When people are oppressed, somebody has to stand up.

It was a blessing for me to be raised in the Hodges household, with a family that was politically and spiritually conscious and prided itself on commitment. Education was a premium and work ethic was primary. That was the foundation for me. Growing up in Chicago Heights, IL, during the 1960s, it was the tail end of Jim Crow. We were still struggling to get the rights that were necessary. There were boundary lines and rules that we were instructed to follow. We always walked in packs. I can recall not being able to sit at the lunch counter and watching white kids eat their sundaes, while I stayed attached to my mom at the hip.

My mom was a secretary for a civil rights organization in Chicago. I would sit between her and the president of the organization and watch real-life leadership unfold. As a young kid, I saw barriers being brought down.

I’ll never forget the day Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated. I was 8 years old. I had never seen my mom, grandmother or grandfather cry before. To see that, it put a fire in me to one day study and understand who that man was.

The truth is, my family shielded me from a lot of the racist things that were going on in Chicago Heights. I had a great childhood, but more importantly, it put me on a path to realize what the real bottom line is in this whole thing, and how the game is really played. When I went to Long Beach State, I looked back on my upbringing and could recognize the role that it played in the history of the larger movement.

The late Tex Winter, who was like a father to me, started recruiting me when I was a sophomore in high school to come to Northwestern University. I told him I wanted to go somewhere with warm weather, so when he got the job at Long Beach State, it was a blessing. He took me out there on a scholarship. My first college class was with Dr. Maulana Karenga, the founder of Kwanzaa, and from that point on my mission changed. The research and methods that I was taught at Long Beach State were about finding solutions to the conditions of Black people however I could, and to be well-rounded enough to listen and respectful enough to consider the impact that other cultures may have in solutions for our people.

Today, when I look at Stephen Jackson and his relationship to George Floyd, I understand it completely. I experienced it when I was 20 years old as a student. My close friend Ron Settles, a star on the football team who was bound for the NFL, got caught in the snares of racism and the wicked police force in Signal Hill, CA. He drove through a jurisdiction that didn’t like the success of a young Black man. He had a car that they felt he shouldn’t have. The police pulled him over and he was later found dead in his jail cell, having been severely beaten and choked. It lit an even greater fire under me. I don’t have the mega-reach of a Michael Jordan or an Oprah, but I do have my voice. I choose not to be silent about injustices. I choose not to be silent about the history of our ancestors and the sacrifices that they made so that we may be able to speak about these things today.

I had family members who studied sports and were politically mindful, so they always pointed to athletes who stood on the foundations of our people and who realized that you should never forget where you came from. John Carlos, Tommie Smith—those are my heroes. A lot of what they did in the 1960s, it planted seeds in me. As my career progressed, I recognized the magnitude of the stage that the National Basketball Association would give me. I knew, as I became a pro, that I’d have more of a platform than most of the community. I was taught to use it by watching people like Muhammad Ali, Jim Brown and Curt Flood.

