Led by Guest Editor Carmelo Anthony, SLAM’s new magazine focuses on social justice and activism as seen through the lens of basketball. 100 percent of proceeds will be donated to charities supporting issues impacting the Black community. Grab your copy here.

—

Here’s an uncomfortable truth for those wondering why protestors are risking their health and lives to carry a hand-painted sign down a street lined with hostile armed police: Because every major advancement in social equality in the United States is the direct result of people taking to the streets to voice their grievances. The only reason most Americans are able to enjoy the weekend off, to go to the park for a pick-up game, to be compensated for a work injury, to have an education, to vote, is because someone, somewhere, got off their couch, cobbled together a crude sign, and waved it in the streets—usually while being beaten for their efforts.

Disagreeing with those in power is never met with beneficent approval and hearty handshakes but rather with blood, batons and bullets. In 1914 in Ludlow, CO, the tent encampment of 1,200 striking coal miners was attacked by the Colorado National Guard, killing many, among them 11 children. The chief owner of the mine, John D. Rockefeller—whose name is now monumentalized in libraries, parkways and plazas—is said to have ordered the attack. The blood-soaked results of what became known as the Ludlow Massacre, and other similar incidents of government-sponsored terrorism, is the 40-hour work week, reforms of child labor laws and safety rules to protect workers’ limbs and lives. The 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, during which Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, drew more than 200,000—the following year the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed. In 1913, 5,000 women, including Helen Keller, marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in support of women’s right to vote. They were met by a mob of angry men who injured 300 of the women while shouting insults and obscenities at them. Mansplained one of the mob, “There would be nothing like this happen if you would stay home.”

He was right. Nothing would happen if we all stayed quietly at home. Nothing would change.

If we’d all stayed quietly at home, there would be no Boston Tea Party and therefore no United States. If we’d all stayed home, we’d still have slavery and segregation. Women would still be incarcerated in the kitchen. LGBTQ people would have to remain hidden or face openly sanctioned violence. Laborers would work long hours for less pay under dangerous conditions. And police would be choking and shooting to death unarmed Black men and women without consequences.

