Legendary Canadian Streetball Collective, The Notic, Reunites Almost Two Decades Later

The world premiere of “Handle With Care: The Legend of The Notic Streetball Crew” is Friday, Oct. 8 at VIFF.

The court under the Cambie Street Bridge was probably the last place you’d expect to catch a glimpse of streetball royalty on this scorching July day in Vancouver, Canada. Luxury glass highrise condos encircled the court. Cyclists and middle-aged women with toy poodles passed back and forth along the adjacent promenade. On one hoop, a weekend warrior with a knee brace and AirPods plays solo, throwing up bricks.

But just off to the side, the band was getting back together. One by one, members of The Notic—the legendary Canadian streetball crew that dropped both defenders and jaws across Van City—started to trickle in. First it was Disaster; then came David Dazzle; then Johnny Blaze; then Delight, WhereYouAt and the rest of the crew. The daps, the jokes, the love were all captured by Kirk Thomas and Jeremy Schaulin-Rioux, the very same two-man film crew that had documented them nearly two decades earlier.

Last to arrive on the scene was and is the mightiest baller of them all: King Handles. Yes, the King Handles.

“Oh, look at this guy!” hollers Johnny Blaze, aka Jonathan Mubanda, as King Handles was spotted on the horizon.

Walking up with swagger, dripped out in his own KH clothing line, King Handles flashed his Magic Johnson-watt smile as the crew embraced him like they were at their 20-year high school reunion. Mid-handshake, King Handles, aka Joey Haywood, quickly sized up a now grown Disaster, aka Rory Grace (the youngest of the crew and the sole white player), and let nostalgia get the best of him.

“Hey, we gonna play one-on-one or what?”

“Sure man, let’s go!”