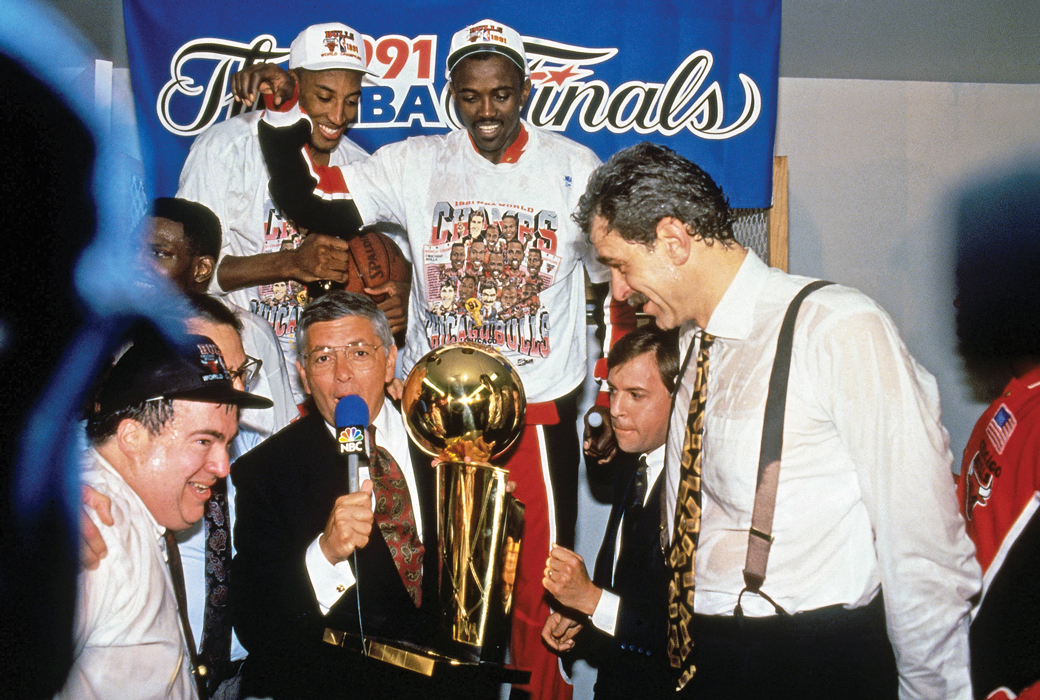

In 1991, I tried to convince my Chicago Bulls teammates and the opposing Los Angeles Lakers to boycott Game 1 of the NBA Finals. The precedent had been set when Jerry West and Elgin Baylor boycotted the All-Star Game until the League agreed to improve conditions for players. Twenty-one of the 24 players set to take the floor in the ’91 Finals were Black, but there was a lack of Black ownership in the NBA. Magic Johnson and Michael Jordan were probably the two most visible Black athletes on the planet at that time. We had a lot of power, particularly in the playoffs. But both Magic and Michael thought it was too extreme and my statements were dismissed, not even considering the critical thought in it.

My position had to do with the organizational structure of the League. We needed to get more Black ownership and Black management—people at the upper echelon of the game that looked like us, a problem that’s still being discussed today. The face of the game was Black, so why weren’t we more involved in the profit sharing? It was plantation politics.

Later that summer, I wore a dashiki and brought a letter with me when we made our celebratory visit to the White House after winning the ’91 championship. The night before we went, I was playing ping-pong with a good friend of mine and it just hit me: I can’t go there and say nothing. I was taught early on to write letters to councilmen. When I was 12 years old, I was writing letters to the mayor of Chicago Heights, directing attention to important problems. This was no different. I sat down and wrote an eight-page letter about discrimination in America and what the administration should be doing for Black communities.