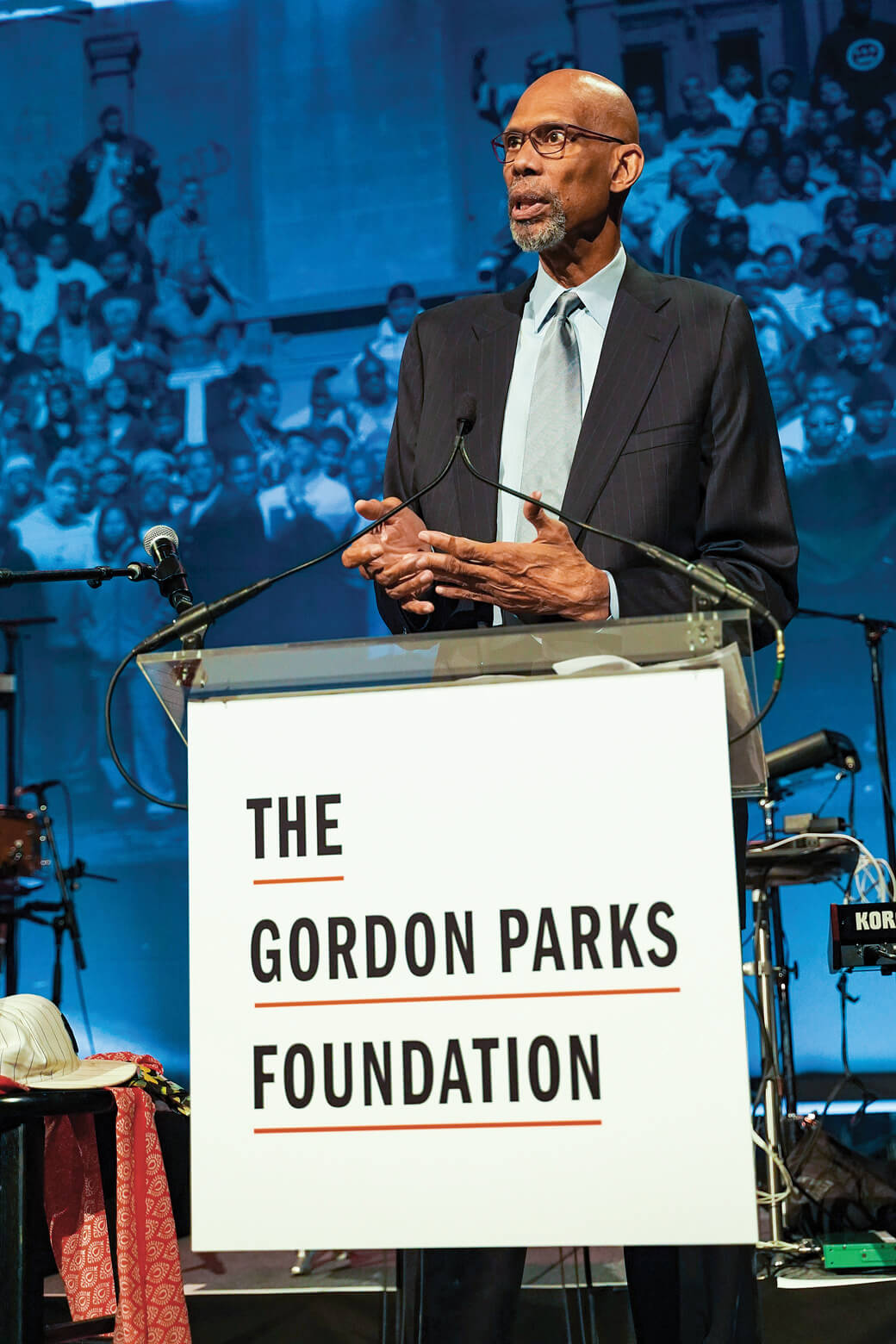

One of the most powerful and effective voices for change is that of the professional athlete. Certainly, they can take to the streets when they wish to fight injustice, but they also can take to social media and the press to reach millions of people with messages of defiance of status quo injustice and support for those risking everything to change things. The influence of the professional athlete is greater than it’s ever been. According to a Kaiser Family Foundation study, children ranked famous athletes second (73 percent) only to their parents (92 percent) among people they most admired.

Some athletes balk at the responsibility of being a role model to kids, stating they just want to play their sport and become rich. Well, like it or not, being a role model comes with the territory and athletes must decide what kind of model they intend to be or the press will decide for them. As we’ve seen during the last few weeks of this sudden social awakening, the public, corporations, businesses, entertainment conglomerates, and others, have magically become aware that racism exists and are firing CEOs, executives, actors, magazine editors and more for making racist, homophobic, and misogynist statements in interviews or tweets going back several years. Athletes have not been spared. The L.A. Galaxy fired soccer player Aleksandar Katai after his wife posted on Instagram what they called “racist and violent” comments.

I’m both grateful and frustrated at this frantic flurry of activity attempting to address systemic racism, especially among professional sports organizations. I’m always grateful when there’s more public awareness and therefore movement toward making substantive, measurable changes. But one always has to be skeptical of any sudden epiphanies that coincide with a bandwagon popularity because as soon as the megaphones are silent and the streets empty, outraged powerbrokers just as suddenly remember their bottom line and roll back their moral integrity as not cost-effective.