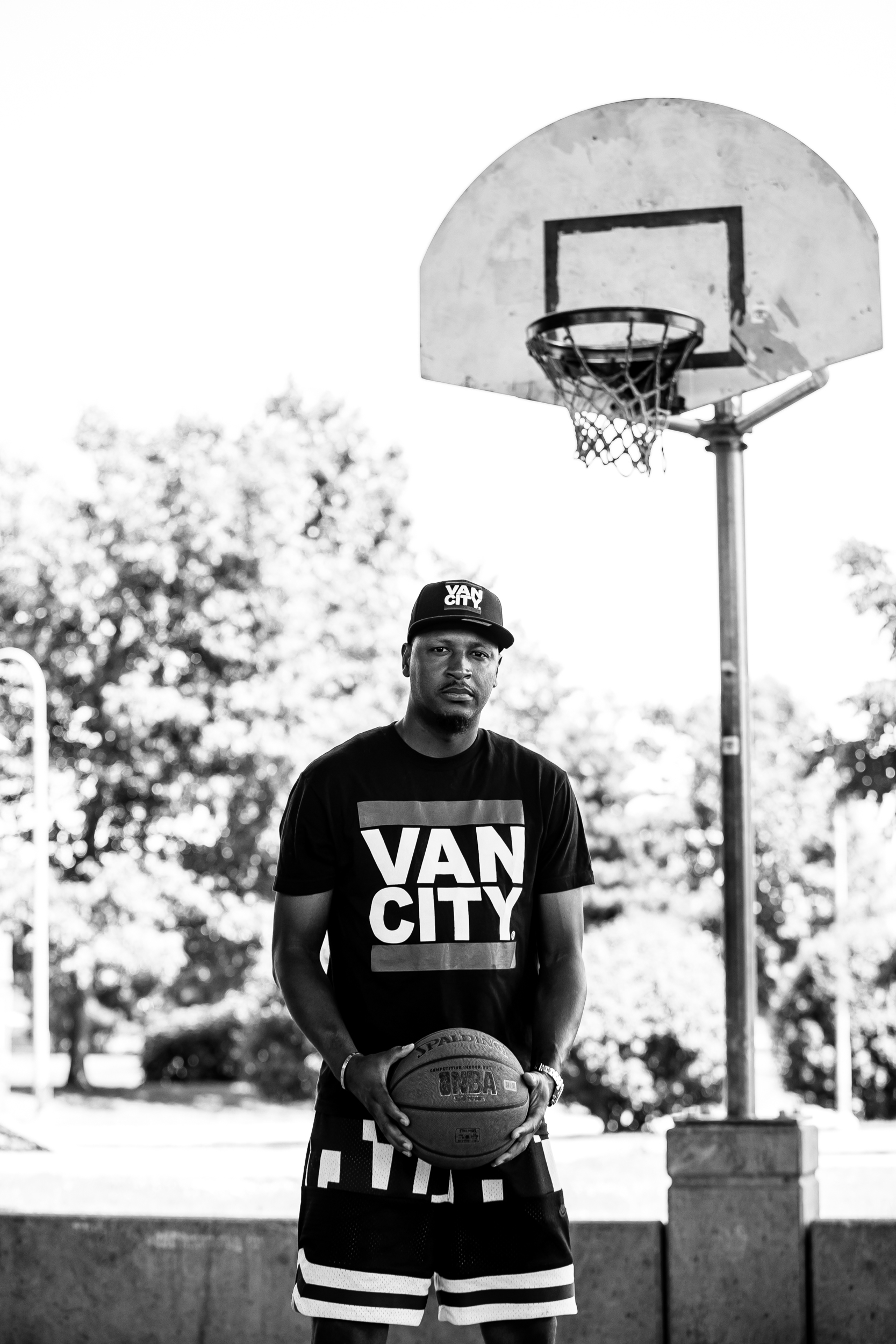

Joey “King Handles” Haywood and Rory “Disaster” Grace

Sixteen years ago, this very same playground served as the backdrop to one of The Notic’s defining moments. After two successful mixtapes—The Notic and The Notic 2—showed them doing shit even the AND1 cats weren’t doing, the world started to take notice.

In 2005, SLAM ventured up North to profile The Notic in SLAM Presents Streetball, Vol. 3. The story included an iconic pictorial under the Cambie Street Bridge with Vancouver’s signature grey skies. The shot now looks like a time capsule, as half a dozen members were draped in baggy fits, rocking 2000s era brands like Sean John and Enyce.

Even though they wore scowls in the photo, The Notic proudly basked in their newfound fame. They cleared every issue from 7-11 shelves. They signed a few autographs and stunted around town. They reveled in the thought that people in New York, Tokyo and Paris read about them and knew their names.

“If you ain’t never been in SLAM, you never made it,” declares Johnny Blaze matter-of-factly, as the impromptu one-on-one game between King Handles and Disaster played out in the background.

“To get validation from SLAM? That doesn’t happen out here,” adds Blaze’s brother David Mubanda, aka David Dazzle.

Jonathan “Johnny Blaze” Mubanda

David “Dazzle” Mubanda

The reunion was being filmed for an upcoming documentary about The Notic that’s slated to premiere at the Vancouver International Film Festival in October. As the crew posed to recreate that iconic SLAM picture, their clothes were more fitted and the boys were now men. Most of their basketball careers were long in the rearview, but they came together a final time to complete their mixtape trilogy and tell the world their story, about how a group of misfits created a style of basketball that was unseen at the time in Canada and beyond. And has not been seen since.

It started at Hoop It Up.

The year was 2001, and the famed three-on-three global tournament was being hosted at Vancouver’s Science World. With cameras in tow, two friends and amateur filmmakers, Thomas and Schaulin-Rioux, were filming a random game for fun when they noticed a rowdy crowd forming around a neighboring court.

“And then we went over and saw Joey’s game,” says Thomas. “It was nothing like we had ever seen before in Vancouver and immediately knew that we stumbled upon something special.”

Jeremy Schaulin-Rioux and Kirk Thomas

There they were, a group of teenagers with flair, putting on an exhibition with ridiculous handles and dimes. There was Goosebumps, drawing oohs with an inventive backhanded dribble; King Handles hitting helpless defenders with lightning quick, five-dribble combos as if he were a golden gloves boxer; Dazzle mesmerizing the crowd with his drunken master style of dribbling. The Notic would get the Rucker Park treatment, with fans rushing the court whenever they went SportsCenter on their opponents.

“We just had this synergy whenever we played together,” says Mohammed Wenn, aka Goosebumps. “We liked to play to the crowd, because we never really got that attention playing in our high school games.”

“It was just the fun of playing with your friends because we all went to different high schools around Vancouver,” adds Jermaine “J-Fresh” Foster, who had handles and could occasionally put you on a poster. “Honestly, we felt like little rock stars.”

Even with exposure to the NBA in Van City (the Grizzlies were still in town), the style of basketball in local high school and college gyms was conservative. Coaches wanted fundamentals over flash. Members of The Notic, who were mostly first-generation Canadians and immigrants, emulated the Shammgods, the Iversons and the Skips. They were outcasts in traditional, let’s call it what it is, “white” basketball circles. The perception of them and their style had racial undertones. One youth coach told King Handles to drop the “jungle ball.”

But collectively, they found acceptance and brotherhood. “When we got together, we had no coaches, nobody telling us what to do,” says King Handles. “We could be who we were.”

“We felt basketball coaches rejected us, so we kind of said, To hell with that, and did our own thing,” Goosebumps adds.

Ryan Akinkeyin

Mohammed “Goosebumps” Wenn

Weeks after Hoop It Up, Schaulin-Rioux and Thomas introduced themselves to the crew at the Whalley Rec Centre. The Notic, who in actuality were much larger than the Hoop It Up squad, agreed to be documented. Influenced by ’90s underground skateboarding videos, the filmmakers had each baller conduct a solo spot.

“They each took a turn freestyling, almost like a DJ battle,” says Schaulin-Rioux. “And then, all of a sudden, we’re seeing these guys do [moves] with these handles that we’d never seen anyone do, not even the AND1 guys.”