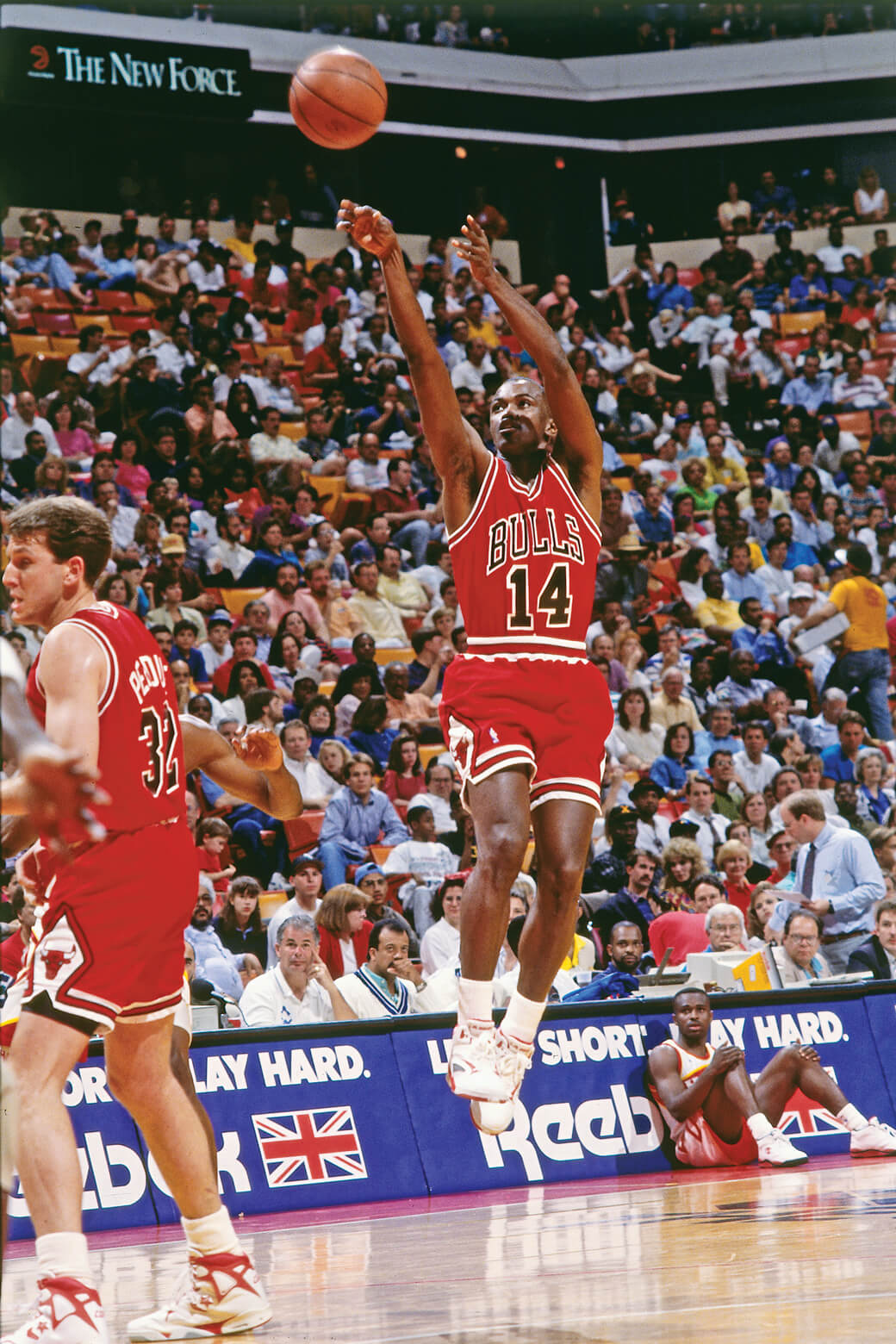

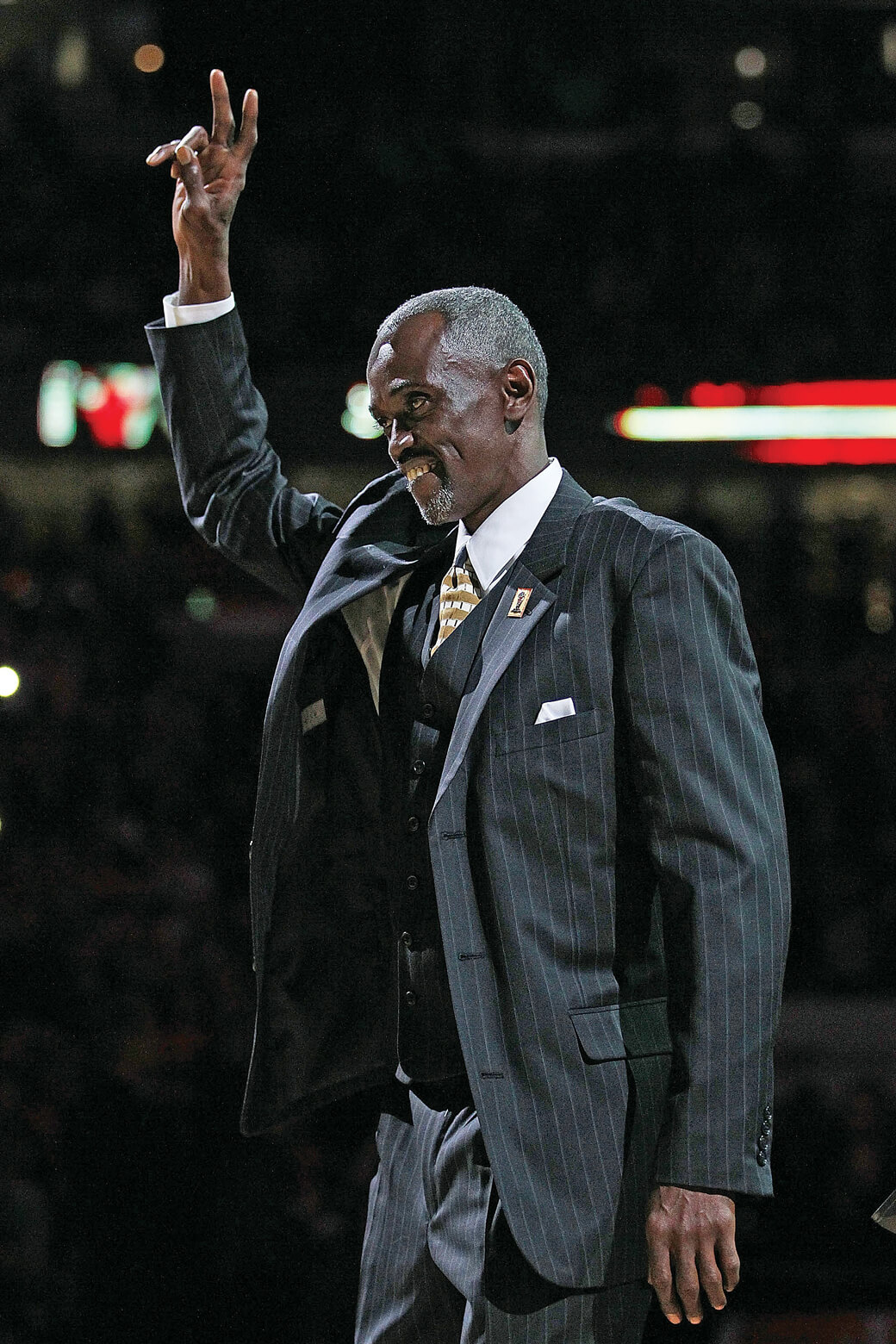

Actions like those led me to be blackballed from the NBA. After one more season in Chicago, which I missed due to injury, no teams would sign me or even offer me a tryout. I was a two-time champion and a career 40 percent three-point shooter. Go back historically. When MJ hit “The Shot” against Cleveland, I was starting in the backcourt with him. When we lost Game 5 against Detroit, MJ had 18 points and I had 19 points. I was the leading scorer for our team. The next season I was out because I had surgery, but you don’t lose your spot in the NBA or any other league because of an injury. You get a chance to come back when you’re healthy and regain that spot. I always played my role. I understood it was a team sport and never complained. But when it came time for me to get a contract, that wasn’t factored into the equation. That’s the way ownership operates. They want loyalty when they want you to be loyal. They want the players to be loyal.

To be honest, when I was blackballed, my union didn’t do much for me. I paid $30,000 in union dues and the best they could tell me was to find an agent that a team owes a favor to, who could convince owners that I’m not a “bad guy.” What does that even mean? I had never been fined. I had never missed a team plane. I had two world championships and three Three-Point Contest titles from All-Star Weekend. I need an agent to tell them that I’m not a bad guy? What did I do that was bad, NBA? What did I do that was bad that you could take away the wealth from my family? Wealth that I would’ve used to help change the condition of Black people in Chicago, to create programs and jobs. Maybe that was it. Maybe it was that they didn’t want me to shine, because if I shined in the city of Chicago, where I’m from, then I would’ve had an even larger platform.

