Ted St. Martin doesn’t shoot free throws anymore.

The basketball court was a sanctuary for St. Martin, but his body won’t let him do what he did arguably better than anyone. He could try to shoot, but his tired knees deter him.

Foul shooting was St. Martin’s area of expertise. He made one of the slowest aspects of the game compelling. His legend grew with each stop on his circuitous journey across the country. The games and exhibitions may have been ugly at times, but his halftime specialty made the sport feel pure with each swish. It was an era of dominance defined by a single shot, then another, and several more with the same result.

It is worth noting that St. Martin just turned 80 years old earlier this year.

The Jacksonville (FL) resident holds one of the most remarkable shooting records in the history of basketball. In 1996, he made 5,221 consecutive free throws, setting a Guinness World Record. The exhibition took more than seven hours to complete. St. Martin had wrapped up a shooting clinic on his home basketball court that day, before launching into a free throw bonanza.

“The shot that I’ve got is so mechanical,” says St. Martin recalling that April afternoon. “I just kept my mind on what I was doing. That’s always what I did when I was shooting baskets.”

Before basketball, farming was the focal point of St. Martin’s life. His parents, seven brothers and five sisters grew up on a dairy farm in Yakima (WA), located more than two hours southeast of Seattle. As a freshman in high school, St. Martin’s basketball coach introduced him to his first free-throw shooting style. Players were expected to shoot underhanded. In one practice, St. Martin says he sank 30 straight shots underhanded—with one and two hands, respectively. He didn’t shoot much in games. In fact, St. Martin did his damage without the ball, spearheading the team’s 1-2-2 press as a backup guard.

“I chased the ball,” St. Martin says. “I loved to play defense. I always had an interest in shooting free throws, though.”

St. Martin moved to Riverdale (CA) to work on another farm into his early 30s. He played for city league teams, but was never a prolific scorer. One day, he nailed a hoop to the dairy barn. Fascinated with his free throws, he started shooting. The first 10 shots connected, but that was merely a warm up.

“I made 210 in a row,” St. Martin says. “Then I missed one, and made 514 more. I wondered what the record was. At the time, it was 144. So, I started pursuing the record officially.”

Every week, St. Martin entered the gym, and went straight to the line. With a gym full of witnesses, St. Martin set a new record in 1972 with 200 consecutive free throws made. The subsequent world records he set were staggering:

305. 315. 386. 927. 1,238. 1,704. 2,036.

The free throw changed St. Martin’s life. He was hired by AMF Voit to perform at clinics and sport shows. Asics and adidas became sponsors for his exhibitions. He was named an honorary member of the Phoenix Suns in the 1970s. Schools, shopping centers, car dealerships called for the foul-shooting ace. He even made a stop at the local YMCA in my hometown of Watertown (NY) for a shooting clinic in the summer of 1990.

