In 1985, it arrived.

The Air Jordan I, the sneaker that changed the world. Premium leather stitched to a cup sole that sat on top of a Nike Air bag.

The shoe was made for basketball. But it’s an art piece now, a symbol that represents so much. Youth. History. Style. Innovation. Community. Winning.

It’s been 33 years since the I dropped for $65. Thirty-three years since its spot at the top became unquestionable.

How did it happen? How did the I become the silhouette that ignited an entire way of life, that allowed so many people to fall in love with sneakers and with basketball?

The journey begins in Beaverton, OR, at the Nike World Headquarters in 1984. Phil Knight was set to go all-in on one player from the ’84 draft. There were five future Hall of Famers in that class (big shout out to Oscar Schmidt). Knight wanted to go after Hakeem Olajuwon, Charles Barkley, John Stockton, Sam Bowie or Michael Jordan.

He tasked Sonny Vaccaro, at the time an executive at Nike, with determining who that player would be. Vaccaro was watching in 1982 when Jordan hit that game-winner against Georgetown to capture the National Championship. MJ caught the eyes of the nation that night, offering a glimpse of the brilliance he was going to bring to the court. And now he was on Sonny’s radar.

Vaccaro had been around the game for years by that point. He orchestrated the groundbreaking sneaker contracts between Nike and the Big East colleges. He co-founded the Dapper Dan Roundball Classic, a high school all-star game that ran in Vaccaro’s native Pittsburgh. Vaccaro knew just about every young hooper in the nation, except for the kids Knight was targeting in the draft.

“Tony Roma’s,” Vaccaro says, looking back at the first time he met Jordan in Santa Monica in 1984.

“Other guys had shoes,” Vaccaro says. “Magic had a shoe, Dr. J had a shoe, Walt Frazier. This was going to be a shoe and there would be no other shoes for this athlete. He was going to wear this new line. Air Jordan. That’s what made Michael want to have a second meeting. He said, What do you mean?”

Jordan never messed with Nike before that meeting. He had worn Converse at UNC. He was a huge fan of adidas and had every intention of signing with the Three Stripes.

Vaccaro was able to set up another sit-down with Jordan, even with the deck stacked against Nike. This time, MJ’s parents went with him to Oregon. Knight, in a rare move, was waiting for them. He wasn’t often involved in those types of get-togethers. Rob Strasser and Peter Moore were there with Vaccaro. Strasser served as VP for the Swoosh, Knight’s trusted public voice, and he was close with Jordan’s agent, David Falk. Moore was the lead designer on the line.

“We showed him some rough sketches in the famous meeting when he came out,” Moore says. “I was designing the shoe with the idea that I needed a real basketball shoe that the best basketball player in the world could play in. But I also needed something that would be unique, never seen before.”

Moore unveiled the design while Vaccaro shared the vision. He detailed how Jordan would become a partner with Nike, receiving unheard of royalties for each pair sold. He would have creative control. He’d be the face of the brand.

“The whole concept was to have a home shoe and an away shoe, which is now much more common,” Moore says in Peter Moore: A Portfolio, a book about his work. “Back then, it was a whole new way of doing things. Rob’s point was, if you were going to have a shoe for sale, why not have two?

“Rob wanted to change the way athletes were marketed,” Moore continues. Strasser and Falk both agreed that Jordan should be presented to the public as an individual, which was rare for an athlete in a team sport.

“It sounds so simple, so obvious,” Moore notes. “But at the time it honestly broke all the rules for how our industry operated. Nobody had taken a player, created shoes and apparel that tied to his style, then launched it all once.”

Jordan has admitted before that he was too young at the time to realize the opportunity. He wasn’t able to comprehend everything that Nike was offering because, in truth, he only wanted to sign with adidas. It was Deloris and James Jordan who pushed him to give Nike a real look, in part because of Vaccaro.

“I was honored that I was able to connect with the Jordan family,” Vaccaro says. “They took me into their lives. They trusted me.”

That belief in Vaccaro didn’t exactly translate to faith in Moore’s initial designs.

“The idea was to break the color barrier in footwear,” Moore remembers. “Prior to that, 99 percent of shoes were white or black, so I decided to design a shoe that would really take color well. And the colors were red, black and white. I didn’t pick those colors. That’s the colors of the Chicago franchise. We did a bunch of color-ups, like a coloring book. I showed him a whole bunch of those pages. At first he was very leery of red, black and white. He did not like those, as has been quoted. He called them ‘the Devil’s colors.’ He wanted to wear Carolina blue. I told him, you’re gonna have to talk to the guy that owns the Bulls.”

Jordan’s insane competitiveness, the desire that led him to six championships, had a tendency to run into a level of stubbornness at times. He still wasn’t feeling the Nike silhouette and he made one big request to Moore.

“He was very afraid of Air because he envisioned it as making the shoes much higher off the ground,” Moore says. “He didn’t want to be high off the ground because that’s going to cause an ankle sprain. He wanted a shoe low to the floor so he could feel the floor. We did that. We took a lot of the cushioning out of the shoe.”

Moore has said that the actual design of the I is “rudimentary.” Looking back now, that may be the case when compared to the performance beasts that Jordan Brand puts out now. But even if the sneaker’s construction was elemental, the parts all worked together in concert beautifully.