Nobody wants to talk about how many Fortune 500 companies are still in existence from the enslavement of our people and they’re not paying us a dime back. I’m suggesting to all Black people in America, if you have any type of operations with those companies who have enslaved our people or aren’t doing business with us, we all should have a sit-down and not work. I’m asking all the players: Why are you going to hoop now? What are you going to play for? They’re killing Black people all over America. They have been. They killed my friend in 1981. They beat Rodney King in 1991. They’re killing people every day through police brutality. Colin Kaepernick sacrificed by taking a knee. I love him for being courageous. I love him for all the research that he’s done and is still doing.

We’re at a totally different point in history, and if you can’t feel it, there’s a problem with you. You’re stuck in the old paradigm. Right now, Black men in America have never had this much power. Never. We got too much power to play somebody else’s game. We have to think critically. This isn’t just me talking. I’m talking on behalf of my people who are suffering to this day all over the globe. We have to address the issues. They want the athletes to shut up and dribble. Shut up and dribble while people die. Don’t say anything. Take the money. Let’s stop and look.

We didn’t have social media in my playing days. If it had existed during the time Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf and myself were blackballed, there would’ve been an uproar considering how we shot the basketball. Social media is the game now. Everyone has a following. Use it. I applaud all the young brothers and sisters that are standing up.

To bring about real change, we have to define who we are. That’s the first thing. We have never done that. And we must let the world know who we are and this is what’s owed to us. Going forward, we have all the things that we need within us to create change.

With everything that’s going on, so many things are crystal clear to me because I’ve been honored to speak on these issues for my entire life. It’s a blessing, because we’re at the precipice of something that’s a lot larger than ourselves. It’s a beautiful time to be alive.

I have a voice. I made the choice to use it because this system has taken away and marginalized so many voices before me.

—

100 percent of proceeds from SLAM’s new issue will be donated to the Social Change Fund. Grab your copy here.

Photos via Getty.