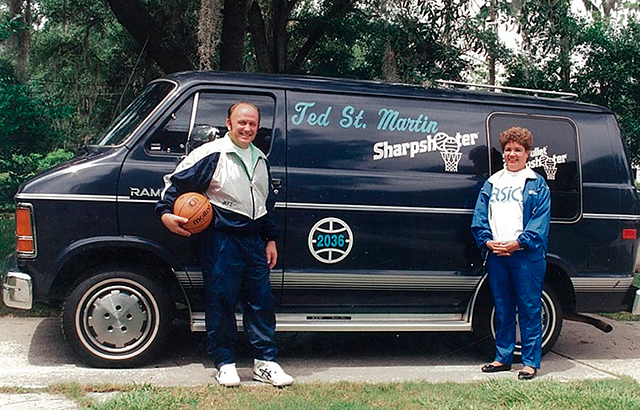

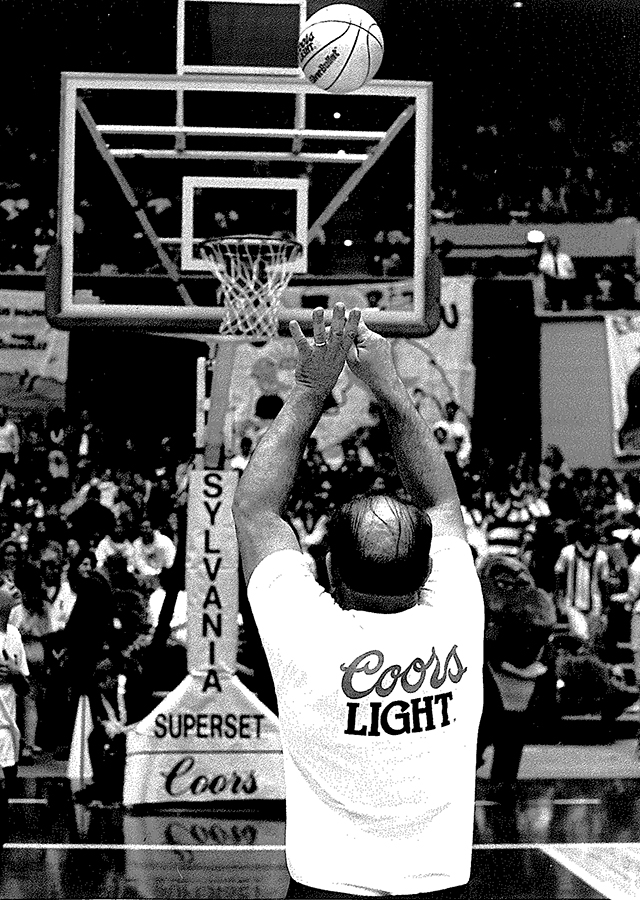

The final sponsor was Coors, and St. Martin was labeled the “Silver Bullet Sharpshooter.” The company provided him with a traveling van, which he drove to every show and commitment. His second wife, Barbara, came along for the ride. Truck drivers wouldn’t be envious of the miles they logged. Yet, at every basketball arena, halftime belonged to Ted.

“In time, people stayed in the stands to see if I would miss,” St. Martin says. “People would hold up pictures of scantily clad women. I didn’t want to miss, especially with my wife there. When I missed, the crowd roared like they won the basketball game.”

How far did St. Martin’s fame reach? He became good friends with Rick Barry and Bill Sharman—two of the NBA’s greatest free-throw shooters. John Havlicek visited St. Martin in his van once to talk about the game. One year, St. Martin says he was invited to the Hall of Fame in Springfield, MA to face Calvin Murphy in a foul shooting contest. Murphy boasted an 89 percent career average from the charity stripe. The former Houston star declined to participate, but Hall-of-Famer Dolph Schayes filled in admirably for Murphy. The opponent didn’t matter. The final result still favored St. Martin.

There were no secrets to St. Martin’s shooting. Former LSU basketball coach Dale Brown felt St. Martin could solve his star center’s free-throw futility. Shaquille O’Neal was a 58 percent shooter from the line during his three years in Baton Rouge. Brown was unable to have St. Martin tutor the All-American big man due to NCAA bylaws.

“Shaquille would’ve been receptive,” Brown says. “He was a tender, gentle and sensitive guy. Watching Ted would’ve been good for him. [Ted] wasn’t an elite athlete. He just had a funny style, just to show you practice doesn’t make perfect. Perfect practice makes perfect.”

Prior to the NCAA’s ruling, St. Martin spent one practice with players at Jacksonville University. They were the worst free-throwing shooting team in the Sun Belt Conference. By the end of practice, each player finished above 70 percent for the day. The squad lifted its team percentage from around 50 percent to 70 percent by season’s end.

St. Martin felt great joy in coaching. He would conduct clinics at home in Jacksonville and on the road. He never got the chance to mentor O’Neal, but he thinks that there could be a place for his expertise in the NBA.

