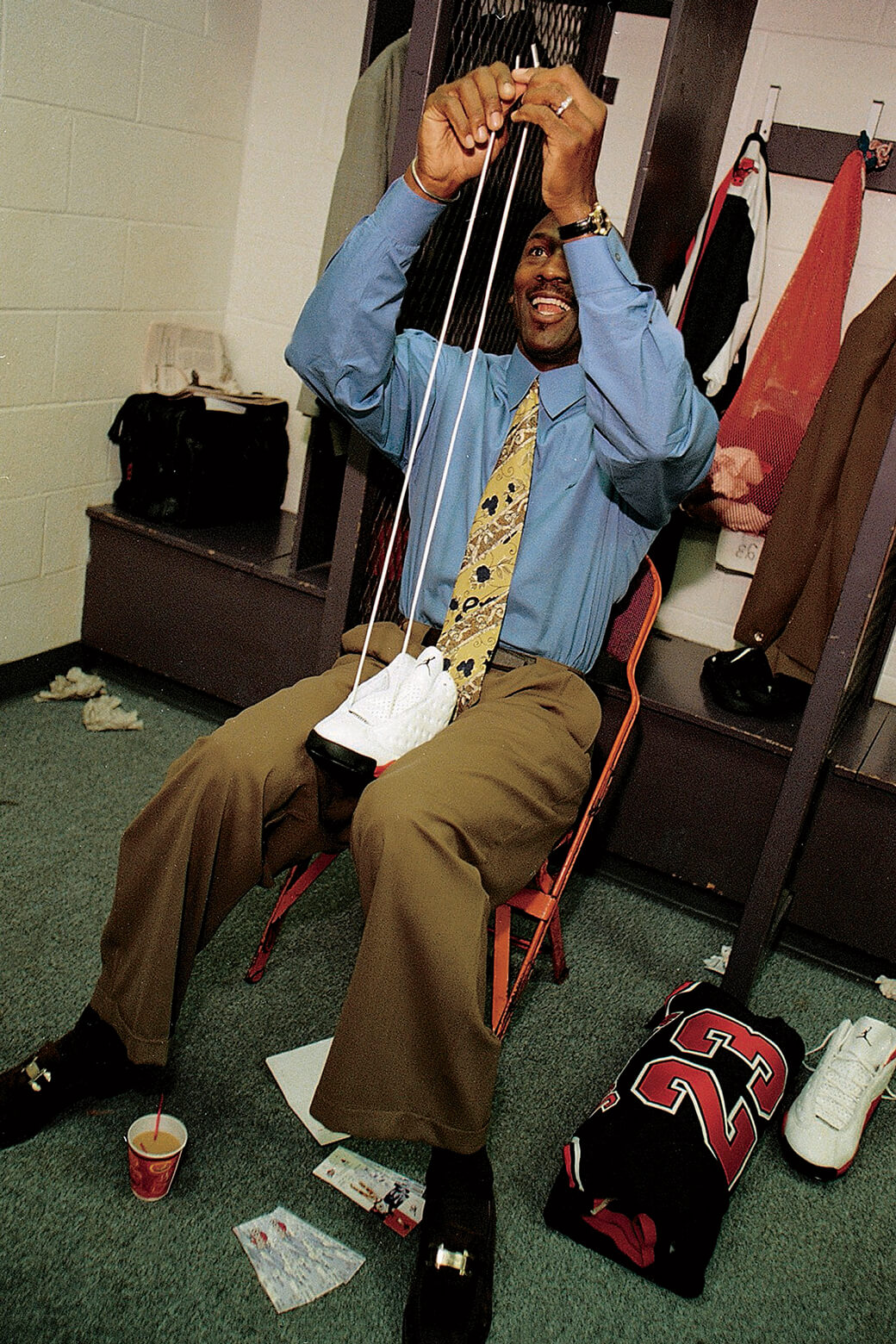

Photo above: Nicholas Griner.

GRAB YOUR COPY OF JORDANS VOL. 5

“I have no interest in going with Nike. I don’t even know what Nike is. No way I’m going.”

Those are the words that David Falk remembers Michael Jordan uttering to him when he approached MJ about hopping on a flight to Beaverton, OR, to meet with the sportswear brand to discuss an endorsement opportunity in the summer of 1984.

Falk, a 33-year-old sports agent at the time who had served as a junior agent for the legendary tennis star Arthur Ashe and had also repped No. 1 draft picks like John Lucas, Mark Aguirre and James Worthy at the ProServ sports agency, had arranged the meeting.