Mixing the freestyle shoots with compiled grainy open run footage, the producers decorated the mixtape with underground hip-hop tracks from artists like Jurassic 5, graffiti text overlays and clever graphics, packaged into old Blockbuster Video cases. The Notic was created in 2001. The uber-popular sequel, The Notic 2, was released a few years later with harder music and more sophisticated moves. Since it was the early 2000s, Thomas and Schaulin-Rioux marketed the trailer on streetball message boards online. It wasn’t long until they were receiving money orders for the VHS mixtape from Poland to Japan and all over the world.

“Social media didn’t even exist back then. It’s crazy to think what could have been if there was that avenue to get it out there,” says Disaster.

Their legend only grew when the mainstream got word. When the AND1 Mixtape Tour made a stop in nearby Seattle in ’02, The Notic didn’t waste the opportunity. Disaster, who was 15 at the time, looked like a cross between Jason “White Chocolate” Williams and Lil Bow Wow as he danced with the rock, nutmegging defenders repeatedly while ESPN cameras rolled. Clips of King Handles crossing up Headache instantly elevated The Notic’s credibility.

“I knew from that point we could take our talent around the world and hold our own against anyone,” King Handles says.

But just because they could hang with the AND1 guys didn’t mean they were getting paid like them. In that era, Canadians were still overlooked and largely kept up North. Even around the time of the SLAM feature, the members were starting to move on from streetball. They were getting older, bills had to be paid, and soon they would be starting families and real 9-5 careers.

“It was all a dream!” Dazzle says in his best Biggie voice, reminiscing about The Notic’s peak.

And then, it just faded away.

After all the notoriety King Handles gained from streetball fizzled, he shelved his playground persona and transitioned to organized hoops. He balled out at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, leading the nation in scoring in 2011 before embarking on a decade-long basketball odyssey, bouncing around second tier pro leagues in Canada, Denmark and Iceland. Through a chance invite to a three-on-three tournament in Japan in 2016, where The Notic legacy is strong, his fire for streetball was reignited. Shortly after, his Instagram blew up and King Handles was able to gain a cult following half a world away in Asia.

Much of King Handles’ second act was captured by his childhood friend and filmmaker, Ryan Sidhoo, who has made a pair of short documentaries about the playground legend.

When Sidhoo was creating those docs, he had gone to Schaulin-Rioux and Thomas for archival footage. When the trio finally met in person at a three-on-three tournament in Toronto in 2019, the idea of collaborating on a revival project on The Notic gained momentum.

“The Notic really changed my life, and I’m so proud of those tapes and that crew, but I always look back with regret that it died out unfinished,” says Schaulin-Rioux. “For Kirk and I, finishing this story feels like a weight lifting off those memories, and what’s left is just the moves, the tapes and especially the brotherhood.”

The film will also focus on the long-awaited completion of The Notic 3, the final installment in the trilogy. Schaulin-Rioux has hours of unreleased footage—both from the early days and an unreleased documentary he shot of King Handles in ’07, when Haywood first embarked on his pro basketball career.

“If you take basketball out of it, you have a group of outcasts and misfits who went on to leave their mark and legacy, not only on their sport, but also the culture of a city,” says Sidhoo, the producer of the upcoming documentary. “It’s beautiful that they’re still being celebrated years later.”

Reuniting The Notic was not exactly as complicated as the Fresh Prince reunion special. There is no bad blood, and most of the members are still connected. Many have families and flourishing second careers now. Andrew “6Fingaz” Liew, who had Stephen Curry-type range (and yes, six fingers on his left shooting hand) owns a successful construction and design company. J-Fresh is a popular, local hip-hop DJ who has spun in major clubs in Brazil and L.A. The brothers, Dazzle and Blaze, are renaissance men dabbling in real estate and community work.

Andrew “6 Fingaz” Liew

Jamal “Where You At?” Parker

Dauphin “Delight” Ngongo

Jermaine “Fresh” Foster

And of course, there’s King Handles, who has managed to stay relevant in the streetball world and works as a basketball trainer. But instead of hate or jealousy from his crew, there is nothing but love and appreciation. Again, this is family.

“The thing about King is he kept us alive, kept reppin’ us in whatever he did,” says Blaze. “He doesn’t have to do it, but that is who he is. But that’s all of us though. We represent each other everywhere we go and we help each other even to this day.”

For as beloved as King Handles is today and how much The Notic’s name still rings bells around Vancouver, they were probably ahead of their time. Maybe if Instagram and YouTube were around back then, or Canadian basketball players were as respected as they are now, there might have been more college scholarships, sponsorship opportunities or even the NBA in King Handles’ case.

But the film chooses to focus on the what was versus the what ifs. At its core, this is a human story that gives flowers to the underdogs.

“We were young legends,” concludes Goosebumps. “We were so raw and spontaneous and when we came together, we were this unstoppable force.”

Portraits Patrick Giang/Victory Creative Group.