On June 5, NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell apologized for the NFL’s past insensitivity: “We, the National Football League, condemn racism and the systematic oppression of Black people. We, the National Football League, admit we were wrong for not listening to NFL players earlier and encourage all to speak out and peacefully protest. We, the National Football League, believe Black Lives Matter.” Then, in an ESPN interview, he said about Colin Kaepernick, who was deliberately driven out of football by Goodell and NFL owners who denied systemic racism, “If he wants to resume his career in the NFL, then obviously it’s gonna take a team to make that decision. I welcome that, support a club making that decision and encourage them to do that.” Pretty tepid support, especially considering the NFL’s website on May 22nd designated Kaepernick as “retired” even though he has made no such announcement. Kaepernick represents their past shame, which they would like to ignore.

Other sports organizations have also made the generic one-size-fits-all type statements that seem crafted more toward public relations than public welfare. While the NFL’s statement came five days after the death of George Floyd, the MLB waited nine days to state: “Our game has zero tolerance for racism and racial injustice. The reality that the Black community lives in fear or anxiety over racial discrimination, prejudice or violence is unacceptable. Addressing this issue requires action both within our sport and society. MLB is committed to engaging our communities to invoke change. We will take the necessary time, effort and collaboration to address symptoms of systemic racism, prejudice and injustice, but will be equally as focused on the root of the problem.” To which Black Mets pitcher Marcus Stroman replied, “Took long enough.” Individual NHL teams issued statements condemning racism, as did the NHL Coaches Association. Nice words from all. But why did it take George Floyd’s death to inspire this sudden woke attitude? Why wasn’t Eric Garner’s “I can’t breathe” in 2014 as appalling as George Floyd’s “I can’t breathe” in 2020? Or Michael Brown, 18, shot six times in 2014? Or Laquan McDonald, 17, shot 16 times in 2014 while walking away from police? Or the dozens of other unarmed Black men and women killed? These are the same sports organizations who were angrier at the athletes who kneeled to try to stop the killing than they were at the cops who did the killing.

In part, the past ire over protests is because sports organizations have often taken their cues from President Trump, the most overtly racist president in modern history. Believing that his cult of followers who worship the flag more than they do the Constitution are more important than the racism eroding the country allowed themselves to be bullied by his ranting tweets. This is the man who brags that “Nobody had ever heard of” Juneteenth, the celebration of the end of slavery in the US, before he made it famous. What he means by “nobody” is people who matter, i.e., white people. Because Black people have heard of it, but since we aren’t on his radar, we don’t count. Tone-deaf to the zeitgeist, on June 19 he proclaimed that if players kneeled in future NFL games, he wouldn’t watch. The question now is will the NFL forget their pledge to equality in the fall as if it were nothing more than a summer fling? And will other sports organizations follow?

The level of official how-much-we-give-a-crap-about-racism can be directly linked to the diversity in each sport. The NHL is 3 percent Black, the MLB is about 8 percent Black, the NFL 70 percent Black, and the NBA 80 percent Black. And though the NBA has not been perfect through the years in acknowledging and fighting racism, they have usually been the leaders in addressing the issue and in supporting their players speaking to their consciences. However, team statements after Floyd’s death have been decidedly “meh” given the intensity of the social climate. Only four—two written by Black coaches—acknowledge that Floyd was killed or murdered.

Some sports organizations are probably just hoping to ride out the public outrage until things return to some normalcy. For them, nothing will have changed. Others are having sincere discussions right now about how to address the issues in concrete ways that will improve the lives of people of color everywhere. Shortly after Floyd’s death, I was part of a roundtable discussion with NBA executives eager to embrace changes. I also sat with Lakers players and other members of the organization to hear what they had to say and discuss options for helping the community fight racism. The Lakers also hired UCLA assistant professor of African American Studies and Sociology Karida Brown as their first Director of Equity and Action to help the team aggressively combat racism.