“He didn’t know anything about Nike. He wanted to go with adidas. He had a friend named Gary Stokan, who had played at NC State and was [now] the local adidas rep in the southeast. He supplied Michael with adidas,” recalls Falk. “He couldn’t wear them in the games because they were a Converse school—Carolina. But he loved adidas.”

ProServ actually had a really good relationship with adidas. The sports agency had become known for representing some of the biggest stars in tennis who also happened to be adidas endorsees, including Ashe and Stan Smith (who has one of the most famous signature sneakers of all time with adidas). The agency’s relationship with the German company, though, went deeper than just representing athletes who had deals with the Three Stripes.

“Ironically, we had represented the owner of adidas—named after Adi Dassler, who is the founder of the company. His son Horst Dassler had run the company for 15 years. Probably the most powerful man in the world of sports, and we actually represented him. I didn’t, but there was a gentleman in our firm that represented him,” recalls Falk, who aside from the aforementioned names, has also represented Patrick Ewing, John Stockton, Allen Iverson, Moses Malone and Dominique Wilkins, among many other NBA superstars. “They were just not in a position to execute a deal of that level—they told us that. The head of international marketing for adidas said to me, Hey, we really appreciate Michael’s interest. There is no way we could make this deal.”

As a result, an official meeting between adidas and Jordan never ended up happening, says Falk.

The agent had grown close with a few Nike executives over the years. At the time, adidas had Kareem Abdul-Jabbar while Converse had the likes of Dr. J, Larry Bird, Magic Johnson, Isiah Thomas and Aguirre. Although Nike was relatively new to the sportswear business, Falk had a few of his clients sign with the Swoosh in the years leading up to Jordan, including Moses Malone and Phil Ford. Falk had specifically developed a good relationship with Rob Strasser, who was the head of marketing for Nike at the time.

“So, I told Nike, Look, I think [MJ] can put you on the map in basketball single-handedly. He’s really exciting. Nobody knew he’d be as good as he is. But we all knew he’d be a very exciting player,” says Falk. “I told them, If you want to sign him, I want him treated like a tennis player. I want his own line of shoes and clothes. And they were open to that.

“We wanted to treat him like a tennis player. Tennis players and golfers typically use their own line of products. That’s the way it works in golf. That went against the grain of what everybody was thinking in 1984 in the NBA. Everybody thought that was a bad idea. Rod Thorn, who was the GM of the Bulls, said to me, ‘David, we love Michael, but if you try to treat him like a tennis player, you’re going to separate him out from the rest of the players.’ I said, ‘Exactly, because he is different than the rest of the players!’”

And so, while Falk had been able to talk Nike into considering giving Jordan his own line as a rookie, his new client didn’t seem to have any interest in a cross-country flight to the West Coast to meet with the brand. Frustrated, Falk went to Jordan’s parents to explain the situation and eventually got a Don’t worry, he’ll be on the plane, from the them. Jordan, forcibly, boarded a plane to Oregon.

At the meeting, Falk recalls Nike having prepared a music video-type presentation, featuring songs like “Jump” by The Point Sisters and “Jump” by Van Halen. But that was only after Nike execs struggled to get the video to play for what seemed like forever.

“The problem was that Strasser, who was about 6-3 and 350 pounds, could not get the machine to start. So, he’s sitting there and he’s trying to get the machine to start and it won’t start. And Michael is sitting there watching, not very happy. And Strasser is sweating like you wouldn’t believe. Like in the movies. He was sweating like a river,” recalls Falk. “There was only one African-American executive from Nike that was supposed to come to the meeting—it was Howard White, who ultimately became Michael’s service representative and who I had known for years; he was the point guard at Maryland before John Lucas. Howard shows up, like, 40 minutes late, and the machine isn’t working. You could have not scripted a worse start for an important meeting.”

“They finally got the video going. Michael never cracked a smile. Then we moved it to the boardroom and Strasser made a presentation about a line of shoes and clothes that would be Michael’s line. And he still didn’t crack a smile. And I know that when this is over, he’s going to curse me out for making him fly six hours to Oregon to sign with a company he didn’t want to be with.”

Falk and the Jordan family went to dinner afterward before their flight back to North Carolina. During casual conversation at the restaurant, Falk tried to get MJ to give his thoughts on the meeting. It was then when the super agent saw that the Tar Heel star had what it took to become the business mogul he has transitioned into today.