“I’d love the opportunity to work with NBA players,” St. Martin says. “Whether it’s Dwight Howard, LeBron James, any of those guys. Anyone who shoots 75 percent or lower, I’d love to work with them. I’d get them to 90 percent. It wouldn’t be much. Might be a slight bend of the knees or a nice follow-through. That’s all it takes. I could get them to 90 percent, guaranteed.”

The students he taught on April 28, 1996 were believers of St. Martin’s shooting acumen. The act of convincing them took longer than an afternoon, but they could testify to history. Five thousand, two hundred and twenty-one consecutive makes from 15 feet. St. Martin was automatic for more than seven hours.

“I knew I was near the record,” St. Martin says. “I just wanted to keep shooting. I had already beaten the record once before. After that, the pressure was off. We had a man keeping track, just counting five at a time. I remember it was on a legal pad, and boy was it messy. It was covered top to bottom.”

When players approach the free-throw line, the cognitive part of the brain switches into the routine. One dribble. Three dribbles. Spin the ball once, or maybe twice. One dribble to the side. Wipe sweaty fingertips on the shorts. Pay homage to a loved one by touching the tattoo on the left or right arm. Gently rub the face, or blow a kiss to the rim, to say hi to the spouse and kids watching on television. Whisper words only the shooter can hear. Every NBA player uses a routine to find their rhythm.

St. Martin doesn’t spare a second. He catches the ball, brings it to his chest, and releases a two-handed set shot starting at his chin. His left guide hand opens up and his fingertips flash outward, which many would assume blocks his vision on the release. But who are we to critique? The man owns Guinness World Records.

That’s right, there are others. The free-throw record isn’t even St. Martin’s favorite.

“My favorite of all-time is making 84 shots in 8 minutes from 30 feet out,” St. Martin says. “I did this at a sporting goods store in Orange, CA. That might be the hardest one to break.”

St. Martin’s feats have inspired others across the country. The best example may be Bob Fisher, who lives in a small town in Northeast Kansas. Coaching basketball was just a hobby to Fisher. For more than 20 years, he’s studied the science of shooting. He analyzes how physics and anatomy are important variables behind made baskets. He studied medical journals and developed launch devices to assist with consistent shooting. The education from St. Martin may have been the greatest lesson of all.

“I met with Ted on the court in his backyard,” Fisher says. “I told him I was planning on going after a record. He gave me a good pep talk. What really struck me was that this guy is just an ordinary guy. If he’s ordinary, then I am ordinary. I can set a record, too.”

Five years ago, Fisher set his first Guinness World Record, making 50 free throws in 60 seconds. He established new world marks in 13 other categories. One of the most impressive 30-second records is connecting on 21 of 24 shots without looking at the hoop (he was blindfolded, of course).

“The fact is that it’s doable for everybody,” says Fisher, now 57. “You can be good in whatever you want to be. Ted is an example of that.”

Records are broken every day. Brown believes St. Martin’s free-throw mark will be untouchable.

“There is no comparison here,” Brown says. “Peter Maravich averaged 44.2 points per game at LSU. Today, you can tell a recruit if they want to break that mark, all they have to do is make 15 3-pointers a game for four years. It’s not going to happen.

“No one will ever win 10 NCAA men’s basketball championships. It will never be broken. Ted St. Martin’s record? No way.”

There was another important milestone number St. Martin wanted to reach. His plan was to shoot hoops until he was 70 years old. That benchmark was as easy to reach as his 15-footer was to make. He wrote two editions of his book, The Art of Shooting Baskets, which included forewords by Hall-of-Famers Barry and Sharman. He also created The Winning Shot DVD that walks through the steps of becoming a 90-percent free-throw shooter.

St. Martin no longer competes, and his home court in Jacksonville is quieter these days. Parents with eager children still approach him for a tutorial, hoping the kids can perfect their jumpers. Young shooters may see an increase in their efficiency.

None will likely experience a life that runs parallel to St. Martin’s. An unorthodox shot leading to an unbelievable record.