With a simplified Air bag inside of a rubber midsole, the sneaker’s premium leather upper was given the spotlight. Michael loved adidas so much because their shoes felt worn-in the moment he took them out of the box. The leather was Moore’s response to that, a way to give the I as much comfort as possible.

The sneaker was then rounded out with a perforated toebox and a new traction pattern.

But because his first signature wasn’t ready for the start of the regular season, Jordan spent a good chunk of time playing in the Nike Air Ship, which looks similar to the I. That was the silhouette that the NBA banned, saying, “The National Basketball Association’s rules and procedures prohibited the wearing of certain red and black Nike basketball shoes by Chicago Bulls player Michael Jordan on or around October 18, 1984.”

The League was about to fine Jordan for wearing those “Devil” shoes. Nike jumped on the moment. They released the famous commercial that put black bars over his shoes. The ominously deep voiceover on the commercial said, “On September 15, Nike created a revolutionary new basketball shoe. On October 18, the NBA threw them out of the game. Fortunately, the NBA can’t stop you from wearing them.”

The fire was lit. The Air Jordan I was a threat to the establishment. They said they were illegal. And that made everybody want them.

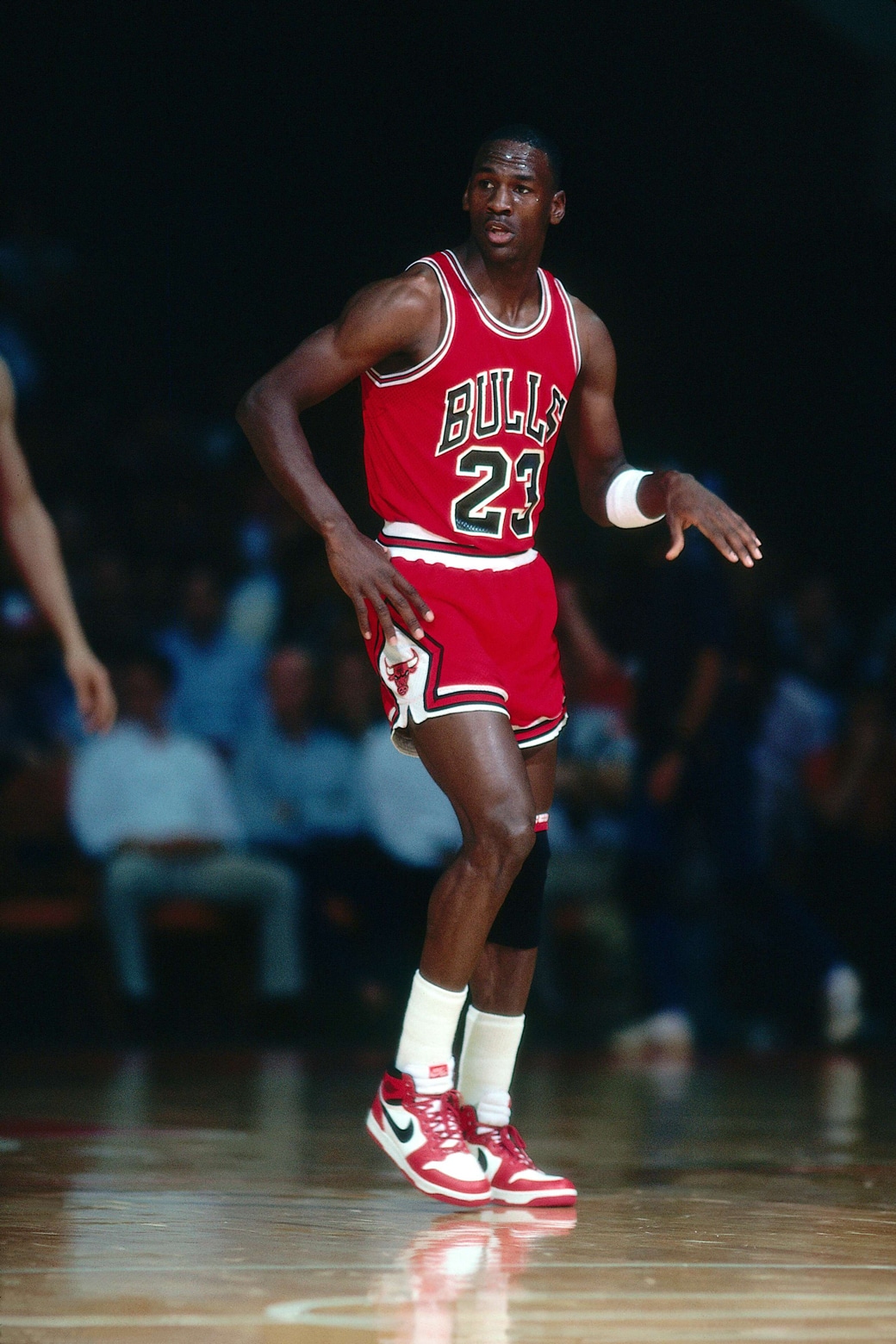

MJ started to hoop in the AJI at the end of 1984, mostly wearing the “Chicago” colorway.

The “Bred” Air Jordan I officially dropped in April of ’85. Red outsole, white midsole, black upper, red collar, red Swoosh and an “Air Jordan” logo.

1985, it arrived. Thirty-three years later, it’s survived.

And then some.

—

GRAB YOUR COPY OF SLAM PRESENTS JORDANS VOL. 4!

Max Resetar is an Associate Editor at SLAM. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

Photos via Getty Images and Nike.