“He looks at me and goes, I don’t want to go anywhere else. This is it. I almost fainted. And I realized at that time, which was my first business meeting with Michael Jordan other than meeting to present our services, this man is really smart—for a 21-year-old young athlete, he kept all his emotions in check. He’s at the table playing a big stage game of poker, not letting on what he has. It blew me away. I was stunned.”

GRAB YOUR COPY OF JORDANS VOL. 5

Throughout the years that followed, Falk looked at his role as that of a teacher instead of an agent. He set out the mission of teaching MJ the business—teaching him how the game was played off the court. Not only was MJ receptive to the knowledge, he sought it out himself. Falk has countless stories of the times Jordan would come up to his office or hit his line inquiring about the strategy behind certain deals. And eventually Falk wasn’t the only one that MJ approached with those questions.

“He soaked it all in. That experience of managing his own brand as long as he played from 1984 to 1999—he met tons of corporate executives at very high levels, including Warren Buffett. I think that was all part of his ongoing business education. He took it very seriously,” says Falk. “On the investment side, he would sit down with the people in our office who managed his money and they’d give him a book that was an inch thick. He had studied that book and he would ask questions. Like, The return on this is supposed to be eight percent [but] looks like it’s only seven percent? It blew me away how prepared he was. But he took it all seriously because he’s a very intelligent person. He was very involved.”

The next three marketing deals after the Nike partnership were Chevrolet, Coca-Cola and McDonald’s. Although MJ was known for his ultra-assertiveness on the hardwood, in the boardroom his approach was a bit different, according to Falk. He was more of a poker player, showing no emotion. In many occasions, he didn’t really say much during meetings, says Falk. He’d listen. He was very analytical. He simply had a good sense of what he was looking for in partnerships.

Despite MJ’s status and Falk’s extensive network and relationships, landing marketing deals for NBA stars on a national scale back then wasn’t as prevalent and easy as it is today. There were still racial prejudices and stigmas that the League dealt with.

“[Back then,] no one had a brand in basketball. No one had any endorsements in basketball, basically. Magic Johnson—who had played five years in the NBA and was the Rookie of the Year, the [Finals] MVP as a rookie and an NBA champion—the only deal he had outside of Spalding and Converse shoes was a one-year deal with 7UP. One year and then it went away. Dr. J didn’t have deals. Bird didn’t have deals. Jabbar didn’t. Nobody had national deals because at the time, the feeling on Madison Avenue was that the NBA had two big problems—one, it was too black, and two, they thought it was too drug-infested. They estimated that 75 percent of the players were taking some sort of illegal drug. So it was not the darling of Madison Avenue that it is today.”

Just as influential as Falk and Jordan became in opening doors for NBA players through unprecedented off-court marketing opportunities, they also made waves by implementing clauses (or opt outs) in basketball contracts. They chose not to partake in the union’s group licensing program—betting on themselves that they could garner much more money doing their own marketing deals. They also added a unique clause in MJ’s first professional contract that allowed him to participate in competitive pick-up games during the offseason—which at the time wasn’t permitted.

“We did some very controversial things early in his career. We opted him out of the NBA Player Association group licensing program. Only two players in history have ever done that—Michael Jordan and Patrick Ewing—and then they changed the rule. We changed the contracts—created the Jordan ‘Love of the Game’ clause—that a player didn’t have to get permission to play basketball [during the] offseason. How do you stay in shape if you’re not playing? He had his own line of shoes and clothes. Almost everything we did, people said, You can’t do that; what you’re trying to do, it will never work. That’s what they told us with the shoes. You’re going to create a line of shoes for a rookie? It will never work! That’s what they told us,” recalls Falk. “And the first year Jordan sold $126 million worth of product. It outsold every other shoe company in basketball—as a rookie.”

It was then when Falk realized that they had built something historic by choosing to go with Nike through the golf player approach that ultimately allowed MJ to have his own line as a rookie. That’s something that rings truer today than could have ever been imagined back then.

“Jordan sells $3 billion worth of product a year. He sells more product that if you took every player in the League that has their own shoes, and you added up all the sales together and multiplied it by three, they don’t sell $3 billion,” says Falk. “If I could do it again, and I knew exactly what was going to happen, I would have signed him with Nike for a dollar a year and a 50-50 royalty [split]. But I wasn’t smart enough to know that we were going to sell—when Nike told me their projections for Jordan sales were $3 million, between three and four, and they sold $126 million the first year, you realize that the guarantee is irrelevant.”

—

GRAB YOUR COPY OF JORDANS VOL. 5

Franklyn Calle is a senior producer at SLAM. Follow him on Twitter @FrankieC7.

Photos via Getty.