And yet…

As hopeful as I am about the outpouring of public support against racism, my 60 years as an activist makes me cautious. When I was in high school, I got caught up in a racial protest in which I had to run for my life. It was July 18, 1964 and I had stepped off the subway to go to a Harlem record store to buy a jazz album. I noticed a rally protesting the shooting death of a 15-year-old African American, James Powell, by a white off-duty police officer, Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan. The shooting had occurred two days before, and there’d been protests throughout the city ever since. A thousand people had gathered outside the police station to express their anger. A police officer with a megaphone had tried to calm the situation by shouting, “Go home! Go home!” Someone in the crowd had shouted back, “We are home, baby!” Mayhem soon broke out. Fires were set, objects were thrown, shots were fired. I ran, crouched down—already feeling like a target because I was Black but also like an easy target because I was tall. Fifty-six years ago, they were protesting a white cop shooting a Black teen.

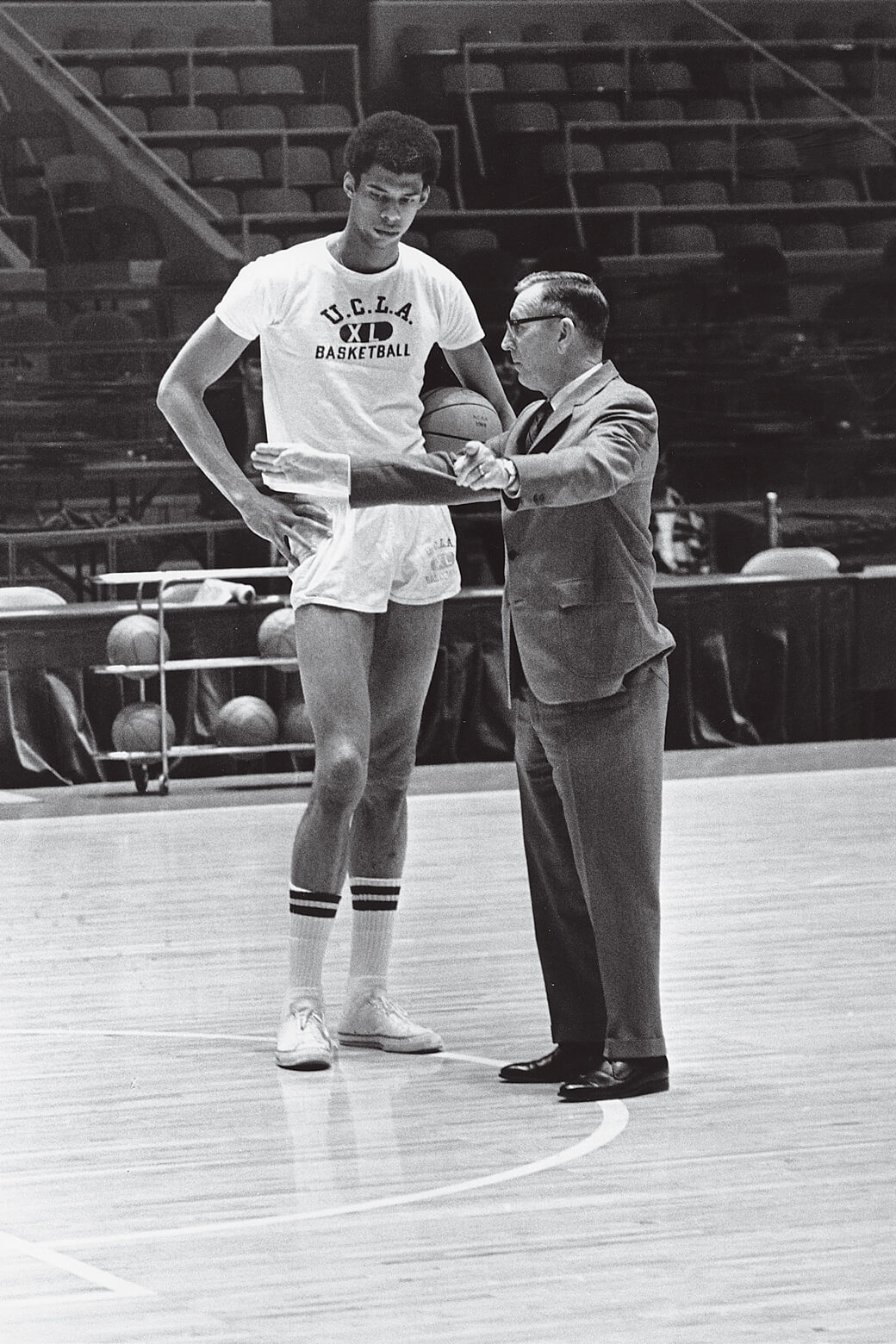

I began my role as activist-athlete shortly after that when I was at UCLA. At first, it was just a few on-campus rallies opposing the Vietnam War. My coach, John Wooden, did not encourage my activism and, though he didn’t overtly try to dissuade me, he made it clear that he felt it was a dangerous path for me to take. It took many years for him to finally come around and admit that I had done the right thing. Ironically, Coach Wooden was a social justice warrior long before it had a catchy term. In 1947, the basketball team he coached at Indiana State Teacher’s College won the Indiana Intercollegiate Conference title, which led to the National Association of Intercollegiate Basketball inviting his team to compete in their national tournament. But Wooden turned them down because the NAIB had a policy of banning Black players and Wooden refused to play without Clarence Walker, a Black member of his team. The following year, Wooden’s winning team was again invited to the NAIB tournament, after they had reversed their policy banning Black players. He’d risked his career, but his act of protest changed basketball.

He never told me about that when I was playing for him; he was too humble. Years later, when I found out what he’d done, I wondered why a man who’d put his career on the line for principle, couldn’t understand me wanting to do the same. I realized he was just trying to protect me from the backlash that he knew would be coming.

It came in 1967. I had achieved a certain amount of fame as part of the UCLA championship team. The press was very complimentary. I was still Lew Alcindor then, a nice wholesome American name (the name of the slaveholder who had owned my family), whose father was a decorated police officer. The press saw me as an icon of the “good Negro,” respectful to authority and grateful for being given an opportunity most Blacks would never get. But inside I was angry about the fact that other African Americans wouldn’t have the same educational opportunities. I just didn’t know the best way to express my anger.

Then, in May, I received an invitation from football great and Hollywood actor Jim Brown to join a group of Black athletes and activists in Cleveland to decide whether or not to support Muhammad Ali’s refusal to be drafted. At 20, I was the youngest and least experienced member of what became known as the Cleveland Summit. Ali was only 25 and he had to make the biggest decision of his life. If he allowed himself to be drafted, he would have had a safe, relatively easy two years in the service. If he fought the government, he would probably lose everything. But he was morally opposed to the war and didn’t want to be used as a recruitment poster boy to endorse the war. We vigorously debated Ali’s sincerity and commitment—a few of our group were ex-military—but in the end, we decided to support Ali. To witness Ali’s unwavering integrity, even as the government spent years trying to destroy him, was a turning point for me. How could I do any less?

How can any American do any less?

I realize that many white people are weary of hearing the protestations about systemic racism because it feels like they’re being accused personally, especially when they feel helpless to do anything substantial about it. It’s like having a sibling complain that Mom and Dad love you more. Even if it’s true, what can they do about it? First, don’t take it personally. Systemic racism has been rusting the engine of democracy long before they were alive. But acknowledging the overwhelming scientific proof that it exists and that it is destroying Black Americans is a step in fixing it. Second, support proposals that are aimed at eliminating racism. According to a Kaiser Family Foundation poll, 70 percent of Black Americans say they have experienced incidents of discrimination or police mistreatment. Let’s start there. By making Black people feel safer going for a drive, a walk, a jog.

The professional athlete today will be asked for their opinion on controversial issues and they must be prepared to comment intelligently and articulately. There is no more being neutral, because as South African activist Desmond Tutu said, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.”

—

100 percent of proceeds from SLAM’s new issue will be donated to charities supporting issues impacting the Black community. Grab your copy here.

Photos via Getty.